In the opening scenes of Joe Brewster and Michèle Stephenson’s documentary on the revolutionary poet Nikki Giovanni, the subject of the doc reminds us in a scene taken from her 2019 conversation with American anthropologist Dr. Johnnetta B. Cole at the Apollo Theater that she is “polite but not friendly.” Perhaps there is no better characterization of the poet who throughout the documentary maintains an air of only revealing about herself what she wishes to be known.

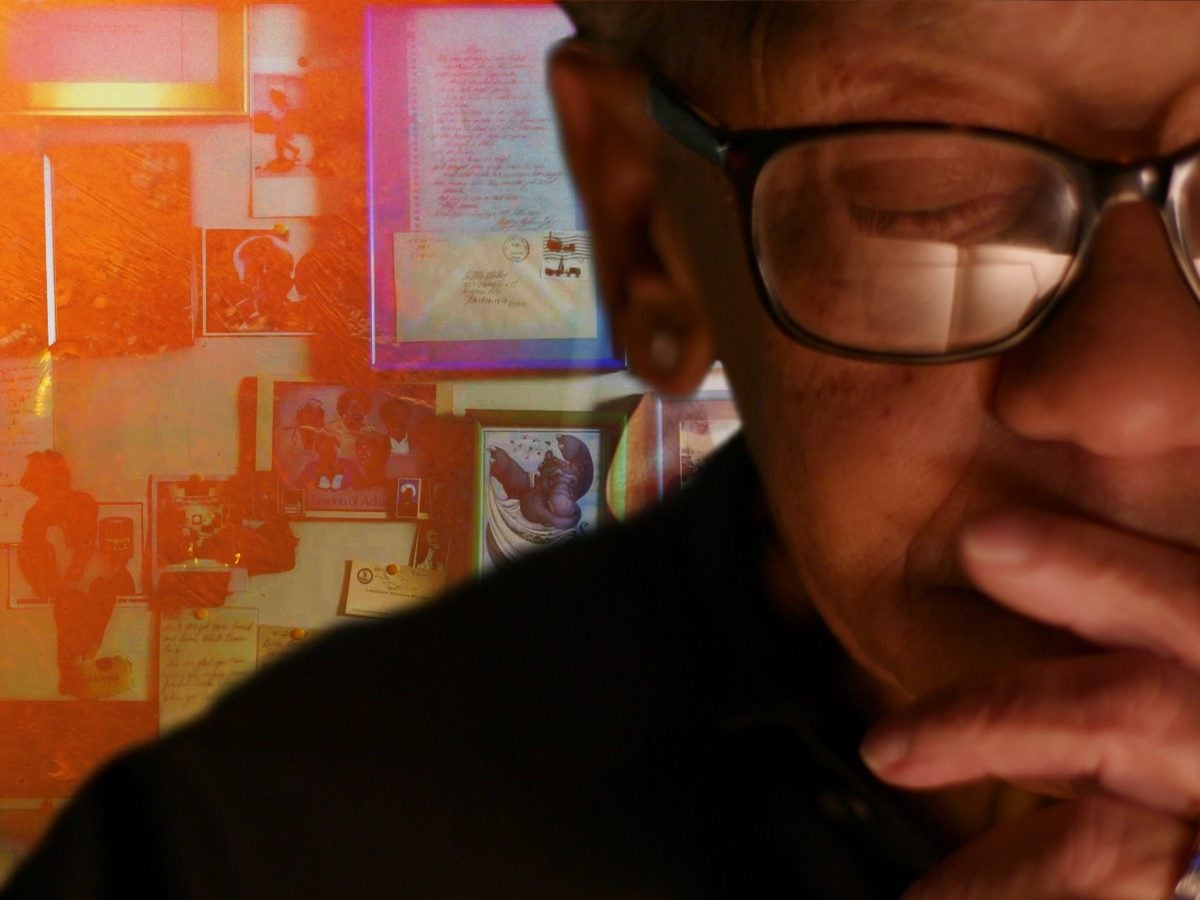

Giovanni, who says in the documentary, Going to Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project, which made its debut at Sundance January 20, that she remembers only what she wants to remember and makes everything else up, appears to thoroughly live up to that phrase. Giving accounts of her life in present day, there are shots of Giovanni, an extraordinary writer and thinker, living an ordinary life in her mid-70s: planting things, visiting with family and friends, taking medication, and talking about a surgery she had or another that she plans to have. Make no mistake however, that Giovanni is contemplating heavily on her mortality any more now than she did ever. From her retelling of her life and her present state, she seems to be acutely aware of death and even has a certain kind of embrace of it that is rare.

Indeed, Giovanni sort of sees death as transition, a sort of accompanying perspective she has adopted in her preoccupation with space, the planets, and in particular, Mars. In her love of the idea of going to space, Giovanni prioritizes that it is Black women who should be asked to go there first as she believes that we are the most transcendent beings on earth. In her descriptions of her prioritizations of Black women, Giovanni is unequivocal in her love of self and sisters. And yet, there seems to have been lacking from the documentary any interrogation of the idea that a transition from Earth to Mars may bring a conflict of conquering, colonizing a place that perhaps isn’t ours to be in, much as Giovanni says she would like to make her final transition in space.

Also lacking in the documentary were interrogations of Giovanni’s positions on apartheid South Africa and why she deemed the resistance to it — those protesting in the United States on behalf of Black South Africans — as one that came from an elite basis and not from the common person. The lack of interrogation leaves a space in which the implications of the push back she received is not really explicitly discussed.

In any case, that may of course be less of a directional choice on the part of Brewster and Stephenson and may yet again be the outcome of trying to make a documentary about a poet, a writer, a woman who so unapologetically only tells you what she wants you want to know, and leaves you wondering about the rest, almost as if to remind you that she gives what she gives in her work — love, protest, encouragement, history, retellings, and the rest of it is her business.

Apart from shots of Giovanni with her family and loved ones, those of her transiting by bus, by train, by plane — metaphors for moving between spaces, real, imagined, and futuristic — the most evoking scenes are the ones where she is reading poetry, demanding the nation reckon with itself, and that her people and herself do the same, as well as the famed conversation with her dear friend and fellow icon James Baldwin in the SOUL! Program recorded in 1971.

In the end, the documentary, shot beautifully and honestly, could only be as revealing as the subject and Giovanni gives us what she gives us and leaves us to make up the rest of the story for ourselves.