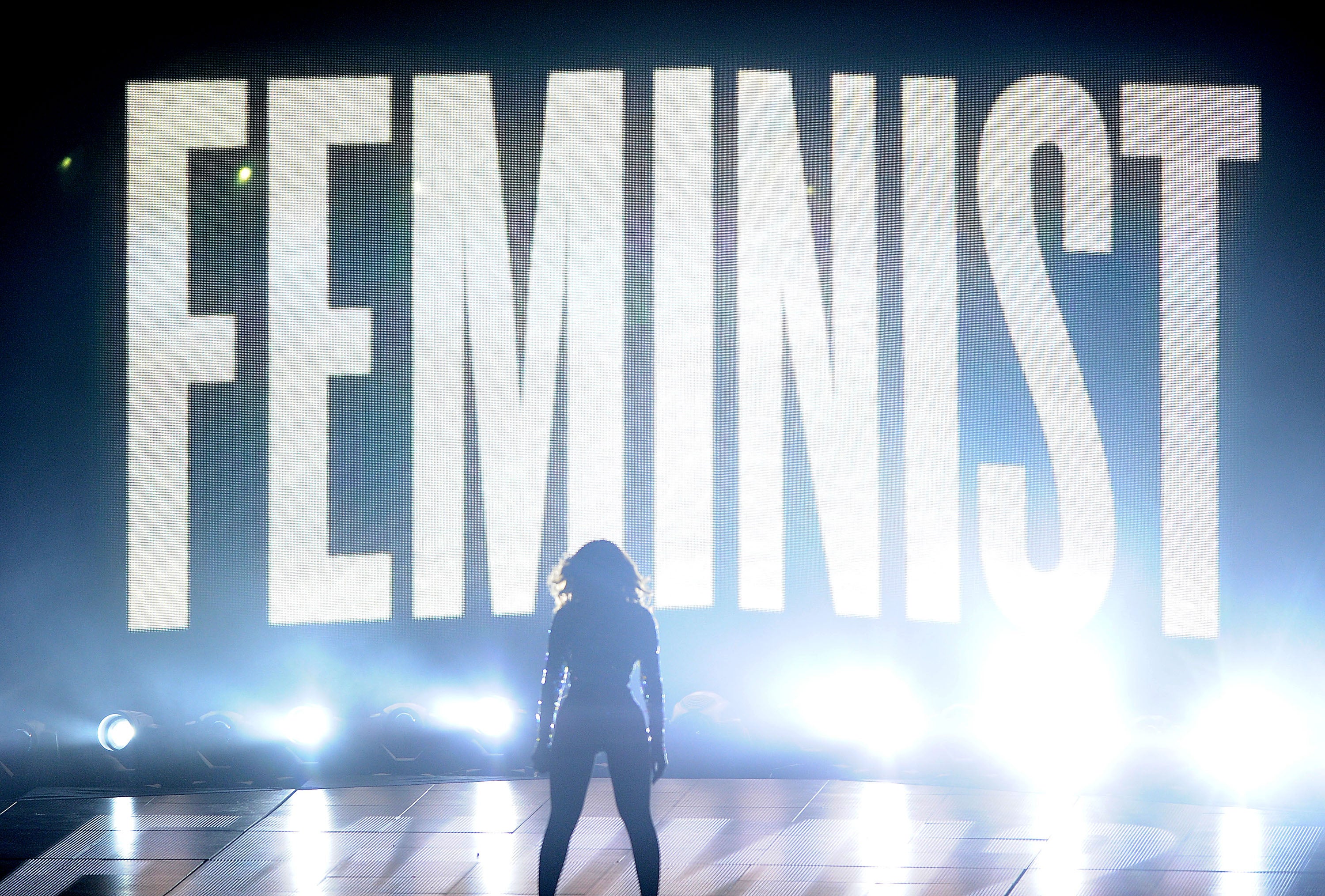

As a Black woman, a Texan, and an admitted pop culture junkie, I am a huge Beyoncé fan. As an avid reader and author, I am also a fan of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, whose tour de force, Americanah, is one of my favorite novels of the past few years. And as a feminist, I, like countless others (including Beyoncé), found Adichie’s TEDx talk, We Should All Be Feminists, inspirational and moving.

So I am disheartened by Adichie’s expressed resentment of her association with Beyoncé after her authorized sampling of her TEDx speech. Her comments strike me as insensitive and inconsistent with the generous spirit and humanity of We Should All Be Feminists.

To be clear, my discomfort does not arise from her dismissal of Beyoncé’s form of feminist expression as “not my style.” Commenters have rushed to defend Adichie’s right to her own form of self-expression, and I don’t disagree. Feminism not only recognizes and defends women’s humanity and human rights, but it embraces their individualism as well.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter for the latest in hair, beauty, style and celebrity news.

My issue with Adichie’s comments is that she didn’t stop there. Though Adichie deigned to acknowledge Beyoncé as “lovely” and gave a nod to her “girl power,” Adichie imposed a borderline elitist value judgment on the way in which Beyoncé – who listened to, supported, and helped spread awareness of Adichie’s art and advocacy – chooses to express her own art and advocacy:

“Her type of feminism is not mine, as it is the kind that, at the same time, gives quite a lot of space to the necessity of men. I think men are lovely, but I don’t think that women should relate everything they do to men…We women should spend about 20 per cent of our time on men, because it’s fun, but otherwise we should also be talking about our own stuff.”

