South African writer and poet Bongani Madondo writes his elegy to Muhammad Ali.

Just exactly what is God trying to tell us here? Surely God must know what heroes like Ali mean to us.

— Nathan McCall: Muhammad Ali: We cling to him (What’s Going On, Essays)

THE GREATEST was the fastest, prettiest, deepest, most vulnerable,most reliable in his convictions, never perfect, totally infallible, the embodiment of flawed beauty as a form of spiritual mirror reflection. In both his triumphant moments and at his lowest, at his conquering path and in his most challenged and tragic downward spiral, the man who suffused his second name with so much Black juice, spirituality and enraged, yet elegant power so that the entire universe got to know him as the single-named Ali, was a symbol of a rounded humanity mainly because that shit just doesn’t exist: Perfection? P-u-r-r-r-… Humanity? Who knows it?

Ali brought his beauty and brutality into it, his conviction and insecurity into it, his power and weakness into it, and in deed and silence, showed us we too can aspire for greatness and still settle for whatever God gave us in the moments all the number 1-spots have all been allocated. Because I refuse to speak of him in past tenses, this is what me and his spirit, wherever it is right now, possibly hanging out with Allah, the Almighty S/he, up in the heavens, or teasing up that Yoruba rascal-philosopher Fela Kuti, reasoning with Harriet Tubman, Nina Simone, Miriam Makeba, Minnie Riperton and Busi Mhlongo joyously questioning these Black Magic chanteuses about songs yet sung, or still standing on a queue in purgatory, shaking like a spring spring-leaf, about to answer for his sins, such as calling Joe Frazier “the ugliest m’fucker in the world’ or the painful silence on Malcolm’s excommunication from The Nation of Islam and his eventual assassination by a Black brotherhood in cahoots with the FBI…it don’t matter now, right now my earthily spirit stand, is queuing with him in purgatory, or in eternal release, if only symbolically, waiting for his card-number to be called. Ali is of us, for us, by us, eventually the embodiment of what Coltrane declared our Love Supreme: Our promise, ugliness, endurance, organic erudition and above all, irrepressible beauty. He is the air we breathe; the soul-channel through which we, if we dare so be as naked in spirit, could, and have channelled the most dispiriting of our challenges; challenges not quite peculiar to, though at the height of my Ali hero-fetishizing period (1976-1996), were undeniably experienced by my black, brown and Middle Eastern brethren and sistren, right across the globe.

Precious Moments Between Muhammad Ali and His Daughters

Ali is our teacher, brother; father and guiding light on how best and swiftly we should deal with those that seek to undermine our humanity. You listen to his oft’ deeply philosophical though wit-encoded exultations and appeal to the goodness in all of humanity, this ram-rod tall, straight-backed and elegant black leather jacketed brother wearing an Afro, and you know that although he seems to be the only one with balls of brass to stand up to massah, his poise and body language conveyed that: There are so many of us where I come from.

