To understand the driving force behind today’s current Black liberation movement, to recognize the historic pattern and large scope of state violence against communities of color, to dissect the most recent wave of white nationalism surging through the nation is to know the duality of African-American life presented by W.E.B Du Bois in The Souls of Black Folk.

Hailed as the bedrock of any examination on Blackness in America — from literature to front-line resistance — the century-old exploration of “the color line” stands unblemished by time, its wholeness applying fully to the era of Barack Obama, Black Lives Matter and Donald Trump.

Presented by Restless Classics, with a pointed introduction by journalist Vann R. Newkirk II, the newest edition of Du Bois’ work presents itself through the lens of today’s political and social climate, highlighting the ugly truth that white supremacy’s roots still grip America and serving as an introduction to a generation fighting a familiar battle for liberation, one that our elders have already witnessed.

With a release date of Feb. 14, the new edition also features original illustrations from Steve Prince, who “brought alive with images the very matters of spirituality and music that Du Bois engages with in this book,” Restless writes.

Just in time for Black History Month, ESSENCE, along with Restless Books, presents Newkirk’s entire introduction, which examines the immortality of what can be considered the most important piece of literature to date.

You can preorder your copy of Restless Classics’ The Souls Of Black Folk here.

________________________________________________________________________________________

THE SOULS OF BLACK FOLK

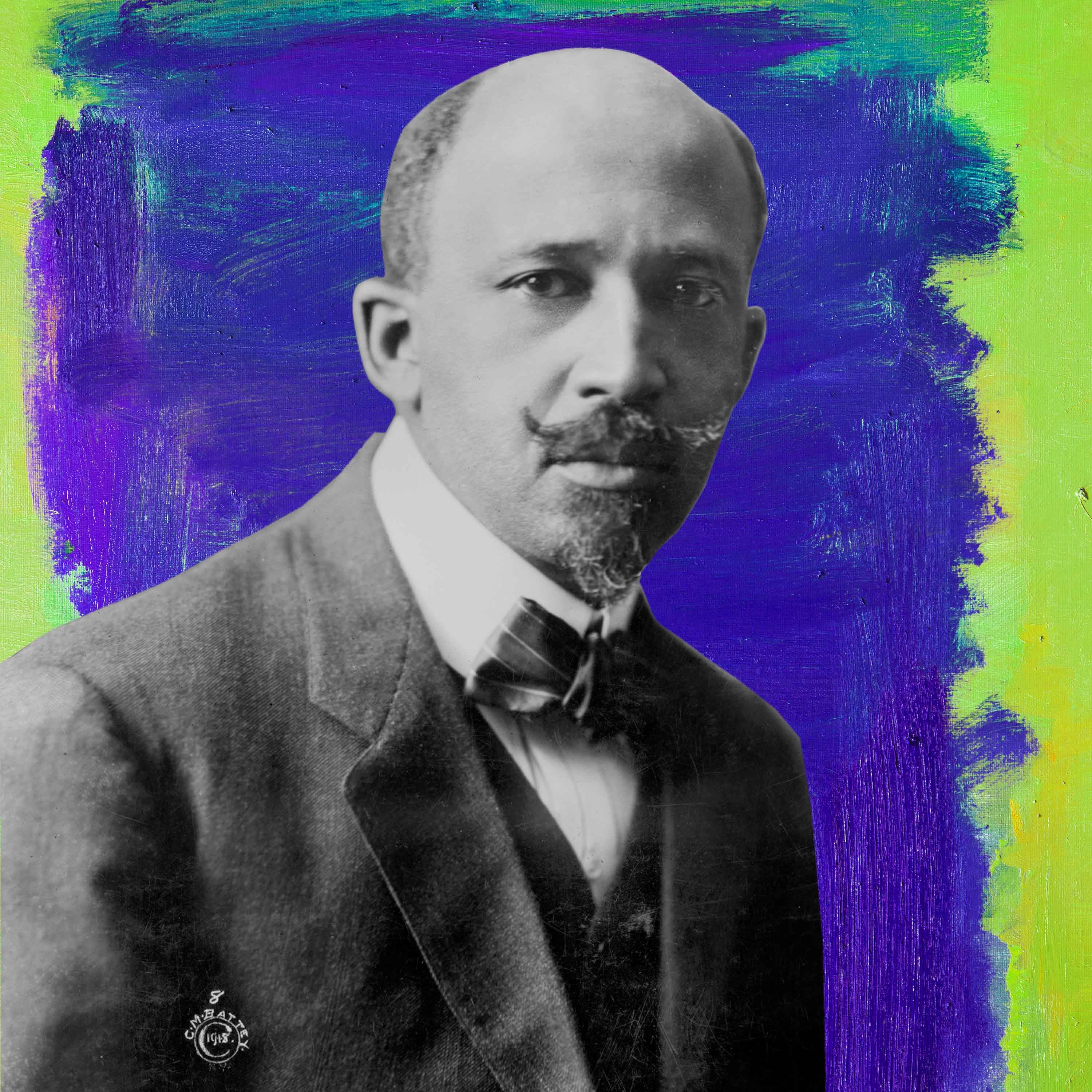

W.E.B. Du Bois

Introduction by Vann R. Newkirk II Illustrations by Steve Prince

“The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.” So William Edward Burghardt Du Bois—pronounced as he did in a manner that rhymes with “new toys”—outlines the concern of his 1903 collection of essays.

Though Du Bois was a man of prodigious skill, who in the course of his life mastered disciplines as diverse as fiction and sociology, he never claimed a talent for prophecy. Still, the “color line” of which he wrote would go on to dominate not only the policies, economics, movements, and social developments of the twentieth century, but so far this little sliver of the twenty-first as well.

From Barack Obama’s presidency to the rise of Black Lives Matter to Donald Trump’s election amid a furor over voting rights, white nationalism, and racism, the color line is still the country’s core subject, over a century after the first edition of The Souls of Black Folk was published. He made the prescient decision to title the introduction, in which he so succinctly describes the American animus, “The Forethought.”

Subscribe to our daily newsletter for the latest in hair, beauty, style and celebrity news.

The Souls of Black Folk has been perhaps the most influential work about race in America in the 113 years since its release, and I hardly go a day without thinking about it. My first time reading it was in a freshman literature class at Morehouse College, and I recall furious highlighting, dog-earing, and margin-scribbling as I pored over words that for the first time finally came close to explaining what I felt about my blackness. Du Bois’s description of a “veil” separating my world from the world of mainstream America was maybe the first prompt for me to sit down and examine the microaggressions and frustrations that I did not have the language to understand. The ever-present tension in my life was the result of a double consciousness: of course!

