Since last year, Julie Mehretu has split her time between New York City and upstate New York, in the Catskills.

“It’s really beautiful, pristine, incredible land, right by a river,” she says, her voice clear and soothing. “And it’s beautiful mountains and vistas and wonderful hiking.” The surrounding landscape is the embodiment of what one imagines as the perfect canvas for an artist—except free of the posturing that sometimes accompanies modulations of those who create for a living.

Usually based in Harlem, when in the Catskills, Mehretu uses a studio space that doubles as an artist residence. There, she has found herself focused in a new way, able to “capture stillness” despite the havoc of living through the past year—the pandemic and the politics. “As an artist, it’s really been a fertile time that way,” she says.

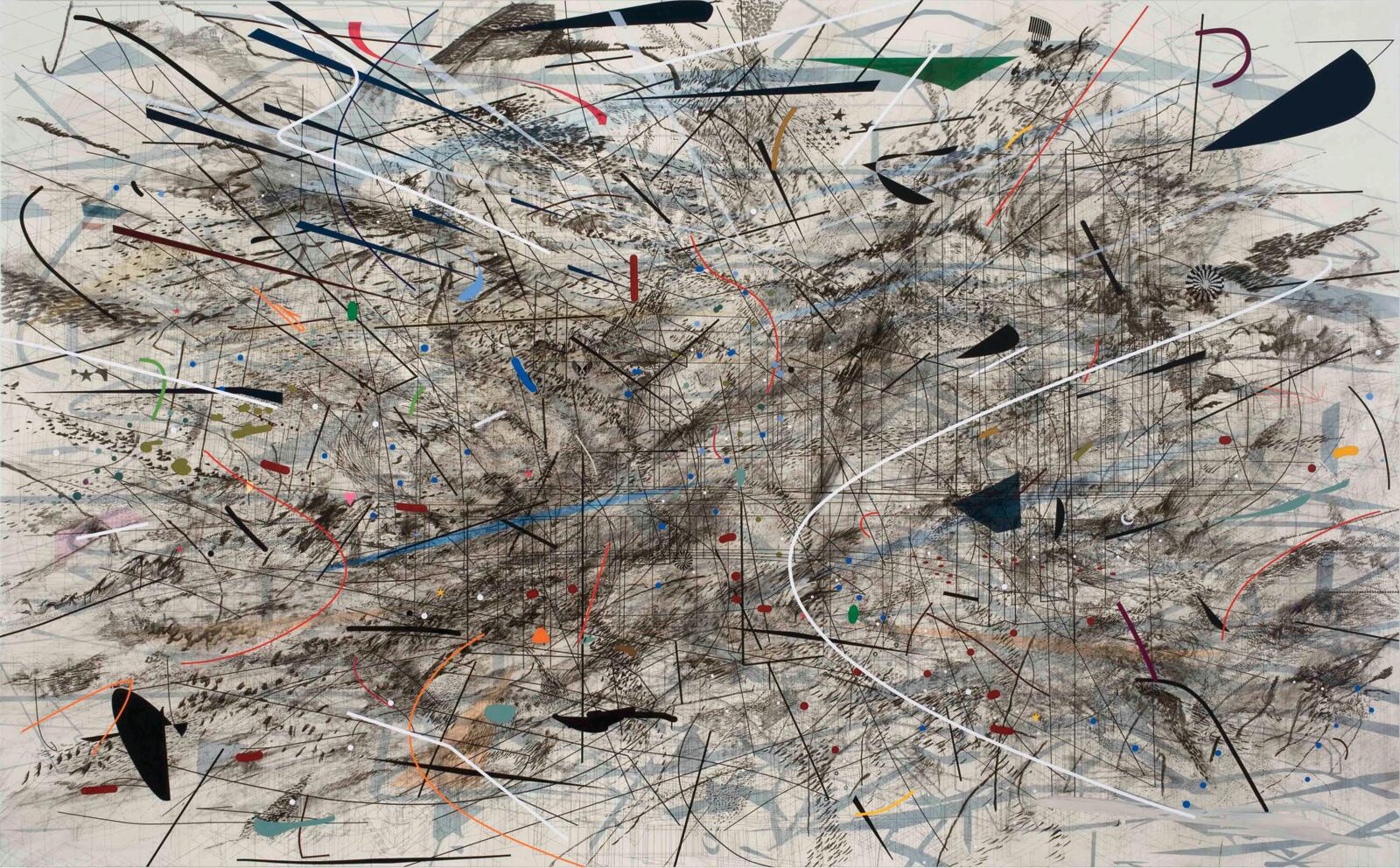

An Ethiopian-American contemporary visual artist who made Time magazine’s “100 Most Influential People” list for 2020, Mehretu will have a comprehensive survey of her work displayed at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, beginning March 25. More than 70 paintings, prints and drawings, spanning 25 years of her career (from 1996 to the present) will be included. The work bears witness to a plethora of approaches and techniques, from cartography to Chinese calligraphy—plus architectural drawings, graffiti and much more. The outcome of this versatility of inspiration has for decades formed nuanced, multilayered abstracted images, allegorizing commentary on various socio-political realities and capabilities of urban life in different spaces.

It’s altogether powerful, impressive and befitting of Mehretu’s contributions. It’s also rare. Celebration in the art world arrives notoriously late, sometimes posthumously. For those who exist at the margins, this is particularly true. Mehretu, cognizant of the larger meaning of this exhibit for a mid-career artist, is especially aware of its implications for a Black artist and a woman.

“To have that kind of recognition and that kind of support and that type of audience that comes from it, from being in an institution like the Whitney, what that offers other younger artists and the community is really important,” she says over the phone, her words chosen like an intentional melody of idioms written for song. “And so, in that sense, I feel like it’s profound. I feel very honored by that, and indebted to all the artists before me.”

