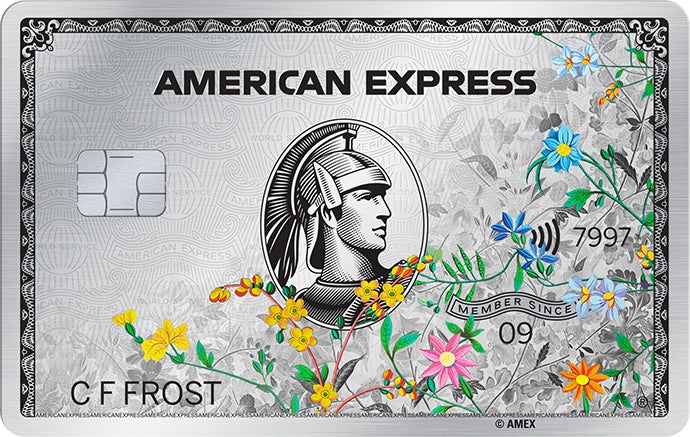

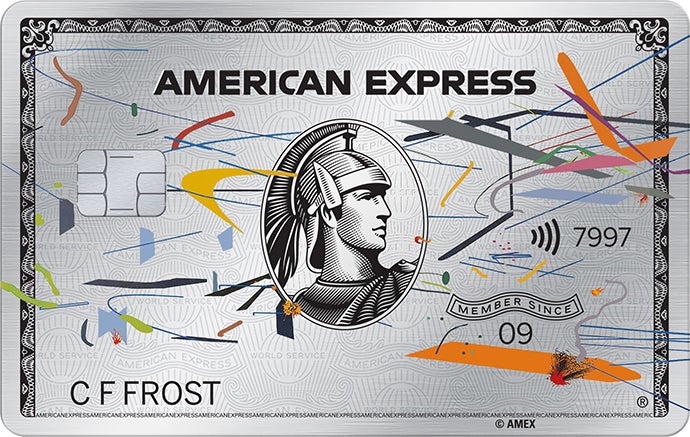

During Art Basel in Miami, American Express announced that it had tapped word-renowned artists Julie Mehretu and Kehinde Wiley to reimagine its Platinum card for the new year. Available to existing members beginning January 20, 222, the cards incorporate each creator’s signature aesthetic — Mehretu’s being modern abstract art and Wiley’s naturalistic portraits.

The partnership is an extension of the work each has already begun with the brand, with AMEX announcing the creation of a $1 million fund in sponsorship to The Studio Museum in Harlem during a talk with Mehretu and Kehinde there late last month. The money will be used to “support its work as the nexus for artists of African descent, locally, nationally, and internationally.”

We got a chance to speak with Wiley and Mehretu about the significance of Art Basel for creators of color, the impact of their partnership with AMEX, and how the everyday admirer can show up for Black artists.

You’re working with AMEX in a number of ways this year, what can you tell us about your partnership?

KEHINDE WILEY: Amex has been an amazing partner in terms of understanding what I want to do with this artist residency program –where my DNA comes from in terms of the Studio Museum of Harlem, and the way that they really sort of gave me my first shot out of the canon.

And when the conversation started, it was really more about how my aesthetic can be reimagined in a way that works on a card and how it feels like a natural confluence. I think if you look at my paintings, you can tell that there’s something going on with regards to class and status and replacing figures from a museum space with young folks who happen to look like me and really playing with that question of ambition and desire to be sort of in that kind of elevated space, right? So all of these conversations really made sense for me. It really felt authentic and not something that was much of a stretch for me.

And then just the fact that they would have this kind of engagement with the Studio Museum in Harlem, the idea that they could help fortify institutions like that which really, for me are kind of a no-brainer. Every time I talk about my rise as an artist, I always talk about Christine Kim. I always talk about Thelma Golden, I always talk about the three artists in residence who were there at the same time. You know what I mean? Just that sense of your own tribe, your own group.