As a double major in biology and philosophy—one for my parents’ and community’s sense of my path toward becoming a doctor, and the other for my own personal edification—I felt the echoes of Du Bois’s famous intellectual duel with Booker T. Washington over the course of black America. The necessity of my enrollment at my alma mater, a historically black college (HBCU), became crystallized in Du Bois’s passionate defense of such institutions.

Through his combination of reporting, commentary, cultural analysis, and history, I realized that my own intellectual development needed not be limited by genre or discipline. And thus I count The Souls of Black Folk as the work that has most influenced my career, which has taken me to the very same Atlantic in which Du Bois first published parts of that work. I still have that freshman-year copy, dog-eared, stained, and crumbling, with the margins so full of notes and the pages so saturated with highlighter that the annotations cease to have meaning. But written all over that book in smudges, black and blue and pink, green, and yellow, is one experience that I cannot forget: epiphany.

That epiphany unfolds today. As America faces the demons of brutality and extrajudicial killing, as it is possessed by the ghosts of white supremacy and ethnonationalism, as voting rights for black people continue to be assailed by the state, and as the equality and desegregation gains of the Civil Rights Movement suddenly seem fragile and rather reversible, it is obvious that while Du Bois now rests, his most-famous work does not.

The first note about The Souls of Black Folk is its unusual structure. Collections of topical essays are not uncommon arrangements for books—and Du Bois’s work kicked off a strong tradition in the same vein of race writing—but The Souls of Black Folk shifts through genre, praxis, and voice even as its focus on the problem of the color line remains intense and unmoving. The fourteen chapters are standalone works, many published beforehand, but still connected at the spine by Du Bois’s themes.

With carefully collected epigraphs and musical scores that precede each section, these chapters are transfigured into a panorama, a look at the same fundamental questions through multiple lenses.

The first lens is perhaps the most popular. “Of Our Spiritual Strivings” is one of the most-often-quoted pieces of the black canon, and it is one of the first thorough attempts at understanding blackness through a psychological and philosophical lens.

Du Bois takes a few different paths to answering the question at the heart of this essay: What does it mean to be black? First, Du Bois bounces back a rhetorical question: “How does it feel to be a problem?” he asks. Then, he expands on that question with a touch of mysticism in describing the Negro race as “a sort of seventh son, born with a veil.” That “veil,” as Du Bois describes it, is an ever-present awareness of one’s own otherness.

