As I look at the Syrian refugees, spilling out onto European borders, desperate for a safe harbor, and listen to all the US politicians debating whether they’ll allow them into their states, I wonder who they are envisioning as these refugees. Do they see me and my family?

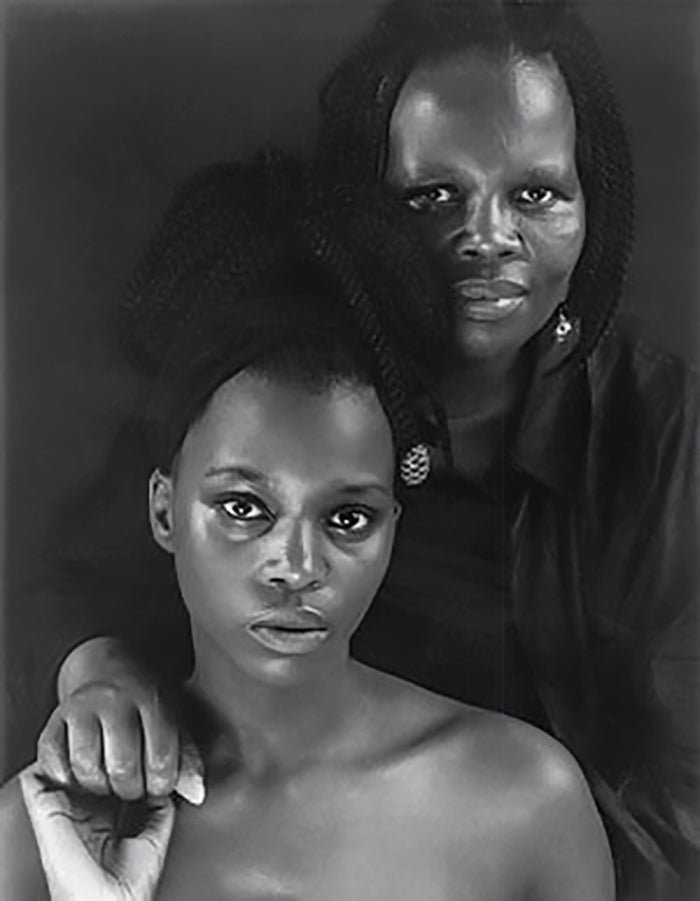

My mother was a political prisoner in South Africa.

She wasn’t as well-known as other political prisoners like Nelson Mandela, or the current South African president, Jacob Zuma, but she was one of the countless African activists whose resistance to the apartheid government was met with imprisonment. She certainly wasn’t a criminal.

I was 9 years old when a group of policemen came banging on the door in the middle of the night, searching for her. They took her to the police headquarters and brought me with her. In later years, I would learn that this was the beginning of the psychological torture often inflicted on prisoners of conscience, because why else would you bring a 9-year-old child into a police station and make her watch as a close confidant—a man I considered an uncle—fingered my mother as the woman the police were searching for.

“Yes, that’s her,” he said somberly.

The police regularly took my mother in for questioning about her political activity. The last time, in December 1986—the time they took me in with her—they held her for six months. It doesn’t seem long when you consider other activists, like Mandela, who were behind bars for most of their adult lives. To a 9-year-old child, those months were an eternity. And yet, we were among the lucky ones because my aunt lived in Harlem and had been petitioning the human rights group Amnesty International to start a letter-writing campaign. People around the world—people we’d never met—wrote impassioned letters to the South African government, pressuring authorities to either charge my mother or release her. It worked.

I remember my mother’s elation, and panic, the days after her release. Joy at being reunited with her family, and anxiety at knowing that the police could be back at her door. It’s the psychological torture many activists often spoke of. Soon after her release, with little more than a few dollars and suitcases of our belongings, my mother and I were on our way to New York City. Amnesty International had helped secure us refugee status in America.

And so, we were refugees.

I’ll never forget the cantankerous immigration officers who treated us like we had the plague because of that stamp: “Refugee.”

“Do you speak English?!” they shouted impatiently.

“Do you have any money?”

In my mother’s passport, which she saved as a keepsake until her death in 2012, it was written “$49.”

We came to America with $49.

On those long immigration lines, my mother, the entrepreneur, the first to graduate from college among her siblings, the hope—was just another refugee, begging for entry. On those lines, lawyers, doctors, mathematicians, scientists, humbled themselves in the face of severe ignorance because they knew this was better than what they were leaving behind back home.

I think about this as I watch the Syrian refugee crisis and listen to politicians call for President Obama to bar them entry. Back when I first came to the U.S., the running thought was that African refugees were bringing AIDS. Today, Syrian refugees are said to be bringing terrorism to our shores. What is fact and what is prejudiced fiction?

I dare not say I have a solution to the crisis because I don’t, but I keep thinking about my own family, and the Syrian families who are going to unbelievable lengths in search of a better life.

I keep thinking about what would have happened had my mother and I not been allowed to come into the United States. She would have most likely gone back to prison. She may have become one of the countless South African activists who simply disappeared. I may have never become the woman I am today: fully African; wholly American.

Yolanda Sangweni is the entertainment editor at ESSENCE.com. Follow her on Twitter.