JULIE MEHRETU: I was super honored that they asked me and the collaboration has really been around this kind of imagining, using part of my earlier painting and creating a design for the card that can be used as an art. And the support really came about through the offer of wanting to do this project together and work creatively together, but also an immense amount of support for Denniston Hill, this non-profit that I started with two collaborators and a group of collaborators and other artists.

It was started to kind of try to think, have artists, bi-POC queer artists come together to reimagine and build a place of artist residency and many other types of programs to think through what are important issues of our need in a safe place that is nurturing and nurturing each other, in an atmosphere of care, an atmosphere of immense possibility, radical imaginative thought. And we really see artists as these artists of all medium, as these agents of possible transformation and necessary agents of transformative art. And so this is a space that works as a think tank, a laboratory, a farm of an agricultural project and artist studios, performance space, film studio, recording studio… It’s really special.

How important is Art Basel to Black artists?

JM: It depends. Some artists enjoy them quite a bit. I mean, for me, I just always get this feeling of there’s a lot of events, interesting work happen along the periphery of the fair itself.

I think the actual fair itself, it’s really a market; it’s a marketplace. And that can feel very demoralizing because a lot of time and energy and work goes into the creation of these really important, or dear pieces to artists. And they can feel diminished in the context of the large expo warfare type of thing.

I think you can imagine the same in music. Can you imagine like an enormous music fair and all these musicians are like, “Who’s getting the most attention? Who’s going on?” It’s demoralizing to a certain degree. So, I’m not saying they shouldn’t exist but they’re just not this place for me to go hang out.

KW: Basel is at the heart of the global art market in terms of people collecting, looking. If you’re interested in contemporary art, it’s one of the few places where you can see so many different types of work presented almost as though it were a ready made museum. That provides an opportunity, but there’s some problems with that too, right? For a lot of artists, they’re kind of pressured into making a lot of work.

I always tell a lot of young artists to find the fortitude to resist the market pressures because this is the new dynamic which took over brick and mortar. It took over traditional art galleries. So most collectors now they go to places like Basel, they go to Basel, Switzerland, they go to Hong Kong. And these are all before COVID. This was an amazing way to see all this great art.

And also they get to have an art education as well, right? To become relatively quickly familiarized with who the artists are, not only in America, but all over the world. And that’s something that I’m becoming a lot more familiar with because now I’m running my own artists in residence program.

When it comes to sentiments like “Support Black Art,” what does that look like to you? How do you want to see the every day person Black artists?

JM: I think there’s a lot to think about when we think about art. First, there’s an immense amount of growth in arts education and certain communities are super privileged. I grew up in the Midwest where we didn’t have any contemporary galleries. And if you don’t have contemporary art, you don’t know the contemporary artists who exist and are making contemporary art, unless you have parents that are really tapped into something else. And I think that also comes from a very special and specific socioeconomic societal position. So I think one of the important things is to really realize the radical potential and importance of visual arts and that it’s not something that just lives in these kind of very pristine closed walls of a historic museum, but this work is part of a culture of change, a culture of transformation, a culture of radical thought. And that everyone has a place in there. Everyone has a place in the museum. Museums should be, as far as I’m concerned, free and open to the public, as much as possible. We should really encourage to build who comes, who experiences it and who’s inspired by it so that we can have more and more interesting work being made.

KW: I think that there’s different levels to the game, right? You can find artists who are just getting their start and their prices are approachable and you can find them now online. And there’s so many young artists now who are trying their best to get noticed and to be seen. And what they need is a sound collector base. And I think it’s exciting.

It’s an exciting time for African Americans to start creating communities of concern that support artists like us who happen to look like them. And it’s a unique time because prior to now this was sort of an impossibility. It’s also something that’s starting to become a lot more sexy in the culture. You’ve got Swizz and Alicia, you’ve got Jay and B, I mean, come on. Everybody now is checking for it in a way that makes it seem aspirational for that next generation of doctors and lawyers and thinkers coming up asking how do they want to spend their disposable income? And it’s a lot better than things that depreciate. So I think it’s a much more economically responsible option in terms of how to invest and also how to support your community at the same time.