In the keystone paragraph of the entire volume, Du Bois elucidates a “double consciousness” by which black people seeking to get by in a white world have to dissociate their inner black selves from a performative version meant for white consumption. “One ever feels his twoness,” Du Bois writes, “an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” Deeper into the chapter, the author writes what reveals itself as an outline for the rest of the book.

“Of the Dawn of Freedom,” an essay on the history of the post-Civil War Freedmen’s Bureau finds Du Bois as an activist-historian, his firsthand observation meshing with his Northern detachment. As an introductory text to the era, it is a necessary work. In finding the effort of Reconstruction at fault, Du Bois subverts the common view among many historians of the era that Reconstruction was destined to fail because of deficiencies among black people and of the cause itself.

He describes how the enduring system of racism continued to control nearly everything even half a century after slavery, an idea he develops in subsequent essays. Throughout the rest of The Souls of Black Folk, the political and social forces that contributed to the failure of Reconstruction are in essence an invisible antagonist. Especially today, in the midst of a racial backlash that appears similar in character to the “Redemption” that followed Reconstruction, the lessons of the failure of the era resound.

Du Bois’s famous—or infamous—critique of fellow black political and race-theory leader Booker T. Washington is the third essay in sequence. The dispute between the two men, caricatured as a war between a liberal-arts-minded radical upstart with goals of forcing America to confront racism with reparations, and an appeasement-minded apologist with the goal of cajoling black people into practical submission, is often remembered as acrimonious, and not incorrectly. However, one notes that the start of this rivalry, as officially announced in The Souls of Black Folk, reads more like a student respectfully reproaching an old teacher. Du Bois knew Washington well, and understood the experiential and regional differences that necessarily made him de-emphasize the pursuit of civil rights and integration for black people. This essay, together with the next three sections, forms a semicoherent suite of work in a multifaceted format: criticism of Washingtonian ideals of the black South supplemented with gripping personal experience and reporting. Du Bois rejects Washington’s industrialist vision of segregated prosperity as a way of “shift[ing] the burden of the Negro problem to the Negro’s shoulders.”

That critique continues, by way of example, in the fourth essay, “Of the Meaning of Progress,” which has always been one of my favorite pieces of this book. Du Bois tells the story of his life as a young teacher in a small town, where he became attached to a black community that still struggled to find its way through destitution and marginalization in a changing world.

His students are only tenuously connected to school, and education and contemplation are often cast aside for even the brightest, like the tragic Josie, one of Du Bois’s pupils. As the town becomes increasingly afflicted by criminality, vicious inequality, and industrial exploitation, Du Bois—with a touch of ivory-tower condescension—highlights the mean cycles of their lives. The moving account is probably meant as a dig toward Washington and the kinds of lives Du Bois believes are the end results of his philosophy. Without civil-rights protections, liberal education, and an inward focus on liberation, these Washingtonian yeomen are doomed despite their Herculean work, so goes Du Bois’s implicit argument.

The thread of a coherent anti-Washingtonian view continues in “Of the Wings of Atalanta,” in which Du Bois levies criticism against the materialism of the New South and its reflection in black culture. He lauds the rise of liberal-arts historically black colleges as a way to move the race beyond obsession with materialist concerns and toward the pursuit of humanity. The following, “Of the Training of Black Men,” continues in a more pedagogical critique of Washington and completes the arc of Du Bois’s push for a liberal-arts secondary- and higher-education system as a necessary remedy for the ills of racism.

“No secure civilization can be built in the South with the Negro as an ignorant, turbulent proletariat,” Du Bois says, both purposefully undermining the security for whites that Washington’s vision promoted, and foreshadowing his own midlife turn to Marxism. In that essay can also be seen the seeds of the “Talented Tenth” idea of an elite Negro intelligentsia that would become so associated with Du Bois throughout his lifetime.

The next tetrad in The Souls of Black Folk is often the most-overlooked segment of the book, sandwiched as it is between preceding sections that contain some of Du Bois’s most quoted and known ideas and a set of beautiful experimental essays closing the book. But taken as a whole, the sociological work presented in “Of the Black Belt,” “Of the Quest for the Golden Fleece,” “Of the Sons of Master and Man,” and “Of the Faith of the Fathers” takes stock of Du Bois’s present and provides an early, sober view of nascent free black culture in the South.

