Editor’s note: The following account is solely attributed to Nailah Winkfield, mother of Jahi McMath, and other members of Jahi’s family. Children’s Hospital & Research Center could not respond to our specific requests for comment as it did not have permission from Winkfield to discuss Jahi’s medical case in accordance with HIPAA privacy laws.

On December 9, 2013, 13-year-old Jahi McMath was admitted to Children’s Hospital & Research Center in Oakland (CHO) to have a tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Two days later, she was declared brain-dead. Her family was given a couple of days to say their good-byes and to make funeral arrangements. What happened during those days—between that first incision and the doctor’s verdict: “We lost Jahi”—is the subject of dispute between a hospital, whose comprehensive state evaluation found “no deficiencies of quality of care,” and a mother who experienced an unbearable tragedy compounded by what she considers to be callous medical bureaucracy.

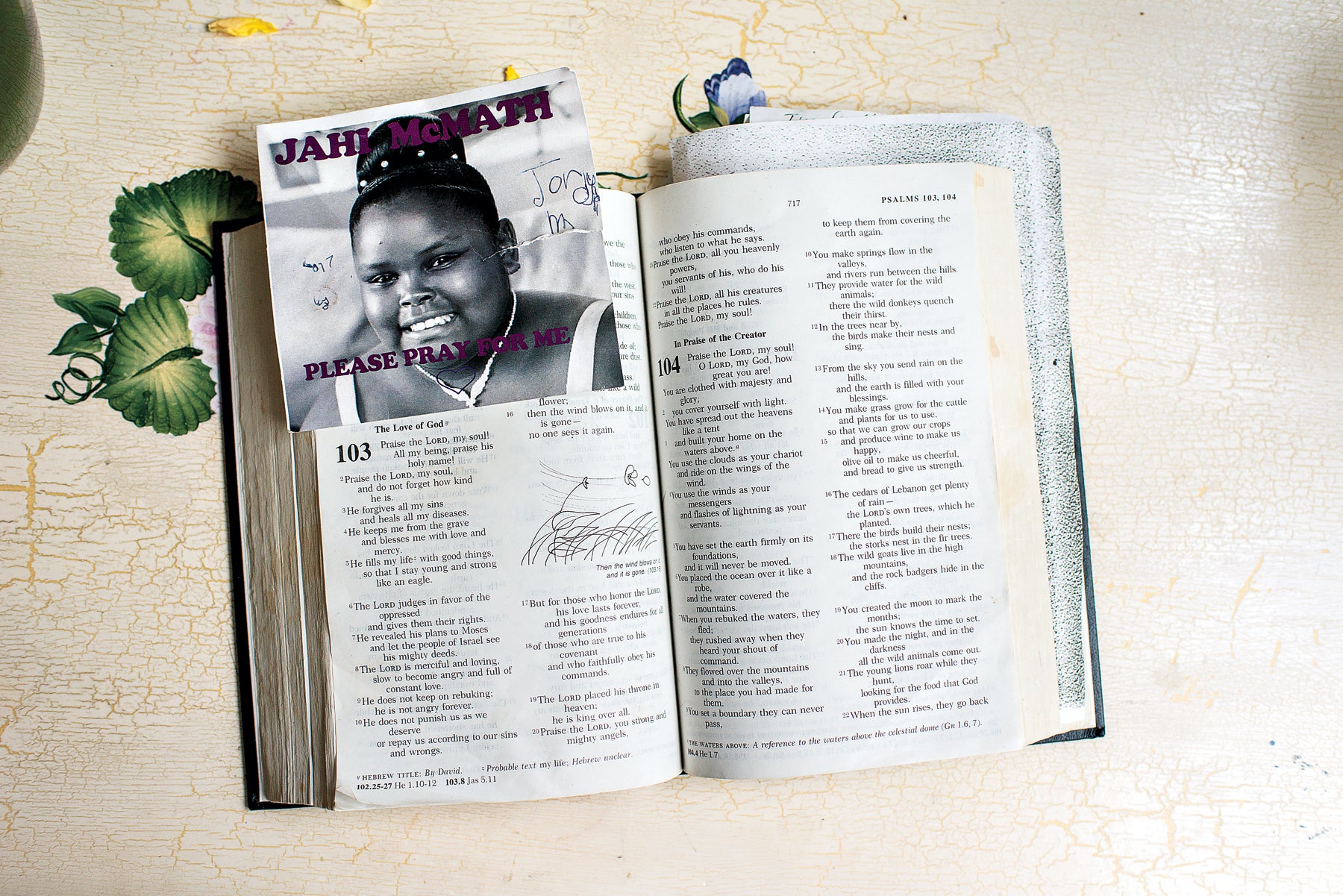

At the center of the conflict is a playful, happy girl known for wearing a smile so fixed that not even her mother’s occasional scoldings could get her to relinquish it. The second of four children, Jahi often helped get her younger siblings ready for school each morning, and preferred inviting her friends over instead of being away from home. Her easygoing sweetness set her apart from her feistier siblings, who have seen their sister just once in the seven months since her surgery.

