There’s an inscription on the wall of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, whose doors will open to the public in less than a week. On the lowest level, in the exhibit focused on our nation’s dark history of slavery and segregation, a quote from the Crisis magazine asks, “Why must we remember?” A breath later, it answers itself. “If once the world forgets evil, evil is reborn.”

It’s no secret that the Black experience in the United States starts with the capture of our ancestors from their homelands and the centuries-long trade of people like commodities, followed by a lengthy period of institutionalized segregation and anti-Black policies. Freedom felt so far off for Black people that they couldn’t imagine a day when an African-American family would reside in the White House. But for decades, that story was left untold on the National Mall, where 18 Smithsonian museums tell the history of the American people’s spirit and their cultural fabric. It seemed as if, in a space that mattered, the nation wished to forget.

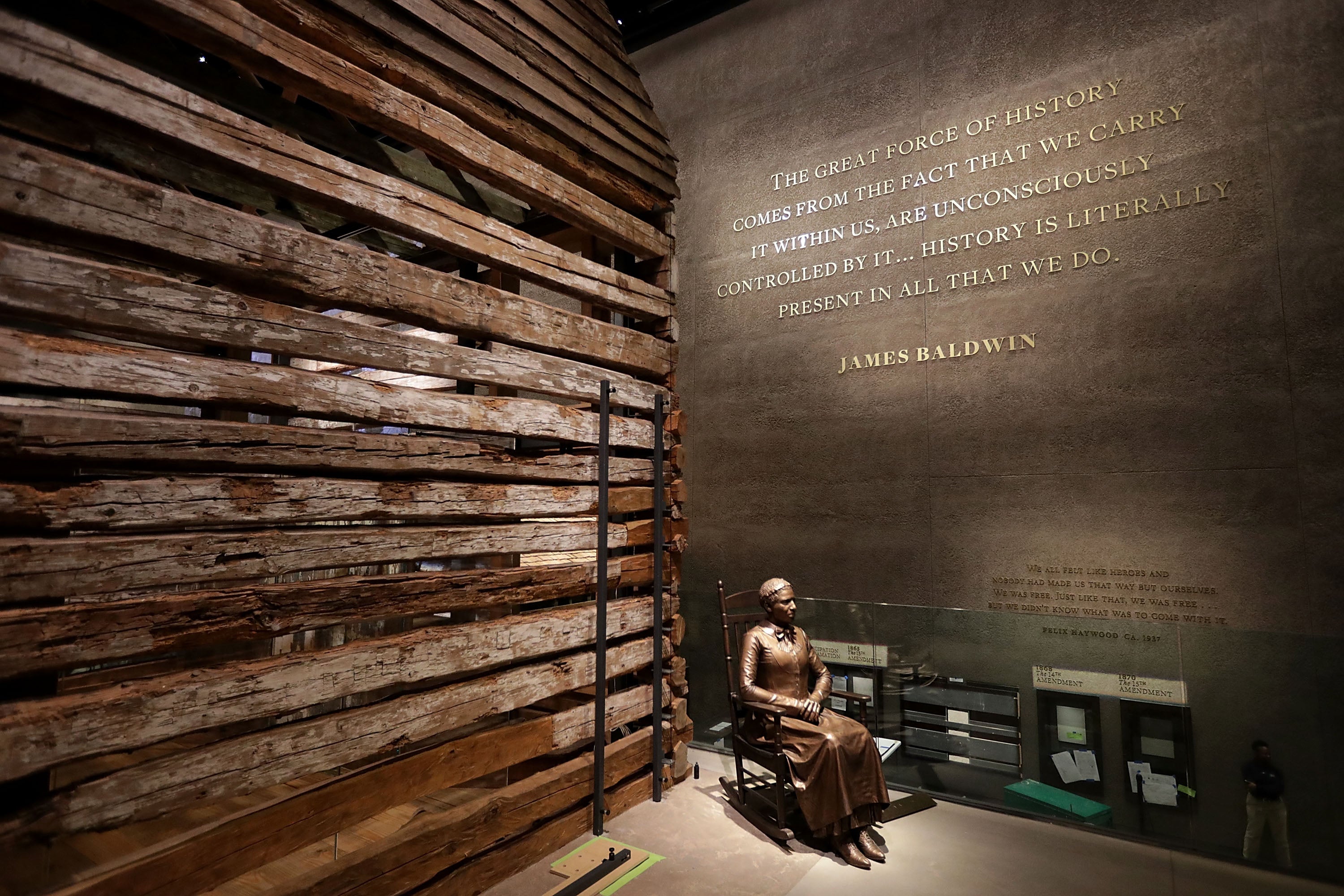

In a little over a week, that changes. On September 24th, the nineteenth Smithsonian Institution, the first to look solely at the experiences and cultural contributions of Blacks, will open to the public amid a ribbon cutting ceremony and celebration on the National Mall. The museum was designed with a vision of helping America remember the rich history of African-Americans, but also to tell the unvarnished truth, said its director Lonnie Bunch at a press conference on Wednesday. That’s why when visitors enter the ground floor of the museum, they’re greeted with the history of the African experience, the cultural and economic progress made on the continent prior to the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. From there, museumgoers will walk along a corridor where the brutality of the Middle Passage sets in.

“We felt it was crucial to craft a museum that would help America remember and confront, confront its tortured racial past,” said Bunch. “But we also thought while America should ponder the pain of slavery and segregation, it also had to find the joy, the hope, the resiliency, the spirituality that was endemic in this community.”