Those proverbial debts are paid to painters like Sam Gilliam and Howardena Pindell, both of whom also use mixed media. Mehretu’s influences also include Guyanese-British abstract expressionist Frank Bowling and the late, great painter and sculptor Jack Whitten, who received the National Medal of Arts in 2015. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art’s showcase of his work came three years later, in 2018— seven months after his death. Thankfully, Mehretu is getting her flowers now. Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 1970, Mehretu left for Michigan with her mother when she was 6 years old. Her father would join them shortly after. She vividly recalls her early days in the Ethiopian capital, the painful adjustment to life in a new country and the loss of innocence that accompanied it.

“Not having that extended family and not having that kind of deep bonding, of seeing who you are reflected in that larger society as a whole, was really kind of a change,” she says. With a subtle shift of having yielded to something larger than herself detectable in her voice, she adds, “I feel like then you become a different kind of kid after that.”

Mehretu would go on to attain a B.A. in art from Kalamazoo College; she also studied abroad at the prestigious Université Cheikh Anta Diop in Dakar, Senegal. She earned her M.F.A. from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1997; and soon after, moved to New York City, where she began to cement herself as one of the nation’s most invigorating artists, obtaining the MacArthur Fellowship “genius” grant in 2005.

Mehretu’s work would take her all over the country and the world—Berlin, Cairo, Lagos and more—and she reflected the chaos and prospects of big cities in her abstractions. These early works contain idiosyncratic notations and marks that she refers to as “agents,” using circles, dots and even life forms like insects to portray the mass migrations at the center of urban life. They were also inspired by her childhood: She describes her parents as “Africanists” and, notably, her father worked as an economic geographer focused on African development. He directly informs her use of aerial maps of African urban centers in major early paintings, in which she layers precolonial structures and postcolonial “squares of independence,” as she calls them, atop each other.

Coming of age surrounded by an African community in Michigan, she observed how the liberation aspirations of postcolonial Africa became stifled by corrupt governments. “That has been really formative for one of my big questions in the work,” she says, “which is the possibility and Utopian hope that get co-opted, and the liminal space of that hope.” She quickly corrects herself: “Hope is the wrong word; but it’s that space of possibility.”

