In 1860 on the eve of the American Civil War and 52 years after the international slave trade was outlawed in the U.S., 110 African men, women, and children arrived on the shores of Alabama in a ship called Clotilda. The captives were sold to various plantations, and the vessel was set ablaze by Timothy Meaher, the man who had chartered the illegal expedition.

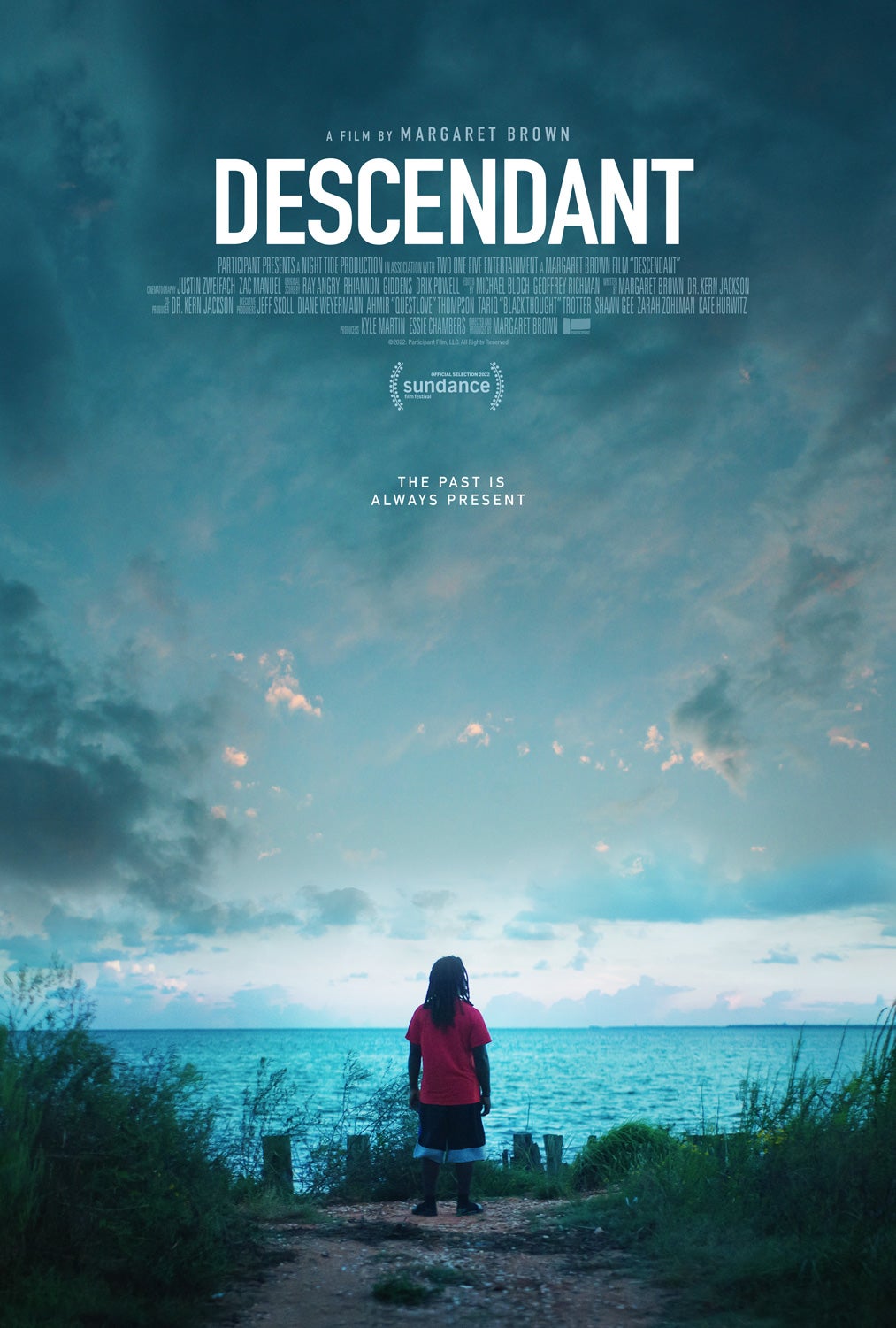

One hundred sixty-two years later, filmmaker Margaret Brown has turned her lens toward the descendants of Clotilda’s survivors in her captivating documentary film Descendant. The story of the Clotilda has always been alive and well amongst the descendants of the ship’s survivors. Many of them still call Africatown, Alabama – founded in 1866 by the formally enslaved – home. When the ship’s wreckage was found in 2019, the world began to pay attention. But as Brown’s film suggests, many more questions still arise.

Amid the debut of Descendant at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival, ESSENCE spoke with Brown, Joycelyn Davis, a direct descendant of one of the captured African men, Oluale, and Kamau Sadiki, a diver working with the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) Slave Wrecks Project. We spoke about the myth surrounding Clotilda, who shapes history, and what should happen next.