Du Bois explores the lands where brutal chattel slavery drove profits under King Cotton, and where a new system akin to it arose almost instantly out of the ashes of Reconstruction. In the first two works of this tetrad, Du Bois travels the breadth of the South and lands in Dougherty County, Georgia, where he surveys the debt-driven tenant-farming and sharecropping system that maintained racial hierarchies. In this analysis, we see how the failure of the Freedmen’s Bureau, recounted earlier, finally manifests as a near-permanent regime of economic inequality.

In “Of the Sons of Master and Man,” Du Bois attempts a feat that feels eerily contemporary: tracing the relationships between segregation and inequality, crime and criminalization, and exposing the broad disenfranchising effort at the heart of Jim Crow. “It is usually possible to draw in nearly every Southern community a physical color-line on the map,” he observes, noting a trend toward segregation and housing discrimination that continues to influence policy and spark riots today. In perhaps the most-chilling connection to the current political and racial moment, Du Bois details the foundation of policing as one not of law and order, but of control of black bodies.

“The police system of the South was originally designed to keep track of all Negroes, not simply criminals,” Du Bois writes. “Thus grew up a double system of justice, which erred on the white side by undue leniency… and erred on the black side by undue severity, injustice, and lack of discrimination.” Thus our luminary author becomes one of the earliest commentators to note the racist origins of the most basic pieces of our criminal-justice system and observe the rise of mass incarceration even as it rose. His account of the institution of the black Church and the role of spirituality and liberation theology in “Of the Faith of the Fathers,” seems a natural counterpoint to the despair that comes from experience with such oppression.

The last four essays in The Souls of Black Folk are, in my reckoning, the most beautiful writing that Du Bois produced, and constitute the emotional heart of the book. Here, the veneer of Du Bois as a measured, journalistic observer is peeled back to reveal the man underneath, and the resulting work is a set of deeply personal and exploratory chapters. “Of the Passing of the First-Born” is a tragic and sorrowful ode to a lost infant son, a eulogy that Du Bois transforms into a fiery howl against the world. “Not dead, not dead, but escaped; not bound, but free,” he writes about his son’s escape from the racism of the world and the “veil” that he confronted as a writer every day. “No bitter meanness now shall sicken his baby heart till it die a living death.”

The psychic cost for Du Bois, standing watch against the evils of racism and for his vigilance against lynching, is suddenly laid bare: what lies underneath in this mourning piece is the man’s raw, damaged soul. Just as for black writers today who catalogue death after death of black people at the hands of police, Du Bois’s work is both catharsis and torture.

“Of Alexander Crummell” is a brief biography that intersects with the previous essay as a sort of character study in the kind of desolation that comes with race work. The eponymous man is a mentor and ideological predecessor to Du Bois, and Du Bois’s own story is reflected in much of Crummell’s life. A northern black man born free in New York in 1819, Crummell became a trailblazer in both the theological and the educational worlds, but was met at every turn with prejudice and obstruction. His dream of Pan-Africanism and of using religion to organize black resistance never quite materialized, but Du Bois stresses how he never succumbed to the despair and depression that should so naturally follow from being both a witness to and a crusader against racism. In the closing, Du Bois writes about his motive to tell Crummell’s story: as a fight against erasure and the prioritization of white history at the expense of the richness of black history.

The penultimate chapter of The Souls of Black Folk is a short story, a form that seems like a departure for both the book and for Du Bois’s analytical demeanor, but actually works seamlessly within both. The author took an interest in fiction—specifically speculative fiction and science fiction—and dabbled in using short stories as a vehicle to probe the corners of his developing philosophies and sociological conclusions.

“Of the Coming of John” is such a work, and tackles the latent and developing “veil” between the two titular Johns, one black and one white. Both characters seek education, though black John’s life is fraught with missteps and setbacks, and he embodies the “work twice as hard” maxim still told to black children. The two still establish similar orbits, but eventually the cracks in black John’s life widen into fissures. A school he establishes is shuttered after he attempts to teach students about race and racism. White John, however, lives a life of relative ease, idleness, and privilege, and eventually sexually assaults black John’s sister. The tragedy of black John’s life finally unravels when he kills white John and faces a lynch mob. The dance of privilege, racial disparities, sexual assault, and lynching that black John and black John’s family face is no doubt a stand-in for what Du Bois saw as the struggle for all black Americans.

