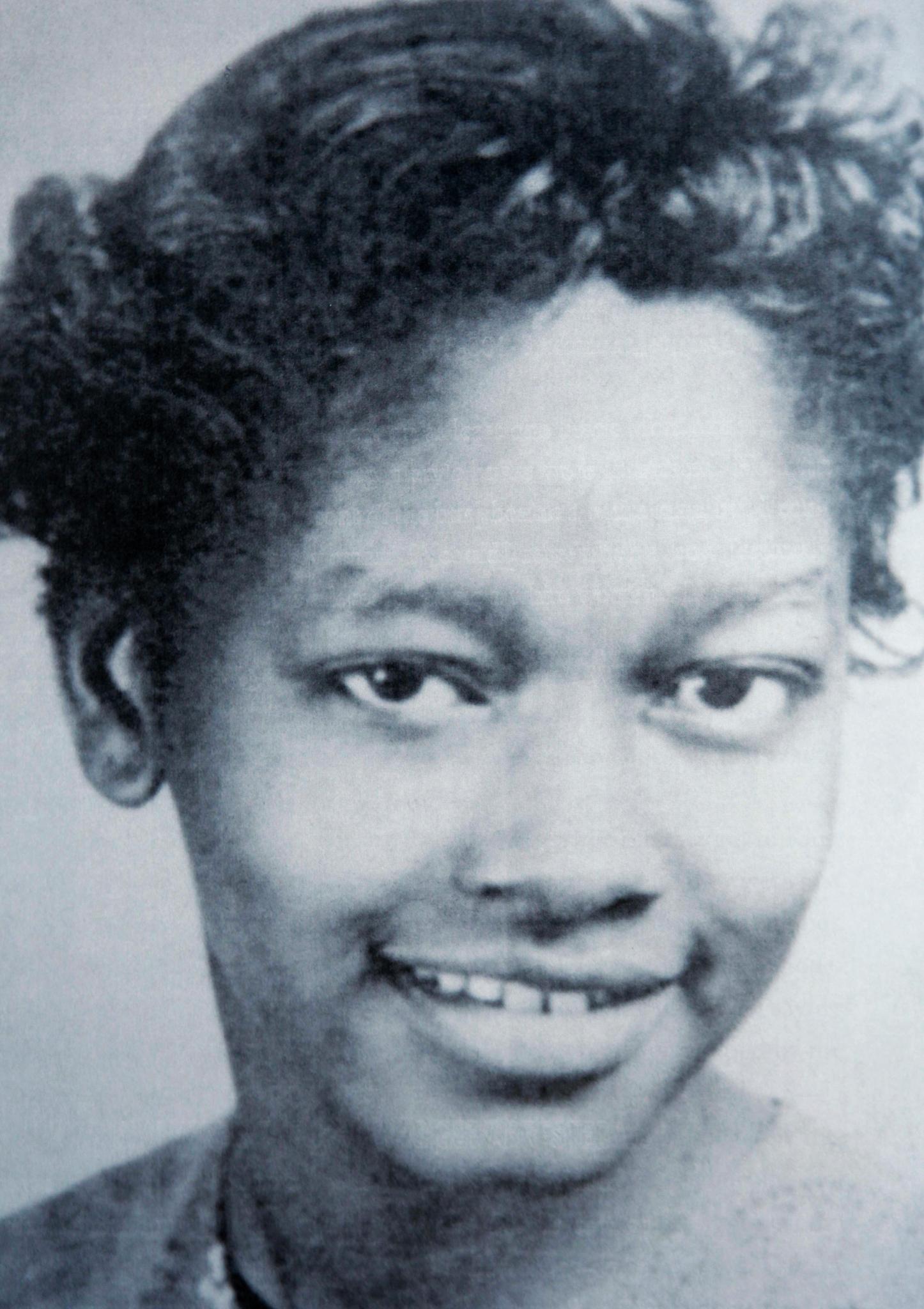

Claudette Colvin, 73

Plaintiff in Browder v. Gayle

Nine months before Rosa Parks made history, Claudette Colvin took her own seat for justice. The teen, who later became a protégée of Parks, helped usher in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. She was one of four plaintiffs in Browder v. Gayle, the landmark case heard by the Supreme Court in 1956, which struck down Alabama’s bus segregation laws.

Wednesday, March 2, 1955, was like any other day in Montgomery, Alabama. I was coming home from Booker T. Washington High School with my classmates, and about 13 of us boarded the bus. We took seats in the rear while the Whites sat in the front. The bus became crowded and the driver asked for a seat because a White woman was standing. Three of my friends moved, but I remained seated. The woman wasn’t elderly. In fact, she was young and looked like an office worker. In my heart I knew it was unfair.

Now, let’s be clear: I wasn’t breaking the Jim Crow laws by sitting in the White area. There were empty seats—two across the aisle and one next to me. The bus driver wanted all four of us to get up so this one White woman could have a seat to herself without being forced to sit near a Colored person.

A few weeks before this, in class we were discussing the national barriers that were being broken down by people like Jackie Robinson. I was intrigued when my teacher talked about the courage of women like Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth. That day on the bus, I felt Harriet on one side holding me down and Sojourner on the other. It was as if I could not move.

The driver didn’t stop, but when we got to Court Square, a traffic policeman came to the back door. I said, “I paid my fare and this is my constitutional right.” The officer told the driver he had no jurisdiction and left. We thought it was over, but someone must have called a squad car because two more policemen quickly showed up. One said, “Gal, why aren’t you giving up your seat?”

I became more defiant saying, “I paid my fare.” They knocked my books out of my lap, grabbed both my arms, dragged me and handcuffed me. I was shouting, “This is my right!”

I stood about 5 feet 2 and wore a size 6, but they manhandled me. They started guessing my bra size and talking about me messing with boys. At the police station someone said, “Put this bitch in Atmore [a female prison].” I was pushed into a holding cell, where I broke down crying. It felt as if my life had suddenly become an old Western movie. You hear that key go clank, and you realize you’re locked in. I started saying the 23rd Psalm.

My friends ran to get my mother. She called our minister and the Montgomery NAACP president E.D. Nixon. He was like the Al Sharpton of those days. I remained in jail for about three hours before someone paid to get me out.

The local papers wrote about the arrest. Later I was tried as a juvenile and put on probation. I was charged with violating segregation law, disorderly conduct, and assault and battery on a policeman, accusing me of scratching the arresting officer, which I didn’t do. The Montgomery Bus Boycott began in December 1955, and by 1956 NAACP leaders came to me and asked me to be part of a lawsuit they wanted to file on my behalf and that of three other women, to challenge segregation on public buses. The attorneys thought that I would not make a good test case because of my age. I know people have said that I was pregnant at the time of my arrest, but I got pregnant after that. Eventually, the case went to the Supreme Court and we were successful.

I couldn’t find a job in Montgomery after that. I was ostracized by my community. I left the South in 1963 and was living in Morristown, New Jersey, when the March on Washington took place, so I watched it on television instead. I’ve always told my children that once they go out into the world, they must have two heads and two minds: one to keep grounded, the other to deal with corporate America. One of my sons passed; the other is a CPA in Atlanta. My grandchildren are doing well: I have a granddaughter who is an R.N., another is in college, and some are in the military. None of them are in the criminal justice system, and that’s a blessing. Although there is still a lot of work to be done, you could say my family did reap the benefits of Dr. King’s dream.

To read more memories from the unsung heroes of the Civil Rights Movement, look out for the October issue of ESSENCE magazine (on stands next month).