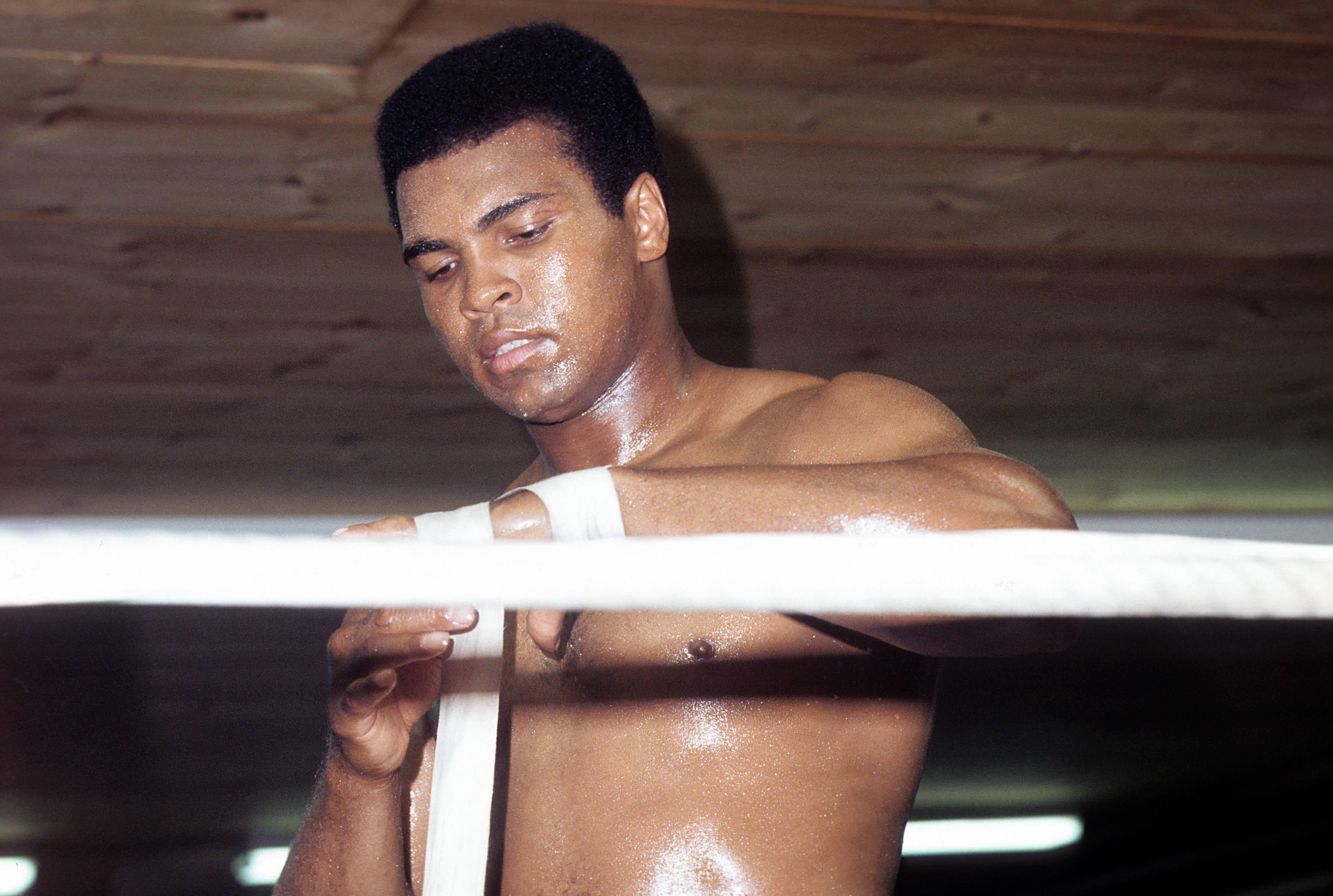

In my first exposure to the late, great (“the greatest,” in fact) Muhammad Ali—a match against upstart heavyweight Leon Spinks in February 1978—he lost his title. I watched the bout live on CBS from the Bronx apartment of my best friend’s family. (I was 7; Ali was 36.) One of the greatest upsets in boxing history, belligerent adults around me were all devastated. It wasn’t until one of my father’s recurring Black Manhood 101 lectures later that week that I fully understood quite why.

12 Inspiring Muhammad Ali Quotes That Will Move You

Relating the Vietnam War to a 7-year-old can’t be easy, but somehow I understood Dad’s explanation of Ali’s conscientious objection when he finally quoted the champ: “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong; no Viet Cong ever called me ‘nigger’.” My father (all of 27 at the time) was a race man himself, and recounted Ali’s biography with great pride. He explained about Cassius Clay’s name change—his Muslim conversion to the Nation of Islam and friendship with Malcolm X, star of the Malcolm X Speaks paperback in our living room. He even touched on Ali’s pan-Africanism, going back to Africa staging a championship fight in Zaire.

Muhammad Ali’s Life in Pictures

Dad conveyed Ali’s characteristic, repeated defiance of White supremacy in broad strokes, but it worked. I spent the rest of the month racing around in my Underoos with “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” on my lips. When a Superman vs. Muhammad Ali special-edition comic dropped that spring (Ali, of course, won), I was a proud owner. Apart from my own father, and a pre-Off the Wall Michael Jackson, Muhammad Ali was my first living black male hero, for all the right reasons.

Everything You Should Know About Parkinson’s Disease Following Muhammad Ali’s Death

In fact, Ali ruined me as a sports fan. His cultural nationalist politics attracted and inspired me at least as much as his rope-a-dope style or his KO combinations. Ali contemporaries like tennis star Arthur Ashe, basketball’s Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and others also clearly held the Black community close at heart. But by the time I traded my Underoos for Air Jordans in the 1980s, the likes of Mike Tyson, Michael Jordan, etc. never seemed to stand for much more than selling sneakers. I lost interest in sports as a result of athletes falling short of the Ali standard.

In September ’78, when ABC televised the live Ali-Spinks rematch, I was fully aware of who I was rooting for and why. And when Muhammad Ali reclaimed his title as heavyweight champion of the world that night, no one cheered louder than this third grader from the Bronx. Upon news of his death this weekend, my 10-year-old son was already familiar with the champ, but my 8-year-old was not. And so through the modern wonders of YouTube, Netflix and Apple TV, it was my pleasure passing down to my own son the legacy of the Greatest of All Time.

Miles Marshall Lewis is a pop culture critic and music journalist. Follow him on Twitter.