“Am I okay?” Hours after the procedure, Jahi was skittish Finding it difficult to speak, she had scribbled the question on a sheet of paper and given it to her mother. “Jahi was worried about the surgery,” recalls Winkfield, 34. “She cried all the way to the hospital because she was scared she wouldn’t wake up after.” Winkfield had spent weeks reassuring Jahi that the tonsillectomy was routine and there was nothing to worry about. According to Winkfield, Frederick Rosen, M.D., the operating surgeon, recommended the surgery to treat Jahi’s sleep apnea, which was caused by enlarged tonsils that made it difficult for her to breathe and swallow. Nervous and skeptical, Jahi urged her mother to get a second opinion. “[A high-ranking doctor] agreed with Dr. Rosen’s diagnosis and said surgery would help her swallow better. We brought her there to improve her quality of life,” says Winkfield.

They’d been told by Jahi’s doctors to expect a little bleeding and lingering pain after the surgery. The nurse in Jahi’s room echoed the doctors’ advice that some blood after the operation was normal. Jahi remained communicative, asking for a Popsicle, and then jotting down another unsettling question: “Should I be bleeding this much?” Winkfield continued to placate her daughter, though she, too, began to wonder if that much bleeding was normal.

Later that evening, after spending time talking with family members who’d come to the hospital, Winkfield returned to Jahi’s room, but was turned away. “I was told by a nurse to come back in ten minutes. When I returned, I was then told to come back in another 15 minutes,” Winkfield says. When she was finally allowed to see her daughter, Winkfield noticed that Jahi continued to bleed from her mouth and nose. Over the next few hours, she protested to anyone who would listen that her daughter’s condition couldn’t be normal, but she says her concerns were dismissed by the nursing staff. Because of his growing frustration and insistence that someone take another look into Jahi’s state, her stepdad, Marvin Winkfield, was asked to leave the room.

Jahi’s grandmother, Sandra Chatman, is a nurse with 30 years’ experience. Upon returning to the hospital that night to check in on Jahi, she flew into a panic when she noticed that the teen’s oxygen level was at 79 percent, yelling, “Everybody get in here. Jahi needs an airway!” Jahi’s vital signs were diminishing rapidly. Chatman’s call set in motion a flurry of activity—a medical team rushed in and feverishly tried to resuscitate Jahi. The image was so upsetting to Winkfield that she passed out, was given a sedative and was then admitted to a room in the same hospital where her daughter was now fighting for her life.

After Winkfield came to, a doctor told her that Jahi had suffered brain swelling and had a heart attack. Later, she was pronounced brain-dead. “To this day no one has been able to tell me what went wrong with the tonsillectomy,” Winkfield says.

Brain-dead patients are commonly removed from life support within a few days of diagnosis. The hospital released a statement saying, “Once death is pronounced and is validated by multiple physicians and well-established tests, as outlined in the law, and a reasonable period has been provided to the family, the hospital no longer preserves artificial respiration and circulation.” But Jahi’s family, shocked at the sudden turn of events and distrustful of the medical team that had performed the disastrous tonsillectomy, refused to accept the declaration. To the physicians at CHO, Jahi was clinically brain-dead, and her sporadic physical responses—twitches of the arms, hands and feet—were meaningless spinal reflexes. To Jahi’s family, the movements pointed to a child stranded in some unmapped terrain of the mind, fighting to find her way back to consciousness. The hospital considered it unethical to keep a deceased person on life support. Jahi’s family thought it unconscionable to give up on her as long as there was even a sliver of hope.

This dispute wasn’t just some abstract disagreement about what constitutes life and death—the stakes were high. The two parties became embroiled in a bitter battle, and the negative tone of their exchanges escalated. Winkfield recalls one instance where, in a discussion with the chief of pediatrics, David Durand, M.D., he pounded his fist on a table yelling, “She’s dead, dead, dead!” (A hospital representative confirms that the word “dead” was used in the conversation between Winkfield and Durand, but denies that it was used repeatedly in this sequence.) The conversations that followed were characterized by Winkfield as hostile condescension from highly educated physicians who assumed that Jahi’s family simply didn’t grasp the implications of brain death. And in a medical arena where doctors’ opinions often carry unquestioned authority, Winkfield believes that her steadfast refusal to subscribe to their views was a major point of contention.

