Writer and activist Jordyne Blaise examines the role we play in abetting relationship abuse and what we can do to stop it.

It’s been said that you never forget your first time. Not only have I not forgotten my first time investigating an allegation of intimate partner violence, but I’ve also thought about that instance before every survivor interview I’ve conducted since. Getting a young woman to talk about what is likely one of the saddest and most frightening moments of her life requires a special combination of tenderness, objectivity and patience. As an investigator, I aim to get to the truth. As an activist, I want people to understand that no one has the right to anyone else’s body without consent. And as a woman, I yearn to protect. Yet I’ve had to accept that I will not always be able to accomplish all of those objectives.

In 2010, more than one in three women reported experiencing relationship violence and nearly 70 percent of those reporting experienced these behaviors under the age of 25, reveals the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey. African-American women are not only disproportionately affected by relationship violence, we are also more likely to die from it. Homicidal domestic violence is one of the leading causes of death among Black women between the ages of 15 and 35, according to statistics.

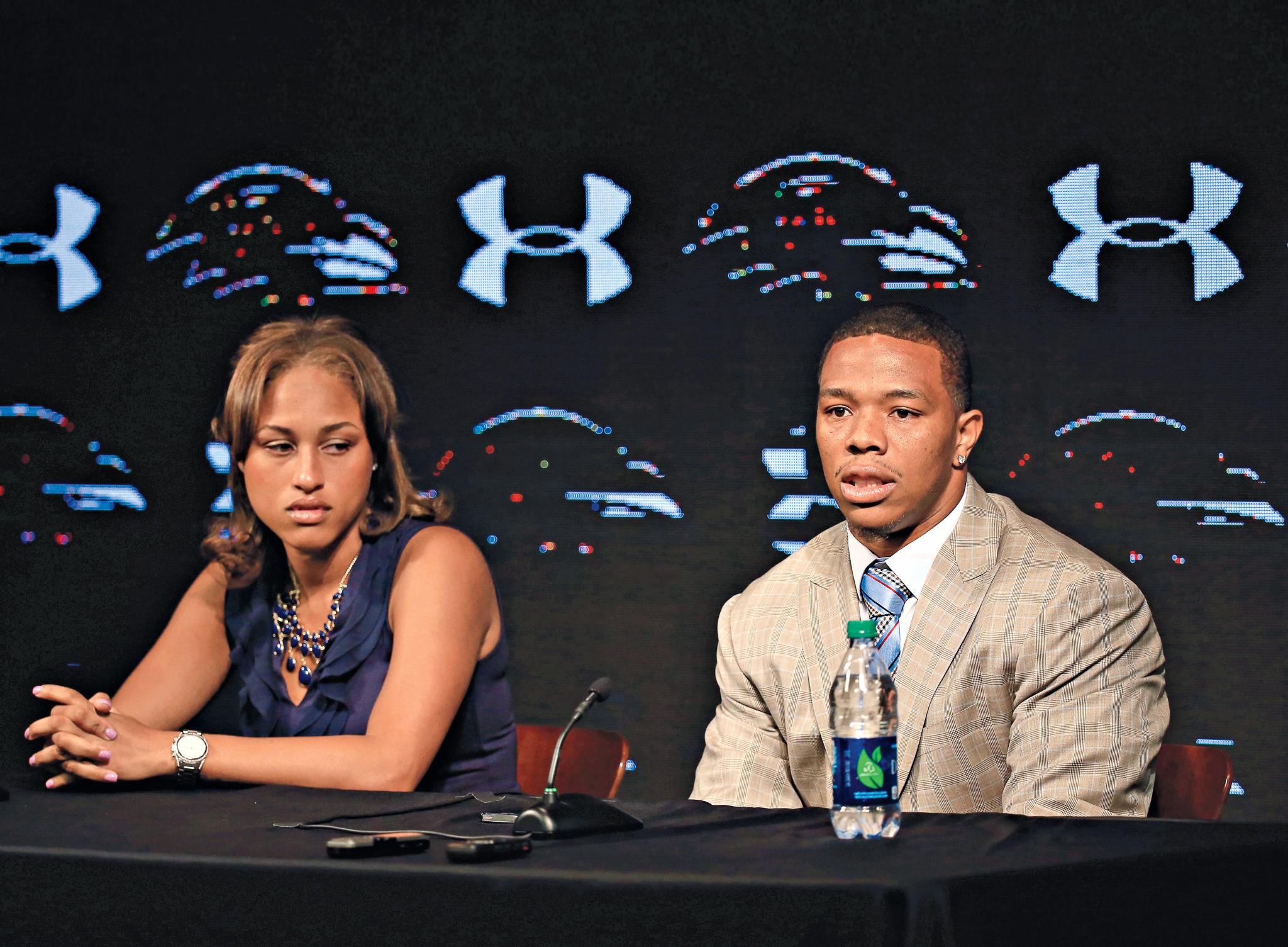

For many Black women, the ability to leave an abusive partner is complicated by the effects of poverty and discrimination, as well as religious and cultural beliefs. These realities are compounded by the fact that nearly half of Black women killed by an intimate partner die while attempting to leave, according to the Institute on Domestic Violence in the African-American Community. What’s more, studies show that Black women are often socialized to forgo their personal well-being for the sake of the family unit. Reporting an abuser can seem like a betrayal, considering the mass incarceration of Black men. It is easy, then, to imagine why Janay Rice longed for privacy after the release of a video showing her being attacked by her then fiancé, now husband, Ray Rice.

As we combat gun violence experienced by Black men, there is a noticeable absence of Black women from discussions about how these issues impact us directly. More than half of Black women killed by an intimate partner are killed by handguns, says the Violence Policy Center. Yet relationship violence is almost never included when gun control is being debated. And while there is an increased focus on targeted services for Black males through initiatives like the White House’s My Brother’s Keeper, the unique needs of Black women often go ignored.

There is undoubtedly a cultural shift taking place in the ways we are addressing sexual assault, stalking and physical attacks by intimate partners. But we have only begun to scratch the surface of how profoundly women are affected by these behaviors. The general public is still more concerned with a victim’s decision to stay than it is with a batterer’s decision to abuse.

In my work enforcing relationship violence policies at North Carolina State University, I’ve learned that the greatest determinants of a woman’s ability to leave an abusive situation are socioeconomic status and access to support systems. Stereotypes about African-American women’s attitudes, sexuality and resilience in the face of adversity can create barriers to accessing help services and cause others to excuse abusive behaviors. We must work to ensure Black women are not left behind.

The simplest way to become a part of the solution is to support survivors. Become a good bystander by intervening when appropriate and safe to do so. Talk openly about sexual violence to create safe spaces for victims to report their experiences. Having culturally competent resources that address the needs of women of various identities can make all the difference in whether a woman can transition successfully out of a violent relationship. For more information, visit ncadv. org. If you need help, call the National Domestic Violence hotline at 800-799-SAFE (7233).

Jordyne Blaise is an attorney and assistant equal opportunity officer at North Carolina State University.

This story was originally published in the December 2014 issue of ESSENCE, on newsstands now.