Art is something that has always been a part of Arvie Smith’s life. Growing up in the deep South – Texas, to be exact – he was exposed to the arts through his grandparents, who were both educators. With supplies and books constantly at arms reach, it was only natural that Smith gravitated to it at some point. As he began to draw more, he fell in love with the creative process.

“I was really fascinated that I could make things look like real things,” Smith says. “So, that’s how I got started.” He would go on to sketch life observations, paintings from people such as Michelangelo, and more. But at the time, he didn’t feel that what he was doing was considered “art” – that was something designated for “white people,” he tells ESSENCE.

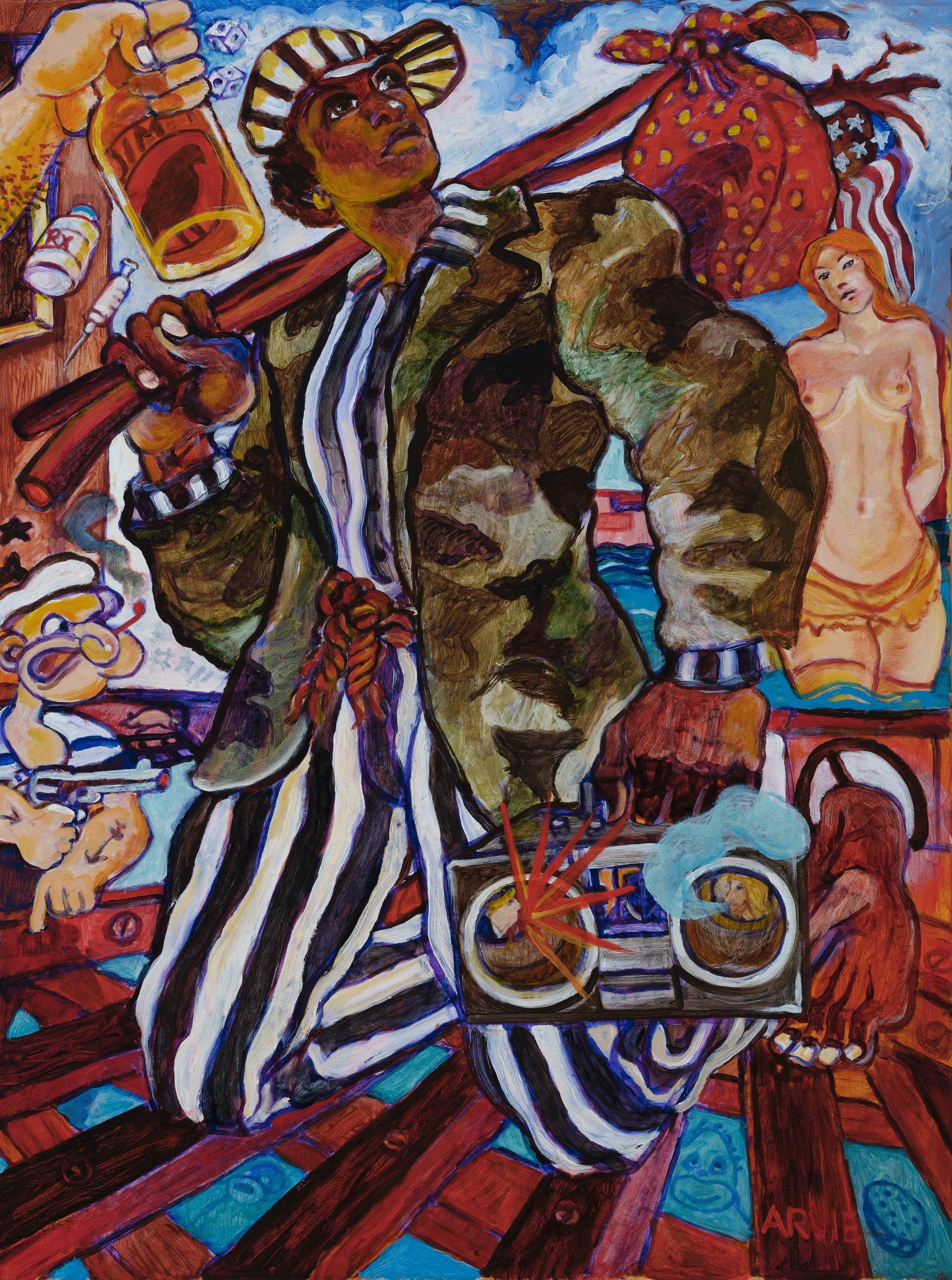

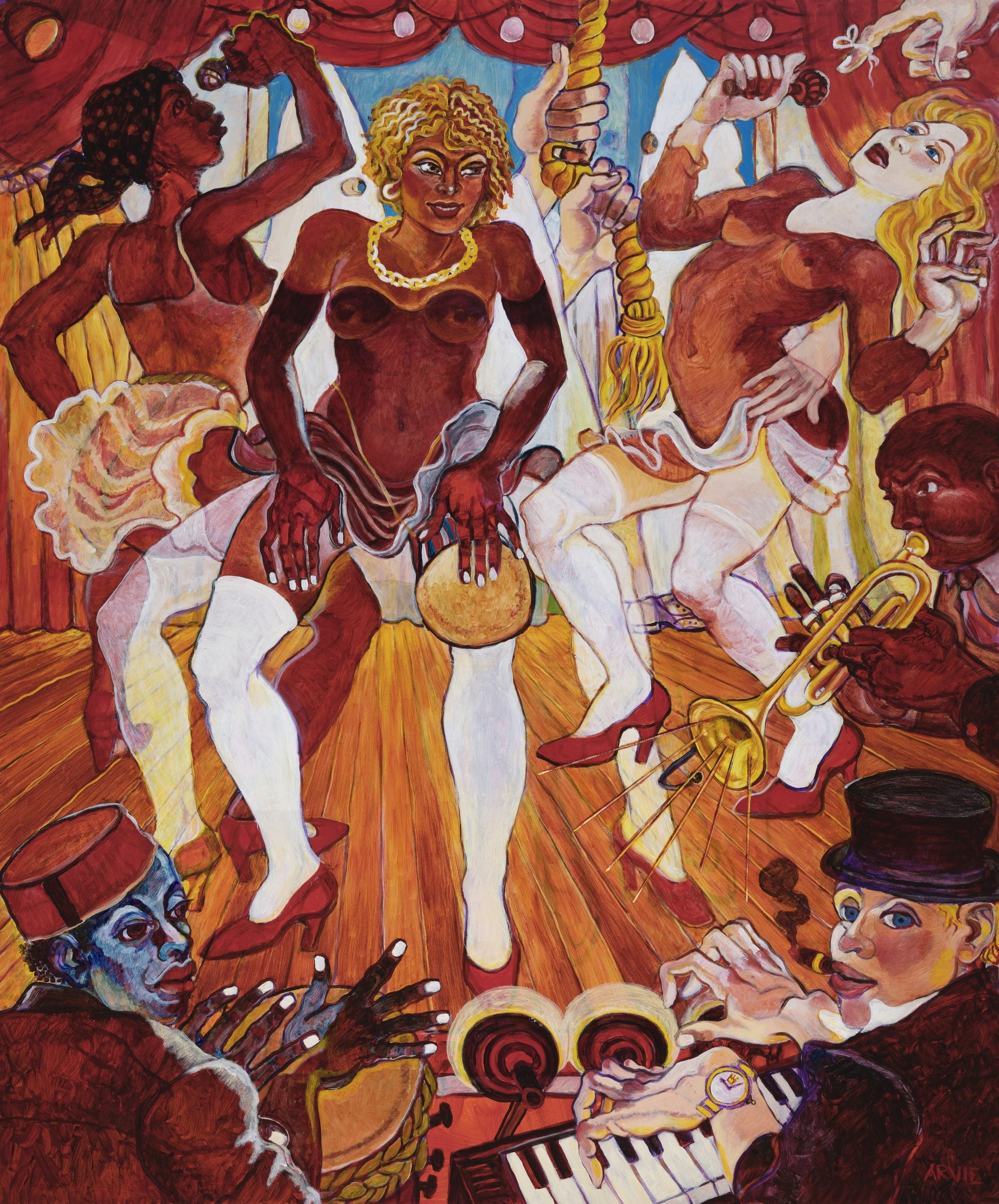

Ironically, themes such as race, and the social and human injustices in this country would come to define Smith’s work as a creator. Throughout his 40-year career, this award-winning artist has transformed the history of oppressed and stereotyped segments of the American experience into lyrical two-dimensional master works. His paintings use common psychological images to reveal deep sympathy for the dispossessed and marginalized members of society in an unrelenting search for beauty, meaning, and equality.

“We have to fight for recognition and we have to expose the discrimination in a way that people can hear it,” Smith says of his practice. “I can do that with my voice, and my voice is art.”

Smith’s voice can be heard at the Art Dealers Association of America’s Art Show in New York from November 1 – 5. Here, viewers will be able to see all new works from the Maryland Institute College of Art graduate. Presented by Monique Meloche, this will also be the first time his creations will be exhibited in New York City in over 30 years. At the seasoned age of 85, Smith’s ability to extract beauty from the painful situations serves as a testament to why he should be considered as one of the most important artists of his generation.