Winkfield asked her brother, Omari Sealey, 27, to make sure that Jahi was not removed from life support. “I promised not to let that happen,” says Sealey. He’d taken to sleeping in his niece’s room to monitor her care. In the middle of one sleepless night, Sealey began e-mailing news stations about his family’s battle to keep his niece on life support. The ensuing wave of national media attention thrust Jahi and her relatives into the spotlight, drawing supporters and detractors alike. The hospital maintained its position that a general medical investigation, one that did not specifically probe Jahi’s case, found no evidence of wrongdoing and that Jahi was legally dead. The girl’s family remained undaunted, and rallied support from local clergy and community figures. Jahi’s father, Milton McMath, among others, formed a permanent vigil, logging day after day in the hospital as both a show of support and to preclude the termination of life support. Christopher Dolan, an attorney, learned about the situation and took on the family’s case pro bono. He filed a series of requests in state and federal court for temporary restraining orders that sought to bar the hospital from removing Jahi from the ventilator. The orders bought Jahi some time, but the hospital was not required to provide her with a feeding tube. For 25 days, until the family was able to transfer her to a new facility, Winkfield was unable to provide her child with nourishment. That Jahi’s heart continued to beat under those circumstances redoubled Winkfield’s resolve to fight on her behalf.

Meanwhile, Dolan, Sealey and a group of activists that included the Terri Schiavo Life & Hope Network worked diligently to find another location where Jahi could receive medical care. Finally, on January 5, they removed her from CHO and placed her in an undisclosed facility that is continuing her care indefinitely. Yet even that triumph had a brutal twist: Consistent with the diagnosis of brain death (which had been accepted by the court), the hospital would only release Jahi to her mother through the coroner’s office. The price of continuing her care was Winkfield’s signature on a document acknowledging her daughter’s death.

The Jahi McMath case is only partly about the complicated medical distinctions between life and death. “I saw a lot of stereotyping about Black people in the public discussions about Jahi,” says Dorothy Roberts, J.D., bioethics expert at the University of Pennsylvania and author of Killing the Black Body. “There’s an idea that Black people make medical decisions based upon superstition and not scientific evidence. But really, Black people make rational decisions based on a real history of abuse and inhumane treatment.” Among respondents to a recent Pew Research Center poll on end-of-life decisions, a majority of African-Americans supported the idea that doctors should do everything possible to save a patient’s life, even in cases where improvement seemed unlikely. This response is not solely a product of religious faith; it’s also because physicians are less likely to aggressively treat Black patients compared with White patients. A 2008 study of the “equal access” Veterans Affairs health care system concluded, “Racial disparities appear most prevalent for…surgery and other invasive procedures, processes that are likely to be affected by the quantity and quality of patient-provider communication, shared decision making, and patient participation.” But this doesn’t change the truth about brain death. Marie Pasinski, M.D., a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital and instructor at Harvard Medical School, says, “If a patient has truly met all the criteria for brain death, there really isn’t a chance of recovery.”

Back in March, the Terri Schiavo Network honored Winkfield with its Life & Hope award, given to those who “fight to protect the dignity of a loved one against over-whelming odds.” Today, Winkfield spends her time at the private location where Jahi is receiving medical attention. Having read volumes of scientific literature on brain injury, she’s working to have Jahi’s death certificate revoked so that she can qualify for medical benefits. When relatives call, the facility’s staff places the phone against Jahi’s ear so that she’ll know her family is waiting for her, that she is loved, that she has not been forgotten. Winkfield massages her daughter’s limbs and polishes her nails. Marvin braids and rebraids Jahi’s hair. Together, they continue to sustain faith in Jahi’s tenacity. “I worried that she was the most timid of my children, but she’s the strongest,” Winkfield says.

Jahi McMath was born at 4:44 P.M. on October 24, 2000. She was two weeks overdue. Winkfield notices that time every afternoon and takes it as a reminder that her daughter operates on her own schedule. Jahi has spent seven months somewhere between the unknown and the unknowable. Winkfield has spent those same months willing her child along whatever path she travels now. “I know Jahi,” she says. “And I know my daughter would never want me to give up on her.”

This article was featured in the July 2014 issue of ESSENCE.