“These enslaved Africans were documented,” Davis said about the “legend” of the Clotilda. “They gained citizenship, and they were in Captain [William] Foster’s log, so I could never understand the myth, and I think some people needed something tangible like the ship itself to make the story real. I remember as far back as a child, six or seven years old hearing about the story.”

Brown’s entry point into Clotilda came while working on a very different story. Her 2008 documentary The Order of Myths was centered on the racially segregated Mardi Gras celebrations in her hometown of Mobile. “At that time, I had heard that Helen Meaher, the white Mardi Gras queen that year, was descended from this family that brought the last enslaved people into the country,” she explained. “White people kind of gossip about that. Stephanie Lucas was the Black Mardi Gras queen. I was at her house with her grandparents when her grandfather very casually said, ‘Oh, our family descended off that ship.’ When they thought they had found the Clotilda, it was a year and a half before they found the real ship, and people were writing me on my social media saying, “You really should come back to Mobile.’ The ship harnesses potential DNA evidence, and that harnesses emotional memory. It’s a sacred site of people’s ancestors. This is something so unique to American history, and the power of that is I think immeasurable, and I think the community felt that immediately.”

Many people are focused on the Clotilda itself, but there is so much more at stake for Davis. “My focus is not so much on the ship,” she explained. “It’s preserving the history and doing things in the community, economic growth, and those type of things. So, I’m excited about Kamau and his team finding the ship. It’s great. It’s made national news, but I’m just so into my ancestors. You can see the physical area and space where Africans were captured and brought to these shores, so that’s very powerful. However, the focus always has to be on the people of Africatown.”

Africatown is still very much a close-knit community, but it’s boxed in by land owned by the state of Alabama and the Meaher family, whose ancestors charted the illegal ship. Many parts of the town have been zoned for various toxic industries that have literally poisoned the community. Looking forward, both Davis and Sadiki want justice. “Justice can mean so many different things,” Davis reflected. “We know that the Meahers did not enslave all of those enslaved Africans. They were dispersed to different places. Justice to me looks like bringing forth everyone who was involved. I want everybody at the table. That’s just a dream of mine because Colonel Thomas Buford enslaved my ancestor, and I would love to meet that family. I want to learn some history about how they met the Meaher family. As far as the Meaher family, they could put some dollars into the community and leave the community. They still own half of Africatown to this day, there are streets named after them, there are streets named after their children, and so, that stain that they left is still here.”

In making the film, Brown faced many roadblocks with some of the “powers at be” in Mobile. “I think the community was very excited by the truth and some reconciliation or justice that could potentially come about with this,” she said. “I remember being in that room that day, and there were certain parties that tried to keep us out of that room and control the story.”

While people like Sadiki, Davis, and her family and family historian Lorna Woods worked tirelessly to keep the narrative of the Clotilda weaved into the fabric of Africatown, others tried to suppress it and keep it buried underneath the murky waters of the northern Gulf Coast. However, the truth can never truly be washed away.

“It’s just a question of how long it’s going to lay undiscovered; laden out of the consciousness of the public, Sadiki says. “I’ll put it more bluntly, the systematic annihilation of individual memory and heritage and culture, particularly as it relates to Black bodies that suffer so tremendously under the African slave trade. But the more that we bring these artifacts forward, the more we add to the narrative of our stories and bring back into memory those stories that have been suppressed.”

Despite finding Clotilda and the attention brought to Africatown, there is still so much to unpack, and many truths remain buried. “There’s stuff happening with zoning and the discovery daily,” Brown explained. “This movie is a drop in the bucket of a collective history. This story continues, and it started a long time ago. I hope this film becomes part of this larger conversation that’s been going on for a long time. I think that there will always be attempts to hide truths because it’s about power. But the Africatown residents never let go of their history.”

Descendant certainly isn’t the first time Clotilda has been pushed into the foreground of society. Emma Langdon Roch was the first to publish a book based on interviews with Cudjoe Lewis, the last known adult survivor of the transatlantic slave trade, in 1914’s Sketches of the South. There is also Natalie Robertson’s The Slave Ship Clotilda and the Making of Africatown, USA: Spirit of Our Ancestors. Zora Neale Hurston’s Barracoon: The Story of the Last “Black Cargo” was written in 1927 and finally published in 2018. Most recently, Ben Raies’ The Last Slave Ship hit bookshelves.

Davis has made it her duty to preserve her legacy. “We have something tangible that we can touch, and then also, we have those individuals in Africatown and with the film and everything where it’s going to be spread globally. You can’t erase it,” she said. “We are the keepers of this. So, I won’t let it be erased.”

Netflix has acquired the worldwide rights to Descendant, which premiered at Sundance Festival January 22, and it will debut on the streaming platform later this year.