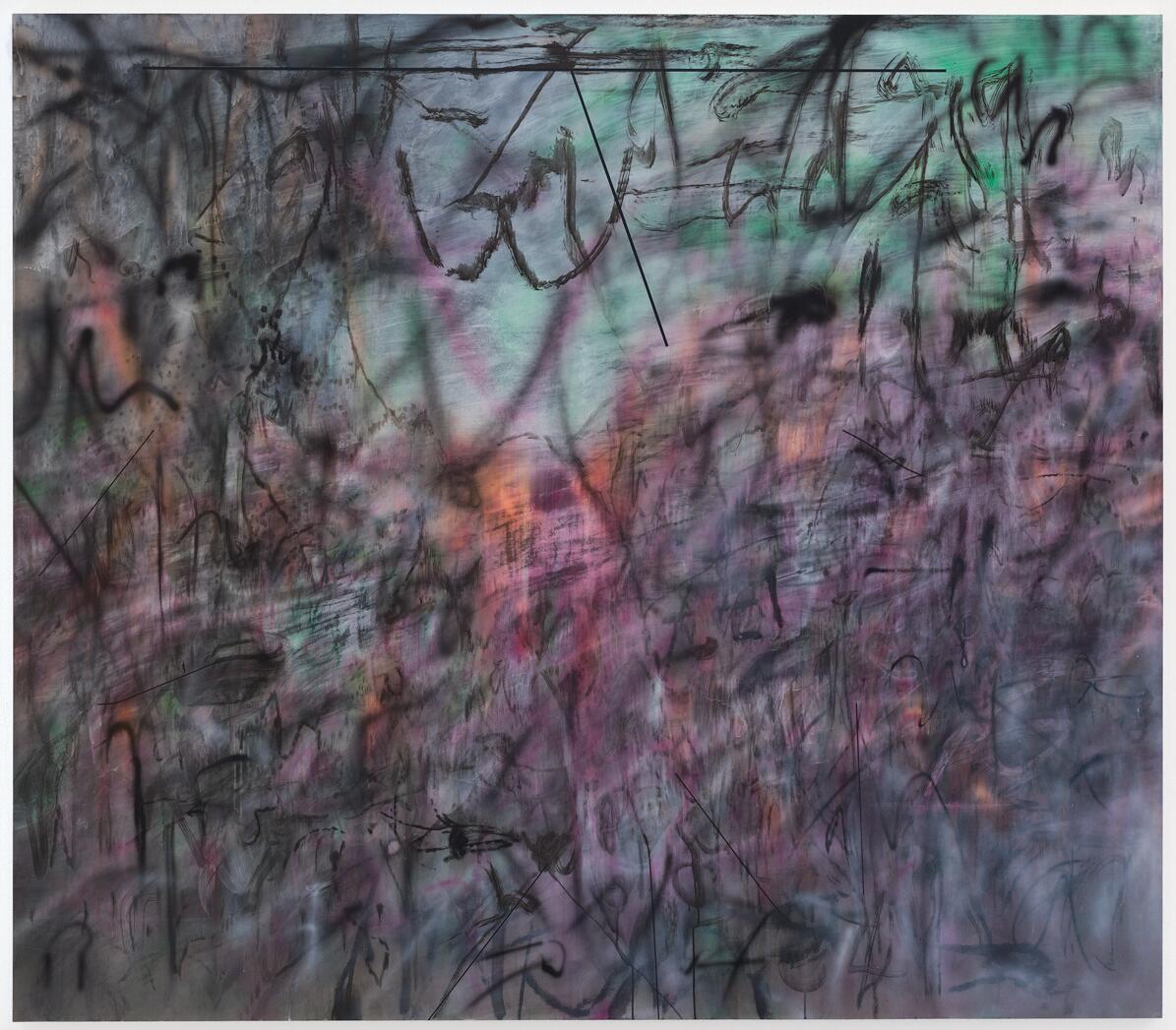

After 2010, moved by the Arab Spring, she continued through a “Grey Space” period—not so much retreating from the use of color as having been propelled into occupying grey in her paintings. “The gesture really started to try and invent itself and find a different place of freedom and liberation,” she says, adding that that movement, too, would be co-opted. Stemming from the climate crisis, riots in London and Paris, and the beginning of the Black Lives Matter movement, Mehretu’s work shifted again. Her recognizable “notational mark-making” was so intense, it became contorted smudges and blurs. Sometimes she used photographs as a base—at first only black and white, then returning to color.

The consciousness of harm on Black bodies has always been present in her work because they are part of an American consciousness she adopted. Still, the transnational dangers Black bodies face—occurring simultaneously with the far-right resurgence—was the backdrop from which more blurs emerged in her artistry, extrapolated from a centuries-long nightmare. “When Trump was elected in this country, it brought up a deep, haunting and kind of horrific past that has never been negotiated,” she says.

But for Mehretu, whose art is ultimately in conversation with vulnerable people confronting power around the globe, the conclusion of struggle is not the point: It’s possibility. And what is possible is the question she seems to be asking over and over again in her art.

Though she is unsure how her work will evolve during the trauma of this pandemic, the motif is as clear as ever: invention as dissent and dissent as invention, from one space to the next. As she puts it, “Even within culture, there’s this need for disobedience, and invention for liberation.”