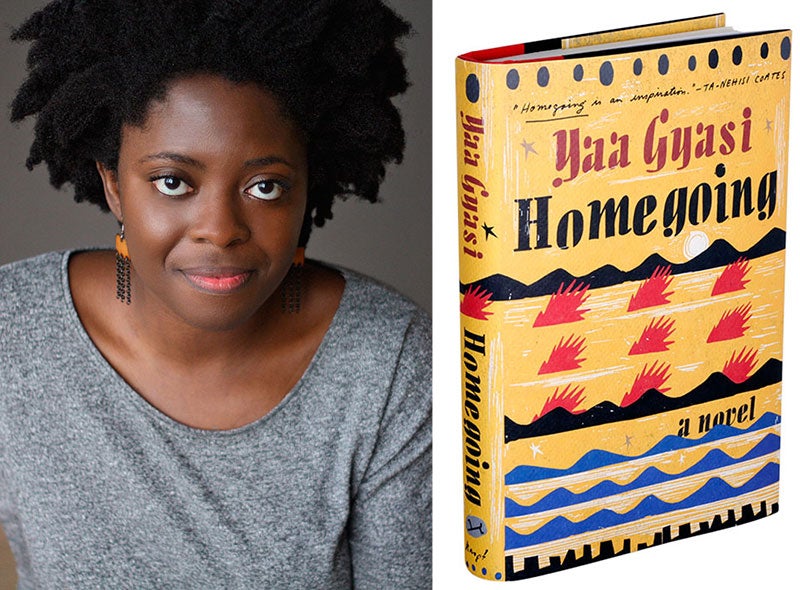

Remember the name Yaa Gyasi. At just 27 years old, the Ghanaian native has delivered Homegoing (Knopf, $26.95), her debut novel, and everyone from Ta-Nehisi Coates to the literati is raving about it. Here, the author gives us the details behind one of the “event” books of the year.

ESSENCE: Homegoing is historical and multigenerational, and it spans two continents. It is like those big Victorian novels or Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon (Vintage). Is that what you had in mind when you set out to write it?

YAA GYASI: I came up with the idea in 2009, when I had a research grant from Stanford University. I went to Ghana between my sophomore and junior year. A friend visited me and on a whim we went to the Cape Coast Castle. It opened up my imagination and became the genesis of this story. I wanted to focus on the first two characters, who are from the eighteenth century, and then on the last two, who are present-day. Three years later the structure started to materialize and I realized that what I really wanted was to look at a long stretch of time more closely. Those Victorian novels give you the idea that you can have something with as much depth and breadth as imaginable. Another book I read was One Hundred Years of Solitude (Harper Perennial) by Gabriel García Márquez. Reading his work made me feel that I had the permission to do something big and ambitious, and maybe a little messy.

ESSENCE: I can certainly see that with One Hundred Years of Solitude! Had you read Maryse Condé’s Segu (Penguin) at any point? When I read Homegoing, I thought that the only other novel that attempted to do this kind of thing is Condé’s Segu. Both feature contemporary characters trying to navigate an inherited history that they don’t always understand. Some have learned more about their lineage than others. Can you talk about the role history—its burden and gift—plays in your characters’ lives?

GYASI: In the African-American experience, I was struck by how fractured the families were because of slavery. It’s possible not to know who your great-grandparents or grandparents are. It struck me that you have this loss that goes on for generations. A character like H is cut off from his parents and his grandfather: That physical largeness, the brash power, the anger—all of it is his invisible inheritance. So that really interested me. Also I had questions about the differences between African immigrants and African-Americans. I grew up as an African immigrant in Alabama never knowing if I was Black enough or if I was Ghanaian enough.

ESSENCE: The novel offers two ways of understanding and narrating history: There is the academic and the creative/poetic. How do these approaches differ? What does the creative render that the academic does not?

GYASI: You can read an academic text and not really get it. There are a lot of great nonfiction works, like The Warmth of Other Suns, that show specific issues, that show us how they play out over time. But there’s something to be said for a creative work that allows you to feel it play out over a long period. Through the lies that fiction tells, we often reach the bigger truth.

WANT MORE FROM ESSENCE? Subscribe to our daily newsletter for the latest in hair, beauty, style and celebrity news.