Finally, “Of the Sorrow Songs” closes the work by coalescing the running references to Negro spirituals in the introductions of several previous chapters. On the surface, this chapter is a defense of the spiritual as an essential distillation of the Negro condition, and worthy on its own as both a complex high art and a quintessentially American art. But this essay is also about the creators of that art: taking on fully the role of activist, Du Bois launches an angry and forceful defense of black people and black culture and offers a full-throated call for the recognition of black personhood. After a series of pieces that rely mostly on steady, sober journalism, theorizing, and academic writing, “Of the Sorrow Songs” has the sense of the passionate sermonizing that has been common in black literature and speeches on race. Du Bois ends The Souls of Black Folk with a sincere hope that racism and the color line that he had so thoroughly examined could be—with more efforts like his, undoubtedly—eradicated soon. This hope, we know now, would prove to be premature.

In the following pages unfolds one of the foundational texts of understanding the persistent concepts of race and racism in this grand experiment of America—and thus of understanding America itself. Du Bois’s wisdom on race theory does not always transmit cleanly across the ages. Namely, his crude and chauvinistic descriptions of women, his genteel elitism, and his theory of black leadership feel at odds and out of touch with a current black political moment that embraces feminism, womanism, queer theory, a populist anticapitalist ethos, and decentralized leadership. But this book’s incompleteness as an exact framework for understanding race and movement today makes it all the more of a compelling and necessary read, and understanding what it lacks highlights the layers of nuance and thought that have been added to its tradition in the century since its publication.

Anyone who writes about blackness in America owes a debt to The Souls of Black Folk, and contributes to this accretion over the mother-of-pearl it provides. James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time is concerned with the same problem of the color line, and builds on Du Bois’s investigation of the results of racism, at both psychological and sociological levels. In the situation of “the Bottom” neighborhood and examination of the insidious effects of racism, Toni Morrison’s Sula is an extrapolation from Du Bois’s theorizing about the veil and his fictional exploration of it in “Of the Coming of John.” Even today, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me carries with it some of the DNA of Du Bois’s essays and replays some of the fire and anguish of his musings about his own child and the veil. In my field of journalism, the thread between Reconstruction, the history of racism, and the unstable ground of free blackness in America are necessary starting points for any reporting or commentary on race.

Across all genres and media, the idea of the “double consciousness” is almost considered a priori. The demands of the Black Lives Matter movement and the rejection of respectability politics in much of current black art and cultural criticism are animated by the understanding that double-consciousness is a traumatic psychic burden. The importance of hip-hop and defending it as a legitimate reaction to that burden were predicted by Du Bois’s passionate defense of Negro spirituals. Activists today seek to challenge the delegitimization of blackness and black culture that even makes such a double consciousness exist, and by which whiteness enforces itself as the norm by code-switching, apologia, and shame.

Activism also examines the root causes of the problems that still plague black people and asks if the institutions and systems of America can ever truly serve its darker children when, as follows from Du Bois’s analysis, they were originally designed to disenfranchise and marginalize them. Thus, The Souls of Black Folk is also a primer for any young activist or thinker who simply seeks validation in their own interests, character, culture, and questions, or any nonblack person seeking better understanding of a veil that can only be truly known with experience.

Even years later, this book stands as a titanic work of immense foresight and insight. For all audiences—black or not, American or not, academic or activist or adolescent reader—this work should be part of the bedrock of an education on America and its culture. With that bedrock, things will become clearer. On the whole, from the account of the collapse of Reconstruction to the account of the rise of mass incarceration to a critical defense of black music and the story of black John, The Souls of Black Folk is vital in understanding the time-honored question as asked by race theorists and famous soul singers alike, decades since its publication: What’s going on? Unfortunately for us and for Du Bois, the answers for us today and the answers for him in 1903 are all too similar.

Vann R. Newkirk II is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where he covers politics and policy. Vann is also a co-founder of and contributing editor for Seven Scribes, a website and community dedicated to promoting young writers and artists of color. In his work, Vann has covered health policy and civil rights, voting rights in Virginia, environmental justice, and the confluence of race and class in American politics throughout history, and the evolution of black identity. He is also an aspiring science-fiction writer, butterfly lover, gardener, gamer, and amateur astrophysicist. Vann lives in Hyattsville, MD with his wife Kerone.

Steve Prince is an artist, educator, and art evangelist. He is a native of New Orleans, and the rhythms of the city’s art, music, and religion pulsate through his work. Steve’s favorite medium is linoleum cut printmaking. Through his complex compositions and rich visual vocabulary, Steve creates powerful narrative images that express his unique vision founded in hope, faith, and creativity.