These and other statements Adichie made fail to resonate with me on multiple levels. First, I find them more reminiscent of author Jonathan Franzen’s diss of Oprah than a thoughtful discourse on feminism. Second, they are wholly inconsistent with the message Adichie expresses in We Should All Be Feminists and the themes she explores in Americanah. Third, with their focus on gender (as opposed to gender inequality and sexism), their litmus tests and their lack of empathy, her comments seem to belie the beating heart of feminism.

I’m long in the tooth enough to remember when publishing darling, Jonathan Franzen, declined Oprah’s invitation to be featured as her book club selection on her TV show and criticized her audience and book picks. This was back when a mention by Oprah was the equivalent of a winning lottery ticket. To be fair, he later kissed and made up with Oprah. But at the time, he preferred to remain exalted in the bubble of literary purists than to seize an opportunity to expose his works to a broader audience of regular folks.

Without a gun to her head, Adichie accepted Beyoncé’s request to include excerpts from her speech in “****Flawless.” In her own way, Beyoncé has become the Oprah of the music world, so successfully cultivating her art and her brand that she has become a Harvard Business School case study. Now, I am no MacArthur Fellow like Adichie, but I do have a Harvard Law degree and years of experience as an adviser of artists and businesses, so I’m well-versed in the concept of “reasonable expectations.” And I have a Texan upbringing with a no-nonsense mother and grandmother who regularly challenged my fancy pants with “you’re no fool, what did you expect?”

So Adichie’s claims that “I am a writer and I have been for some time and I refuse to perform in this charade that is now apparently expected of me,” ring naïve at best, and completely disingenuous at worst. Particularly since she expressed no objections to Dior’s splashing “We Should All Be Feminists” on couture t-shirts and using “****Flawless” (and the Adichie excerpt) as background music for its runway show (which Adichie attended).

Adichie touched me in her TEDx speech when she encouraged us all to be angry about sexism because “anger has a long history of bringing about positive change.” Her belief in “the ability of human beings to make and remake themselves for the better” was uplifting. Many of Beyoncé’s recent works articulate deep wellsprings of anger, pain, denial, healing, reinvention, freedom, empowerment, and joy that a broad swath of women can connect with on some level. In the Lemonade album and accompanying film, for example, Beyoncé not only touches upon her emotional response to a relationship, she digs deep within herself and remakes herself in a way that embraces her vulnerabilities, her insecurities, her solidarity with other women, and her connection with her history in a way that begets awareness and activism against broader injustices. The fact that she explores relationships with men in her work does not render her artistic expression invalid.

I understand not wanting to be defined by relationships. But relationships are a fact of life and a huge part of our lives. That is why love has been such a seminal topic of art, literature, and music throughout the ages (cue Shakespeare reference). Love – whether for a lover, a spouse, a parent, a friend, or a passion – invades our lives, our thoughts, our very beings, despite our will or attempts to rationalize it away.

Love is illogical. It gets in the way. It is an unavoidable impediment, and pleasure, of the human condition. In fact, a major plot theme of Americanah is the protagonist’s thwarted relationship with her first love over a span of years, as well as her navigation of other relationships. So it’s paradoxical that Adichie would criticize or set up an arbitrary litmus test for Beyoncé’s use of relationships as a vehicle to explore broader themes of feminism, self-examination, and growth, when she herself won a National Book Award for doing so.

Feminism should expand opportunity and self-expression, not limit them. Feminism should not be a narrow, binary exertion of essentialism. Adichie, however, seems to blur the lines between notions of gender and gender inequality/sexism in her recent comments. And she fails to acknowledge or empathize with the reality of most women’s lives as complex individuals juggling a menagerie of roles, responsibilities, relationships, and desires in life. Most women can’t afford the luxury, nor should we have to segregate any aspect of our life from our overall expression of ourselves to remain true “feminists.” I don’t desire to cut myself up into little pieces in order to avoid “talking about men” more than 20 percent of the time, whatever that means.

Perhaps I defend Beyoncé because I know where she comes from. I was born and raised in that world. I was a nerdier variety of the Texan bougie Black American Princess than Beyoncé, but I am no stranger to the pretty-girl culture she decries in “Pretty Hurts.” Whereas I was pushed into books, Beyoncé was pushed into pageants and performances, defined by her looks and her chops in the same way I was defined by my SAT scores. And despite my good grades and college prospects, I eagerly performed high kicks at halftime and modeled for a local department store. “Perfection is the disease of a nation,” and it is a long journey to grow beyond these external definitions and societal pressures. The fact that Beyoncé has embraced that journey in her work is something I can’t bring myself to disdain.

And perhaps I defend Beyoncé because I believe that empathy is an essential element of feminism. An element Adichie disregards in her criticisms of people who associate her with Beyoncé. Adichie remarked, “Are books really that unimportant to you? Another thing I hated was that I read everywhere: now people finally know her, thanks to Beyoncé, or: she must be very grateful. I found that disappointing.”

I find it disappointing that a woman can challenge others to empathize with the plight of women and “all become feminists,” but lack compassion and empathy for differences among women. I find it disappointing that a self-proclaimed oracle on feminism would intentionally drive wedges and behave in such a small and short-sighted way toward a woman who appears to have treated her with nothing but generosity and respect. I find it disappointing that such a remarkable woman would allow self-righteousness to blind her to the power and beauty of connections, and grace, among women.

Beyoncé’s brand of feminism may be blonde and bootylicious. But it is generous. And it is empathetic. And it is inclusive of other women’s circumstances and differences.

That’s why Beyoncé is my type of feminist.

Ginger McKnight-Chavers, author of In the Heart of Texas