Amid our current civil rights movement and a tumultuous year that has brought forth a great deal of struggle and hardship, Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson has given us a gift. With his directorial debut Summer of Soul (… Or When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), he has unearthed an aspect of Black history that won’t soon be forgotten.

The year 1969 was pivotal for Black people. While much of the world was concerned with getting the first man on the moon, the Black community was focused inward, still reeling from a turbulent decade that stole the lives of Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr., and countless others. It was the final year of a decade marked by chaos, violence, and determination. It was also the year we shed the word negro and became Black.

While much of the nation was turned toward Woodstock, that same summer in Harlem, Tony Lawrence, a charismatic singer, and hustler, put on his third cultural festival in collaboration with the NYC Parks Department. The Harlem Cultural Festival of 1969 would be his most significant. The heroin epidemic had ravaged Harlem, and the community was rocked by riots following Dr. King’s assassination. With the help of the Black Panthers, who acted as security, and with the support of then-New York Mayor John Lindsay, what Lawrence pulled off that summer was a vibrant celebration of Blackness, pride, and healing.

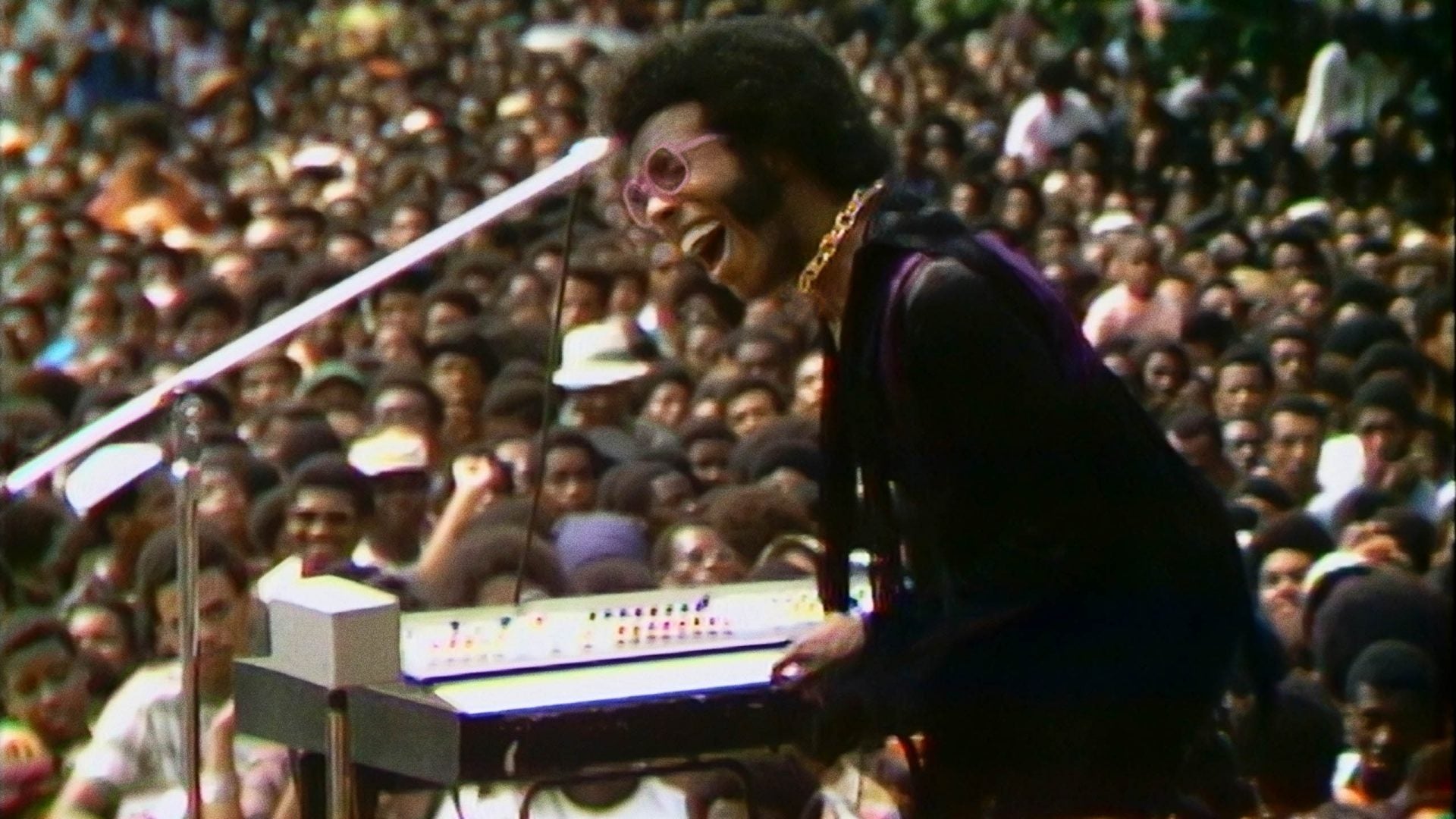

More than 300,000 people attended the Harlem Cultural Festival in the six weeks that it ran. Lawrence brought a multitude of acts on stage, including Sly and the Family Stone, a newly solo David Ruffin, and Nina Simone. However, after the final day of the festival, when the debris at Mt. Morris Park was swept away, and the stage was dismantled, it was as if nothing had happened.

For the past 50 years, the Harlem Cultural Festival has lived on only in the attendees’ memories. These were the young people who rushed toward the park each weekend eager to see musicians like B.B. King, The 5th Dimension, and Stevie Wonder. With Thompson capturing their stories and memories in interviews, it’s astonishing that they recall the smallest details as if the festival happened yesterday.

A musical legend himself, Thompson has an intricate understanding of the medium and the impact that it has had on Black culture. While there are snippets of other acts from the festival like the iconic Moms Mabley and even a glimpse of Red Foxx in the film, the music is the centerpiece. Like a seasoned filmmaker, Thompson expands on the impact of various genres, from gospel to Blues and Motown, and how they pushed the community forward when so much had been lost. His placement of Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staple’s performance of “Precious Lord” stands almost as the film’s crowning jewel.

