For Penda Diakité, art has been a pivotal part of her life for as long as she can remember. As the child of two artists – her father a ceramicist and mother a sculptor – this Malian-American is fully aware of her heritage, as well as the true meaning behind the art she creates.

Growing up in both Portland, Oregon, and Mali, during her formative years, Diakité feels that there sometimes can be a sense of “not belonging” to a certain community at times. This life situation has given her a strong sense of empathy for the people around her, along with having compassion for the struggle that Black women face not only today, but throughout history. It was these factors that partly inspired Penda’s current exhibition at UTA Artist Space in Beverly Hills, the aptly titled Mansa Musso.

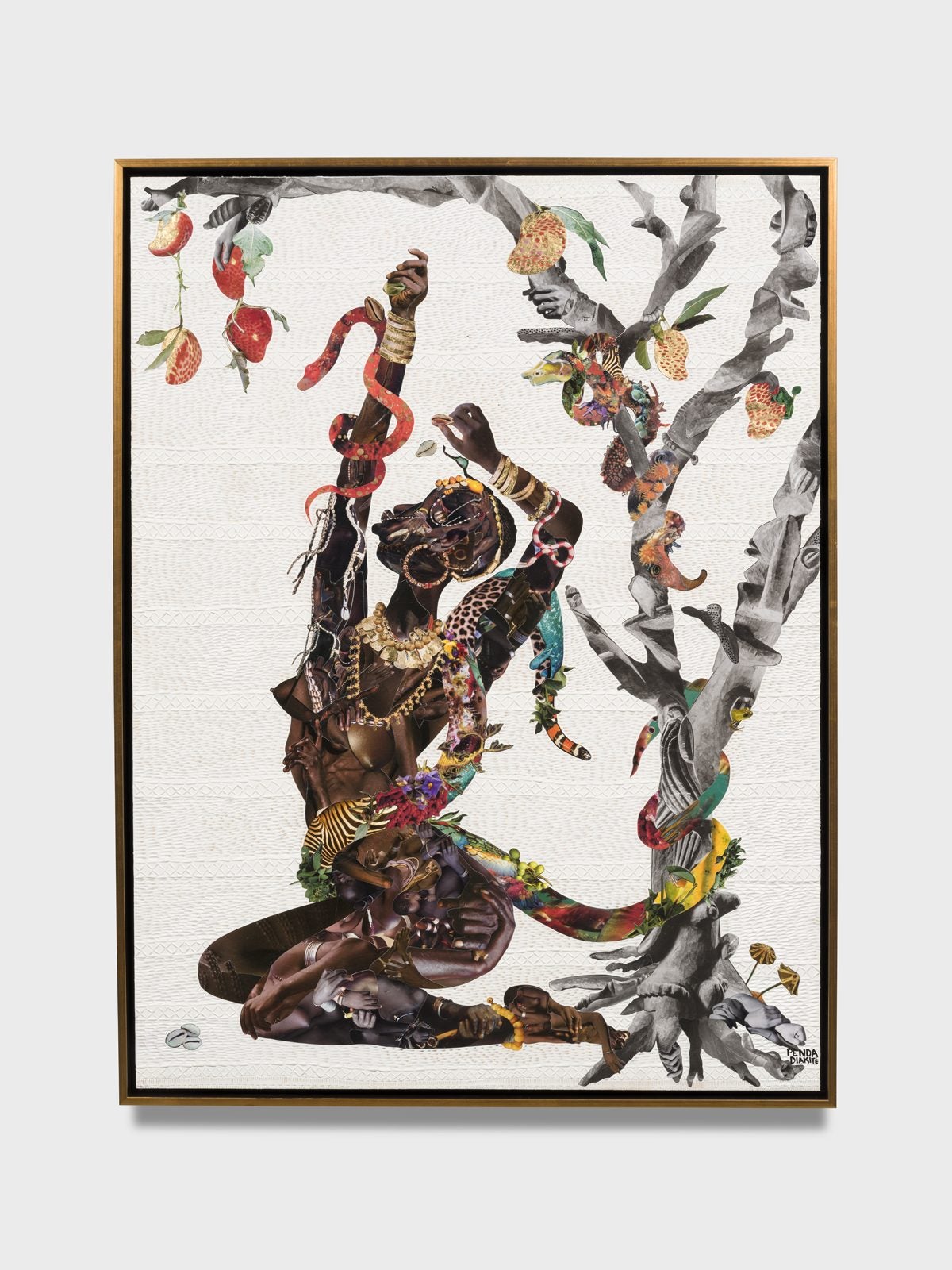

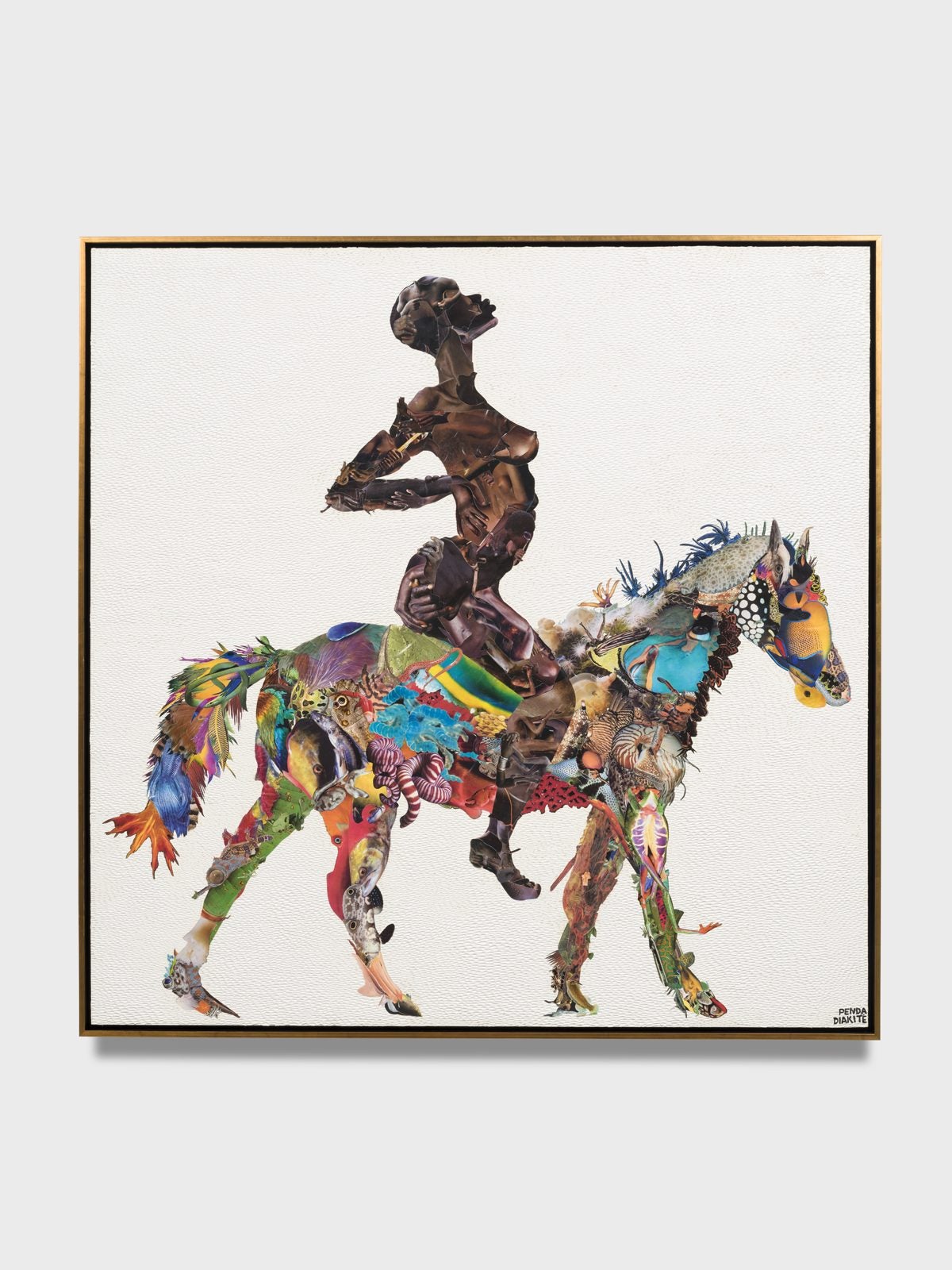

The powerful name of Diakité’s collection of work has the translation of ‘she is king,’ which is appropriate because the exhibition itself is a celebration of the women who played pivotal roles in the creation of the Mali Empire, without whose contributions there would be no West Africa as it is known today. The California Institute of the Arts graduate spoke to ESSENCE about Mansa Musso, the stories she wants to tell, and the revolving perception of Black women globally.

“It’s been a longstanding history,” Penda says. “It’s interesting because Mali, in a way, the essence of the culture, I would say is very, I guess, feminist in a way. There’s a lot of power in women in the culture. So a very, very easy example is in Bambara, which is one of the dialects that we speak, a dialect of Mandinka. So in Bambara, when you say thank you, we say “I ni cé,” and the men say “n ba,” which means I owe it to my mother.”