Do you remember how art came into your life?

Well, I grew up in the south, in Texas – Jasper, Texas, which is pretty much known for its racist views and discrimination. I grew up with my grandparents after my mother and father divorced. When I was about three years old, I moved to a place called Roganville, Texas, which is in Jasper County. I lived on a farm with my grandmother, grandfather, and my great-grandmother who was born a slave.

Myself, I’m just 73 years out of slavery when I was born. My parents, my grandparents, being educators, there was always art supplies around and books. I went to this one room class school for all the black kids that my grandfather started and my grandmother taught there. There were always art supplies around. I did a copper tooling of my horse and I gave it to my great-grandmother and she made a great big fuss over this.

I said, “This is kind of nice”, because I had a little brother and he’s getting all the goodies, but I could draw, and so could he, but he gave it up. But I went on and I was really fascinated that I could make things look like real things. And so, that’s how I got started. My grandfather gave me a book on Michelangelo. I copied pretty much everything in that book. I went on from there. In grade school, I think it was junior high, I had a teacher, Ms. Britter, and she said, “Hey, you’re pretty good. Why don’t you paint the people outside the window?” I said, “I’m painting chairs, I’m painting white people.” At the time, I didn’t think about painting being art. That wasn’t art. What white people did, that was art.

So when do you think your perspective changed when it came to art? And what motivates you to continue your practice today?