However, Thompson is careful to expand his story beyond just the music. The attendees and a clear understanding of what it took for Lawrence to get the festival made are just as important here. With little money or guarantees, Lawrence worked diligently to get megastars to participate. He had to get creative, carefully placing the stage toward the sun since he couldn’t afford lights and asking the Panthers to step in when the NYPD initially refused to provide security. Lawrence was on stage each day of the festival, dressed in vibrant colors and acting the MC, introducing performers and speaking to the massive crowds.

The extensive camera crew that Lawrence brought in, directed by filmmaker Hal Tulchin, shows just how immense this undertaking must have been. The camera sweeps back and forth over brown faces of all different hues; some dressed in the conservative wear of the ’60s and others leaning toward a new decade, donning bell bottoms and large Afros —everyone waving eagerly into the camera lens. You can almost smell the Afro sheen and fried chicken that Harlem legend Musa Jackson remembers lingering in the air.

Using archival footage of the ’60s, maps of Harlem, old interviews from Harlemites, and sifting through over 40 hours of festival footage, Thompson fleshes out the world that was buzzing around the Harlem Cultural Festival, which allowed it to evolve into the historical moment that it became. Summer of Soul also provides a through-line connection to what’s happening today amid the Black Lives Matter movement and our continued fight for justice.

Though Tulchi’s footage had been buried deep in a basement somewhere for the past five decades after he was unable to sell it, Summer of Soul is pristine, delivering ripe audio and visuals, as if the viewer is standing in the park jamming with Stevie or listening to the Reverend Jessie Jackson describe Dr. King’s final moments.

Though Thompson never dwells on why Tulchin was never able to sell the footage or how he discovered it, this “Questlove Jawn,” as it’s described in the opening credits, has brought forth the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival at the exact right time. It’s both a balm and a reminder that we are here and real and beautiful. It is yet another rare jewel in Black history that we will be able to hold close to our hearts from this moment on.

Summer of Soul (… Or When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) premiered at Sundance Film Festival, Jan. 28, 2021.