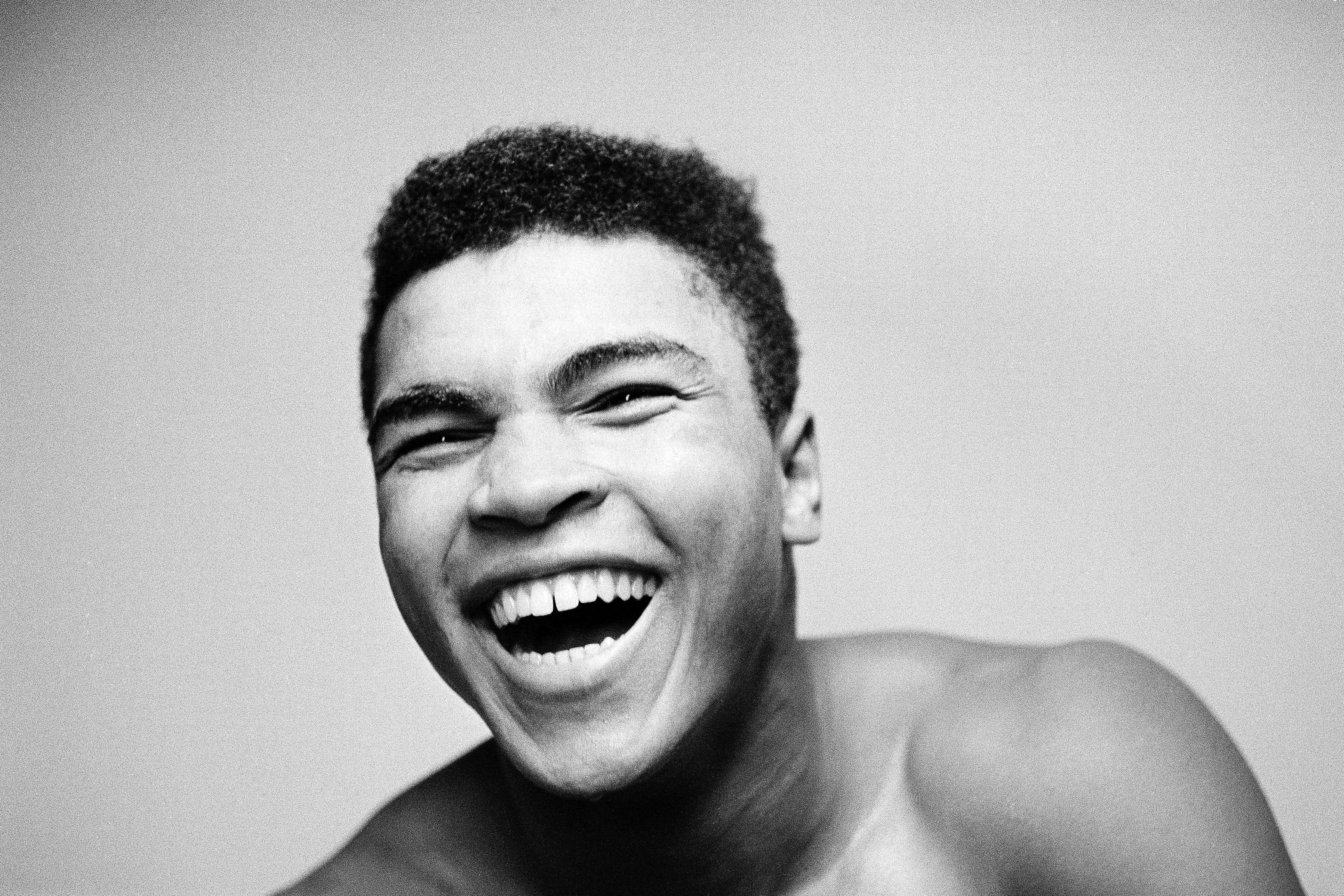

Scouring through millions of film, newspaper and magazine photo archives from Johannesburg to Kuala Lumpur, there alone in the dark dungeons of libraries and archives departments of major news media houses or small town village libraries, surrounded by dusty and yellowing, finger–staining old clips, and squat close to take in the emotion in the eyes of this most photographed of 20th century Black man, and what do you see? Let me tell you what I saw and still do every time I meditated over Ali’s image, especially those where he’s looking the camera in its inner eye: a disturbing, if only because it possessed rare and piercing calmness locked in the man’s eyes. A friend recently quoted Kafka on the imponderability of knowing another person at all and she concluded with this line: It is not because I am cold or callous that I am not making my home in and out of you…yet. And that’s the thing about Ali’s round, laughter-inducing eyes: You peered at them and felt like you could erect a home in this man’s soul. You look at him as a human being first and, inevitably a Black man, and you know too well that’s t’is way long overdue that you an African, Latino or child of the Maghreb, banish the idea that we who are darker than blue are inherently thieves, rapists, slaves, thugs, muggers, chattel labour, lazy and unintelligent. He’s our King Ali the 1st on the same canvas grand scale our beloved late Radiant Child Jean-Michel Basquiat equated him with that other flawed innovator, the Kansas Lightning as it were, aka Charlie Parker.

Muhammad Ali Was My First Black Superhero

MY BROTHER and friend Nathan McCall, a brother who writes with cleansing lucidity, once opened his essay on Muhammad Ali with this simple yet loaded observation: “Almost everybody has a Muhammad Ali story.” That’s like saying everybody has a Nelson Mandela story, right? In possibly the most beautiful narrative I’ve been transported through on Ali outside the sports and boxing literature, McCall asks rhetorically before answering it himself: Ali, Why do we cling to Him? We cling to because he reminds us—in this cold hearted, cynical age—that there’s still virtue in devoting our lives to causes larger than ourselves. We cling to him tightly and, for various reasons, needily. You might want to retrace your step and work your daring eyes and tongue backwards…like loving backwards as one brother once suggested, and drink-in that passage again.