Well, I felt that the stuff I was doing were just cartoons and irrelevant, but what kept me going is the encouragement from my family. My mother, while I was a juvenile delinquent like all the other kids in LA when we moved to LA; my mother took me to museums and I got a taste of art. “This is something that, somehow, I feel connected to,” I said to myself. I think a lot of that had to do with my great-grandmother and my grandmother making their quilts. So, in the country, I’d watch them sitting around this circle making these crazy quilts. My instructors later on asked me, “Where do you get that color palette?” I didn’t know. And then, I thought about it a while, and it’s the crazy quilts. We took every scrap of things that we had and made a quilt with it. I have the quilt today. My grandfather always wore a suit to work because he taught at the college and he taught at the school.

He always wore these suits and a little vest. I have the quilt that they made from his suits. That’s about all I have left from him, but he was great. He was a real inspiration. He was working on his PhD when we were little kids, and I thought that was amazing.

I finally got an honorary PhD later on in life, which is a little different, but it was cool. The thing that keeps me going is what I experienced in the south, like stories of my uncle getting killed down in Sawmill. We were the only blacks that lived on this side of the tracks because of land that my grandfather acquired. It was pretty rough because people would destroy our crops and stuff like that, but that perseverance and determination and hard work is something that I got from my grandparents because that’s what it took to survive. If you run out of food, you go kill something – that was the reality of it. We grew everything for the most part, and we stayed pretty much on the farm. My playground, my brother, sister, our playground was the burnout house plantation of my great, great uncle.