A couple of floors up, a reconstructed slave cabin, a segregated rail car, and a watchtower from the Angola prison in Louisiana, sits among a collection of Obama memorabilia—a dress worn by First Lady Michelle Obama and a bevy of magazine and newspaper covers that feature images of the first Black First Family. Just past that and through the halls, images of Black power and love are spread across a floor that encapsulates the beauty found within the Black American struggle—a beauty that was nurtured in community organizations and churches, among activists and actors, athletes and poets. On the floor dedicated to the ways Black Americans have historically made “a way out of no way,” the contributions of Mary McLeod Bethune, educator, political leader, and founder of the National Council of Negro Women, are highlighted.

The towering structure, built to resemble a crown, or corona, is a century in the making. What began as an idea for a memorial to Black members of the service in 1915 became a “tribute to the Negro’s contributions to the achievements of America,” a decade later when President Calvin Coolidge approved the idea. But time wore on and nothing came to fruition. Lawmakers, for their part, continued raising the idea but no plans took hold until 2003 when a bipartisan group of lawmakers, led by civil rights icon Rep. John Lewis, passed a law to establish what is now the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

WANT MORE FROM ESSENCE? Subscribe to our daily newsletter for the latest in hair, beauty, style and celebrity news.

A little over a decade, and hundreds of millions of fundraising dollars later, the building is set to open to the public just in time for the end of the second term of America’s first Black president. The Museum’s curators have amassed over 40,000 artifacts, many from everyday Americans, though only 3,700 are on display in the 12 inaugural exhibits. Among them are iconic pieces like Chuck Berry’s red Cadillac and a prayer shawl worn by Harriett Tubman, but there are also small things like a hot comb preserved by a family or a cast iron skillet passed down through another family for generations. The small pieces of history fit just as neatly into the larger narrative as the huge ones.

“America can be changed. It will be changed,” reads another inscription, this one on the third floor of the 400,000 square-foot building, bold white letters nearly popping off of the black wall. In the fraught political climate, where both presidential candidates have tossed out the word “bigot” and sworn white supremacists are seeking elected office, it’s easy to get caught up in the notion of a divided America. But history, a history that’s on display in the Smithsonian’s African American Museum, tells us that we’ve been here before.

And we’ve overcome.