Earlier this year, I met the woman that Ms. McClelland has called both Sybille and K* in her writings.

I met her at a meeting for rape survivors in Port-au-Prince. She is a 25-year-old mother of three children. She has a beautiful singing voice and often sings in talent shows to inspire other rape survivors.

This incredibly brave and talented woman speaks Creole, French and Spanish. She learned Spanish while traveling between Haiti and the Dominican Republic to buy grocery items, toiletries and non-perishables that she would then resell in Port-au-Prince.

She lost the father of her older children to illness before the earthquake and lost the father of her youngest child on January 2010, during the earthquake. She also lost her home, which is how she ended up living in the camp where she was raped.

In her essay, Ms. McClelland writes that K*’s trauma led in part to her own breakdown. Nevertheless, during Ms. McClelland’s ride along with K*, on a visit to a doctor, Ms. McClelland, as has been reported elsewhere, live-tweeted K*’s horrific experiences. The tweets put K*’s life in danger because they identified the displacement camp where K* was living–with details of landmarks added–her specific injury, her real name, and suggest that she is a drug user.

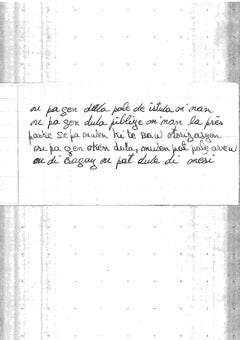

When K* found out about Ms. McClelland’s tweets, even before Ms. McClelland’s original Mother Jones article was published, K* wrote a letter to Ms. McClelland and Mother Jones magazine asking that Ms. McClelland not write about her. Her lawyer emailed the letter to them on November 2, 2010.

The full text of the letter in K*’s own handwriting is attached and is written in Haitian Creole. It says:

You have no right to speak of my story.

You have no right to publish my story in the press

Because I did not give you authorization.

You have no right. I did not speak to you.

You have said things you should not have said.

Thank you

Ms. McClelland has stated on this same twitter account that she had K*’s permission and K*’s mother’s permission to ride along with them, but she certainly–according to K*’s lawyer, and the driver on the ride along, and K* herself–did not have K*’s permission to tweet personal and confidential information about her. And even if Ms. McClelland in some way thought she had K*’s consent, the attached letter should have made it clear that it was withdrawn and that she had, as the letter states, “no right” to write about K* anymore, especially in ways that her previous tweets had made K*’s and her location easily identifiable.

I have K*’s permission to publish this letter and to talk about K* because she is angry at the way Ms. McClelland has portrayed her in the tweets, has ignored the wishes of her letter and continues to make K* part of her story.

This week, K* wrote me an e-mail from Port-au-Prince saying, “I want victims in Haiti to know that they can be strong and stand up for their rights and have a voice. Our choices about when and how our story is told must be respected.”

She closed her note by adding, “Se wozo nou ye,” citing an irrepressible reed which grows in spite of impossible conditions, on the side of Haitian rivers.

“We are wozo,” K* writes. I agree.

Many have applauded Ms. McClelland’s courage, while showing little consideration for K*. However, faced with extraordinary obstacles, to which one should not add other types of exploitation, K* and Haiti’s other rape survivors, have had to be more than courageous. They’ve had to be wozo.

Edwidge Danticat is a Haitian-American writer living in Miami, Florida.