One day, my great, great uncle’s house was burned down by the clan, and he had to catch a train to LA to get out of there. But it was that kind of life and death thing that informs you that there’s something sinister out there and people might ride up in white sheets and do you harm. As a child, you understand that. You get it. You’ve never seen it, but you know it happens. That’s the mentality that you grew up with, that something’s not right here. This is not justice. I’ve dealt with that for the rest of my life, bringing that to the forefront that we have to fight for recognition and we have to expose the discrimination in a way that people can hear it. I can do that with my voice, and my voice is art.

Growing up in Texas and Los Angeles, did you see or feel any similarities in the black experience?

No, man, it was a whole different ball game. It was very strange. Actually, in the south, I’d never seen a fight. We didn’t fight each other. But when I moved to LA, that was the name of the game. Somebody, especially a kid from the country, you have to prove yourself that you’re the strong country kid so people didn’t push you away from the table too often, but it was a real culture shock for me.

People were calling their parents by their first name, smoking cigarettes, drinking wine, all that stuff, I’ve never even seen. In fact, in the country with my grandparents, these were called Honky-tonk people. Actually, I’ve done a couple of paintings on that. But yeah, it was a real culture shock.

I was looking at some of the work that you’re presenting at the art fair, and the one that stood out to me the most was The Three Graces. The main thing I got from it was perception, how we perceive ourselves, how other people perceive us. Why do you think it’s important for you to break these negative stereotypes about black people through your art?

Because it’s my voice. Nobody can stop me from saying what I want to say. Now, in teaching for over 20 years, that wasn’t exactly the case. You’re under the purview of the school, of the institution, and you have to go along with that and you don’t exactly raise your voice. Higher education is not an equal opportunity situation for black people. You’re always fighting just to keep your head above water. Even though what you’re doing in the classroom is way above, in my own opinion, way above what some of the other guys are doing, but you didn’t necessarily get that kind of recognition.

Earlier, you spoke about the educators in your family. Did their influence inspire you to become an educator as well?

I didn’t know what I wanted, like most kids. Every now and then, a fair would come to Jasper. And so, I went to a fair and there was this fortune-teller. I said, “Grandpa, I want to go talk to the fortune-teller.” The fortune-teller told me, “What do you want to be?” I thought about it, hell, I didn’t know what I wanted to be. I said, “I want to be a doctor.” She said, “You can be anything you want to be”, and I believed that, but my direction went toward art, not toward medicine. I thought it was pretty ironic when I got this honorary PhD that the fortune-teller was right. I went toward art because that’s what I loved. It was my strong suit. I also loved music. Everybody, there was always music around. They bought my sister a piano, and I tried to play some instruments. I kind of play the flute now, but art was my voice and something that I did that I thought I did well.

Most of your work looks at the black experience with a humorous tone – why do you think it’s important to do that? Do you think it makes it more digestible to the viewer?

So people will listen. I would like for people to listen. Sometimes, I’m just having fun. I see some people struggling to get a leg up and it seems to me that they think because they have this institutionalized white supremacy, they really believe it, and I don’t. It’s always that struggle. But most of the time, almost all the time, I’m outnumbered. That’s why I do it. I want to tell my truth, but my truth is not awful. My truth is, you all have to look at something else. This isn’t working for me and it’s not working for my people. We’re Africans. We’re people of African descent. I spent a lot of time in Africa, and we are beautiful, beautiful people. I knew that just from my grandparents. The story is that my grandfather’s dad was Ethiopian and came from Ethiopia, and my grandfather identifies as Ethiopian and he always talked to me about Timbuktu.

I thought this was just some made up thing. I’ve been to Timbuktu. I brought stuff back from Timbuktu. And so, it’s full circle.