In Lisa Cortés’ profound portrayal of Little Richard, born Richard Wayne Penniman, the artist is first and foremost, a son of Macon, Georgia, born to a large family, faith at the forefront of how he was raised, with the background sound of his childhood, blues music. In the film, which includes many voices from The Rolling Stones’ Mick Jagger whom Richard influenced, music historians and scholars, and even some of the late artist’s cousins, friends, and former band mates — Richard is painted as a knowing, confident pioneer of the rock ‘n’roll music whose relationship to his Christian faith and his queerness were at times in conflict to himself.

As the documentary oscillates between interviews from the artist himself throughout his career, as well as old footage of his concerts and audio and visual commentary from friends, music colleagues, and culture commentators, the visual aesthetic of the film at times becomes other worldly, often including scenes of the natural world in all its glory from ocean waves hitting shore to flowers opening and closing.

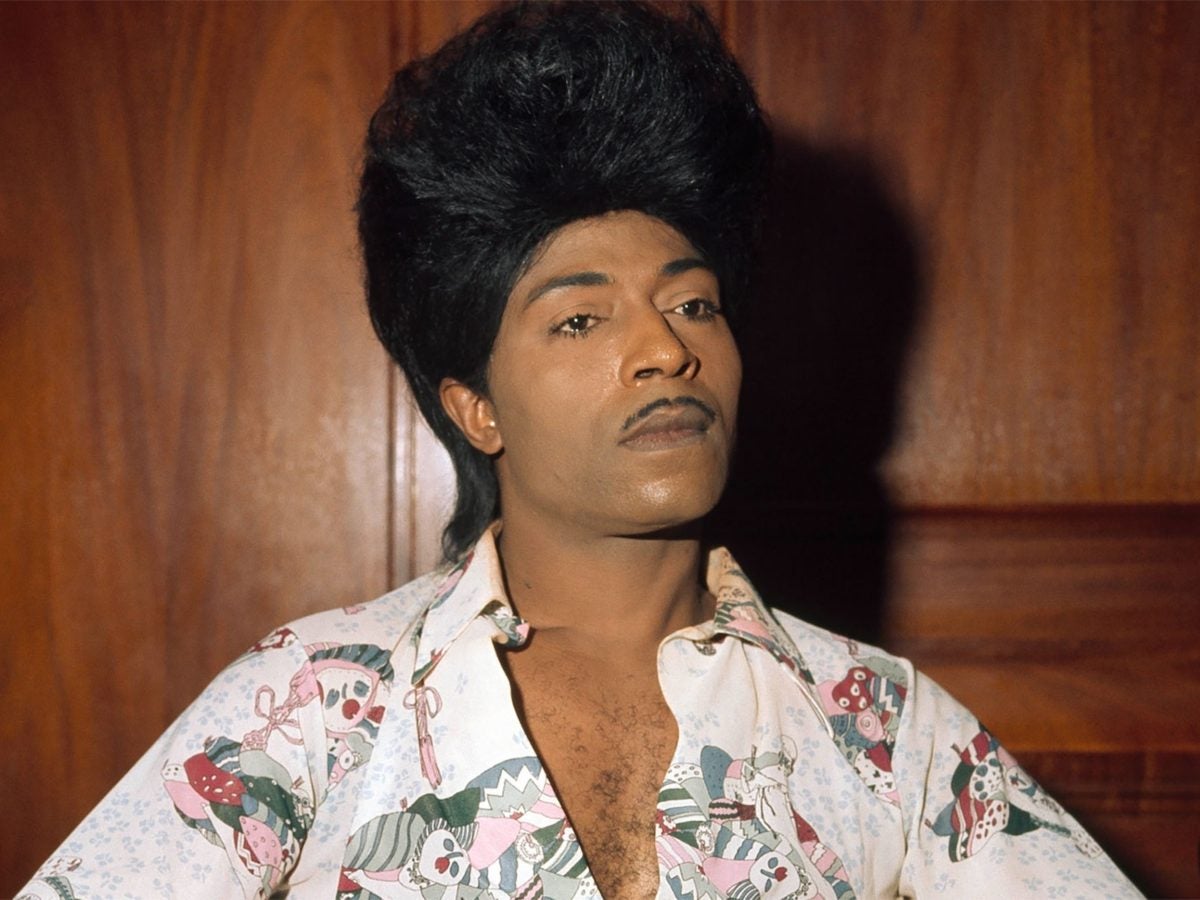

As depicted in the film, Richard was an artist who didn’t believe in false modesty. He understood his own greatness and in so doing, could see the greatness in others, and especially those who, like him, existed outside of a white, straight, normative experience. From an early age, he loved to present his queerness in attire and beautifying himself, and throughout his life would waver between understanding himself as an openly gay or queer person — and yet, also running away from the identity, perhaps as a way to protect himself from what he thought of as a conflict with the faith he practiced, and that was dear to him throughout his life.

His identity as queer however couldn’t be divorced from his music and how he performed that music as a pioneer of the rock ‘n’ roll genre. Indeed, he rightly called himself the king of it and the film makes it apparent that this sound cannot but be contextualized in a space that is both Black and queer at its root, like the artist himself. Of course, Richard had his influences such as the great godmother of rock, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, as well as fellow Black, queer icons Billy Wright and Esquerita. But the documentary also makes clear that while there were co-pioneers of the genre such as Chuck Berry — there were also musical “sons” of the artist from Prince to David Bowie, and even The Beatles would not be The Beatles without Richard.

The documentary also touched on the cultural appropriation that is an outcome of Black musical history and pop culture in the country, and the implications both in cultural memory and monetarily for Black artists. Richard is shown as being aware of not only his greatness but of how white artists were brought to the fore on the culture on his back, and it would show him both in jest and seriously, demand that he be recognized for his contributions. In an American Music Awards ceremony in 1997 when he finally was awarded the Merit Award, the artist’s tears are a confession of his desire to finally be seen for what he did in music.

Altogether, the film doesn’t shy away from Richard’s public and personal life, including his openness on sex and sexuality, and the self-wrangling the life of a Black, rock ‘n’ roll star embodied alongside this person of faith, all contextualized within the backdrop of becoming who and what he was in a racist, queerantagonistic society. In the final analysis, the documentary while at times goes quite quickly through his public and personal phases such as his periods performing gospel or the drug scene he was a part of and that took the lives of those closest to him, Cortés still offers an authentic look at someone who was a kind of Moses of sorts in his music life and queer presentation — making a way for others even where he sometimes struggled to make a way for himself.

One is left feeling, perhaps hoping that when Richard died in 2020 that he was truly at peace with all the shapes and side of himself embodying the words of scholar and writer, Dr. Zandria Robinson, who said of the artist in the film, “I know he knows when he is fully himself, he is closest to God.”