An old, common misconception of witches is that they’re all white. Another is that they’re associated with the devil. African and Black American culture has long included non-traditional spirituality that’s been misunderstood by white communities, as well as our own.

“The devil’s a Christian thing. You guys [Christians] came up with that. That doesn’t actually play into witchcraft as I know it,” says Mya Spalter, a Black witch and the author of Enchantments: A Modern Witches Guide to Self-Possession, to ESSENCE. “It’s just a totally different thing.” Practicing witchcraft is often portrayed as the opposite of Christianity, which is just untrue, she also notes.

While her book received generally positive reviews, Spalter says how her book will truly impact the conversation about Black witches is still up for debate. She does believe there’s been an explosion of young adult books featuring diverse stories in the years since her book was published.

“I find it incredibly exciting that ‘queer brown witch’ books are a whole section at my local bookstore. I like being a part of that cultural shift,” Spalter says.

The shift of Black witches and witches of color being respected and included in history is overdue.

Read ESSENCE’s 2022 story on religiosity and respecting other’s spiritual practices here.

Popular lore surrounding the notorious Salem witch trials brings to mind images of white women and girls being harmed for their perceived witchcraft, which is true. However, of the 100 people persecuted, killed, or both during the trial, which lasted from the spring of 1692 until May 1693, majority of them were Black. This has directly impacted how Black witches have been perceived in America and has contributed to misunderstandings about non-white spiritual practices.

“One of the earliest stories of the trials non-white witches in America face is that of Tituba, an enslaved indigenous woman commonly referred to as ‘the Black Witch of Salem.’”

A report in academic journal The North Star reveals that during the 1620s and even before, throughout the Americas and Europe, Black witches were depicted as dark, evil beings, with strong ties to the devil.

“Early modern Europe already had long-standing discourses that associated Africans peoples and the devil, and many Spanish traditions, both elite and popular, linked dark skin with the devil,” writes Heather R White. “Witches tried in Logroño, Spain, testified that the devil appeared as “a dark-skinned man with wide, glaring horrible eyes.” The tradition of representing evil with the color black developed with the frequent portrayal of the devil as a [B]lack man in Spanish medieval art.”

Black women often had been convicted for crimes like arson or murder, and faced much harsher punishment that their white couterparts accused of the same crimes. Nearly 87 percent of the women executed from 1608 to 2002, were Black, according to the Espy File on U.S. executions.

One of the earliest stories of the trials non-white witches in America face is that of Tituba, an enslaved indigenous woman commonly referred to as “the Black Witch of Salem.” Early drawings depict her as a dark, terrifying creature. She would later be accused of making a group of young girls, including her slave owner Samuel Parris’ daughter, Betty, and his niece, Abigail, bark like dogs and contort their bodies.

Learn more about Tituba’s story here.

While it has not been made clear if these allegations were true, we do know that anytime a woman, particularly a woman of color, chooses to live out the framework of Christianity, she is labeled as an agent of the devil and must be destroyed. Hollywood only exacerbated these tropes by showing constant barrages of unattractive, evil, green (or otherwise dark skinned) women with broomsticks like the Wicked Witch of the East character from the Wizard of Oz.

Throughout the film, she was juxtaposed against Glenda the Good Witch, an attractive, blond-haired, blue-eyed white woman who was revered for her kindness and wisdom.

Glenda’s treatment seems to be the status quo for white women in shows like Bewitched, Sabrina The Teenage Witch, Charmed and other media centered on white womanhood. They were allowed a certain amount of humanity and vulnerability inaccessible to Black women, in the real world. Not surprisingly, along with being wildly popular, the shows clearly lacked representation of Black characters, even when explicitly referring to Salem witch trials.

One of the expectations was 1996’s The Craft, with Rachel True’s character Rochelle, but True would later admit she faced discrimination both on and off screen.

Still, Spalter notes while Hollywood has gotten many things wrong, there are a few things that it has gotten right. In recent years, there has been an influx of diverse characters on popular television shows like American Horror Story: Coven and The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina and the conversation is starting to change.

“I think that has a lot to do with people doing much better research when they write their fictional witches,” Spalter says.

Thee media usually portrays witchcraft as this dark power often harnessed to exact revenge on those who harmed you, but in fact, most craft isn’t used for hexes but for self-improvement, money magic, finding direction in life, and more, according to Paula Alexis, another witch and wellness program coordinator based in Canada.