McCall’s book came out almost 20 years ago to this day. In it, he also reminds us that Heroes are important. In their courage and selflessness, they give us ordinary folks higher standards to aspire to. “Heroes are valuable. Even the larger than life White ones manufactured in Hollywood and portrayed in history books.”

Yo, lemme tell you my non-existent story with Ali. Non-existent because I never got to meet him in flesh. And yet…well, I met the image and spirit of Ali twice. First I met Ali through the stories of beautiful men my mother enchanted me with growing up in the mid-1970s Apartheid era. The time was tense and tight as the innards of a golf-ball. Steve Biko had just been assassinated in cold-blood, for that’s what that murderous journey, stark naked in the back of a police van ferried thousands of kilometres to Pretoria was, but on the other hand mama’s favorite football team Kaiser Chiefs was whupping all opposition’s asses and winning everything on its path. Black was beautiful even if others were intimidated by our innate beauty. Through the transistor radio, mommy grooved to Kool & the Gang while I was, even that young, perving over Donna Summer and trying to make sense of her erotic piece “Love to Love You Baby.”

Momma said Ali would knock him out: referring to his upcoming fight with the front-gab toothed Leon Spinks. Leon, what kind of name is that for a Black man, anyhow, she frowned. Spinks knocked Ali out, which prompted momma to say, “It don’t matter.” No matter what, he will remain our Prince. He is our Ali. And she turned around, stepped into the bedroom and wept. I had no idea why a man momma never met would reduce my characteristically stealthy mama to tears. My curiosity was piqued. And then he died in my memory vault as the sequined and kohl-eye-lined 1980s and their mohawked hair-dos pouted into the scene and my acne played a revolution all its own on my face. Somehow though, The Greatest never really died. The obsession with him might have. Momentarily so.

Years later, I am an author and visual art fiend in Johannesburg. Somehow I had befriended the iconic photojournalist Alf Kumalo. “Bra Alf” became a legend before he later died (in 2012) and became, necessarily, by dint of death and body of his work…legendary. At his prime he was Ali’s friend, fan and visual biographer since he boarded a flight from Johannesburg to Berlin that May 1963 to watch Cassius Clay, then 18, fight. Their Black-Atlantic bromance and collaborations spanned decades and generations, criss-crossing the universe and surviving the Black Panthers, the juju sounds of Afrobeat and its dashikis, Black hippies bell-bottoms, the return of South African exile, the deferring of millions of poor South Africa’s dreams and the death of Joe Frazier. Alf snapped and chatted with Ali, slept at his house, attended mosques, events private and public, shot the man in his bedroom and everywhere else with relish.

Once “Bra Alf” felt, as it were, at home in your soul, he’d retell his “Ali and Me” anecdotes over and over, each a build-up and tangent to and from the last, all combining to create a stupendous You Don’t Say! eye-popping effect. “Let me tell you about the moment I was assigned to cover Rumble in the Jungle in Zaire, my boy,” he’d say. “The one where I was arrested six times in Zambia and Kenya, deported back to South Africa before I was allowed to fly five hours before the fight and arriving half and hour before the greatest fight took place. “Bra Alf “spoke in long sentences, punctuated by his cough-cough laughter. Every time I saw him, which was often the year he died, I’d besiege him to tell me that story and every time he would half tell another one, in Manila, or Chicago, or New York and then he would promise we meet for coffee so he could finally cough out his entire catalog of Ali tales.

One day we were supposed to meet at the Melrose Hotel in Johannesburg, and “Bra Alf” never turned up. I’d hear later in the week that he died that morning, October 21 2012. He was 82.

Ali died four years later. Although not quite their first names, both of them were called Ali at some timelines of their greatness in this sigh the beloved world, and if only as an endearment moniker. Neither of them is dead. After me yáll: Ali, Boomaye! Al-e-e-e-eh.

BONGANI MADONDO is a South African writer and amateur filmmaker who recently published Sigh, the Beloved Country, a collection of memoiristic essays on God, rock & roll, Black magic, race and music. You can find him on Twitter.