“So it’s very ingrained in the culture and the language,” she adds. “But then somewhere down the line, it’s just been historically that a lot of the women’s stories have been overshadowed, and it doesn’t mean that there was less of a story or less significance or power behind it. They just seem to have not been relayed at the same rate that the men’s stories were – but we’re changing that.”

Although this exhibition technically took about two years to complete, for the artist, it has been a lifelong journey. Drawing from conversations she’s had with griots and storytellers in Mali, Diakité created a body of work depicting life-size portraits of influential women in West African history. “These are really, really important stories that need to be out there more,” she says of narratives that these canvases are meant to convey to the viewer. As she compiled more information from the elders in her native country, Diakité began to question why these monumental women weren’t receiving the proper respect from an archival standpoint.

“I realized that a lot of the women in these stories were almost overshadowed by the king stories,” she says with a piercing gaze. “So, I kind of took those stories and delved deeper into the women’s histories behind that. And that was, over the past few years, when I really started delving into the women’s stories and realizing just how much power and cultural wealth there was in their stories.”

A large part of why Diakité is creating these paintings is to promote the chronology of the Black experience, especially the ones that aren’t being taught. Many people in Mali and the United States, don’t have access to this type of information. “So what I’m doing is I am creating this art to put these stories out there and to have these stories be out there for the public, and to be told, and to learn about our history,” she says.

Stories such such as that of Sogolon, whose son Sundiata Keita brought unity and prosperity to Mali, and Kankou, Mansa Musso’s mother, who was the backbone of the wealth and knowledge attributed to her child are all powerful tales that should resonate with people of color and beyond. Penda, however, hopes that her groundbreaking exhibition will serve as inspiration for Black women everywhere. “I want them to be able to learn a little bit more about themselves and their history and feel empowered and to see really where they came from,” the 31-year-old artist states. “Where there are women like them that have done incredible, incredible things and we’re here really because of them.”

In addition to giving a sense of self-awareness, confidence, and pride to the people who look like her, Mansa Musso is also an effort to shift the degrading narratives that Black people have endured for centuries.

“I feel like there needs to be more positive stories of our history put out there,” she says. “And it affects people’s perceptions of black culture, and unfortunately black people, when the histories and the stories are perpetuating negative stereotypes. So, through this, I’m trying to perpetuate those positive stereotypes, positive stories, and these positive narratives behind blackness.”