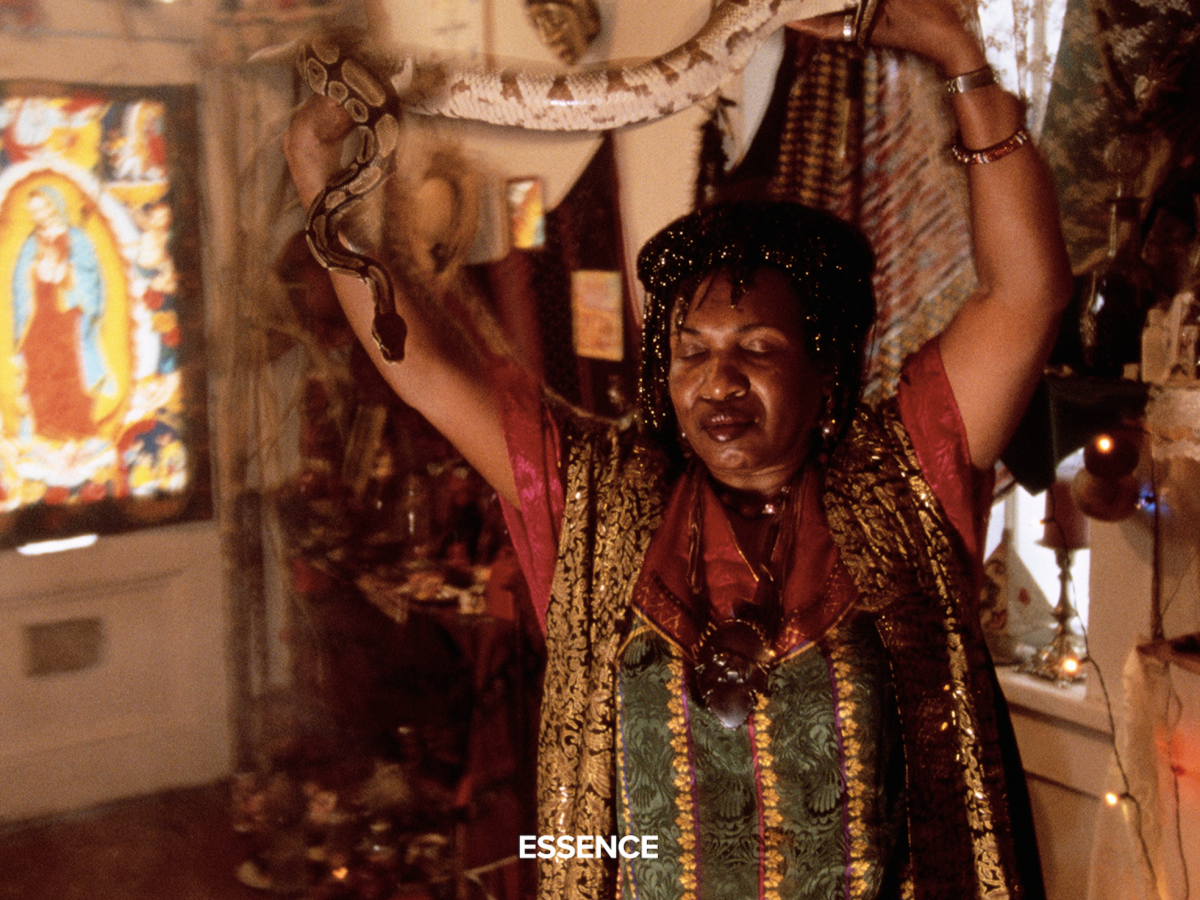

Traditionally (and before the Salem witch trials), Black witches served as healers, midwives, cooks, and more.

“If anything bad happened to these enslavers, they would blame the Black or Indigenous witch and send her to be “judged,” but often just killed,” Alexis says. “White women not protecting these women from being killed for being an evil witch hunt found themselves next in line when white men expanded their misogynist crusade. Many believed they would be safe because of their skin color, but that didn’t go well.”

“They were left out of the history books because servants and slaves only get to be in history books when pivital to the victor.”

Fellow practitioner, writer, and ancestral healer JuJu Bae agrees that while the media is slowly changing, there are many widespread, false tropes For one, Hollywood often portrays the practice of Wicca as the core of witchcraft, when in reality, the pagan religion is just one of the many offshoots of witchcraft. It has typically been performed by white women.

“The media has gotten a lot of things wrong when it comes to spirituality, particularly the spiritual systems of Black people that are outside of the Abrahamic traditions,” Bae says.

Bae also notes that Black witches, particularly those who study traditional African practices like Hoodoo and Vodun, experience rampant anti-Blackness even inside their respective communities. “I think it’s really interesting when you see people who practice, particularly Black people who practice conjure or a craft. It’s always demonic and evil. But that’s not a new concept,” she says.

All three women highlighted that the history of Black witches is often forgotten because many enslaved women who practiced witchcraft were unfortunately merely stepping stones for many white witches and crusaders. “They were left out of the history books because servants and slaves only get to be in history books when pivotal to the victor,” Alexis says. For decades, rampant anti-Blackness and misogynoir made it nearly impossible for Black witches to receive not only accurate, but sympathetic, representation on screen.

Today, with the help of more Black showrunners and creators being given power to create more diverse stories, the narrative is starting to shift, leading to the creation of television shows like Juju (which is reminiscent of Charmed), which debuted in 2019 via Amazon Prime. The web series thrives on writing authentic Black characters in genuine ways that resonate more with Black people tuning in and less with caring about the idea of white acceptance.

“It’s so Black. Even in the little roles, like being an extra in the restaurant or the work best friend like Jama in Episode 2,” creator Moon Ferguson told Variety. “She’s the work best friend, but it’s not like she’s the token Black girl, best friend to boost and uplift her white coworker. It’s literally just a sisterhood within the workplace.”

While Hollywood is getting better, there is still much work that needs to be done by society at large. The misconceptions about Black witches directly result from the white patriarchal religious indoctrination that has slowly seeped into the cultural zeitgeist, showing up in the representation that we see on screen. For the narrative to truly change, the idea of juxtaposing witchcraft, particularly witchcraft performed by Black women, with evilness and the devil will have to be completely unrooted. Black witches deserve to be portrayed for exactly what they are—human beings.