It was Saturday night on Broadway, and I had just twirled myself into the wings at the end of the first big number in Act 1 about becoming a woman (as imagined by—surprise!—white, straight, cisgender male writers). I took my featured role as Donna Summer, our beloved disco queen, very seriously. I strived to replicate her aura with my technique, my stage presence, and by working a heavy, voluminous feathered-and-flipped wig.

Each time I moved through the costume change after the feature, I always had a really bad attitude. The attitude, appearing seemingly out of nowhere, always showed up at the same time and in the same place: the wig room.

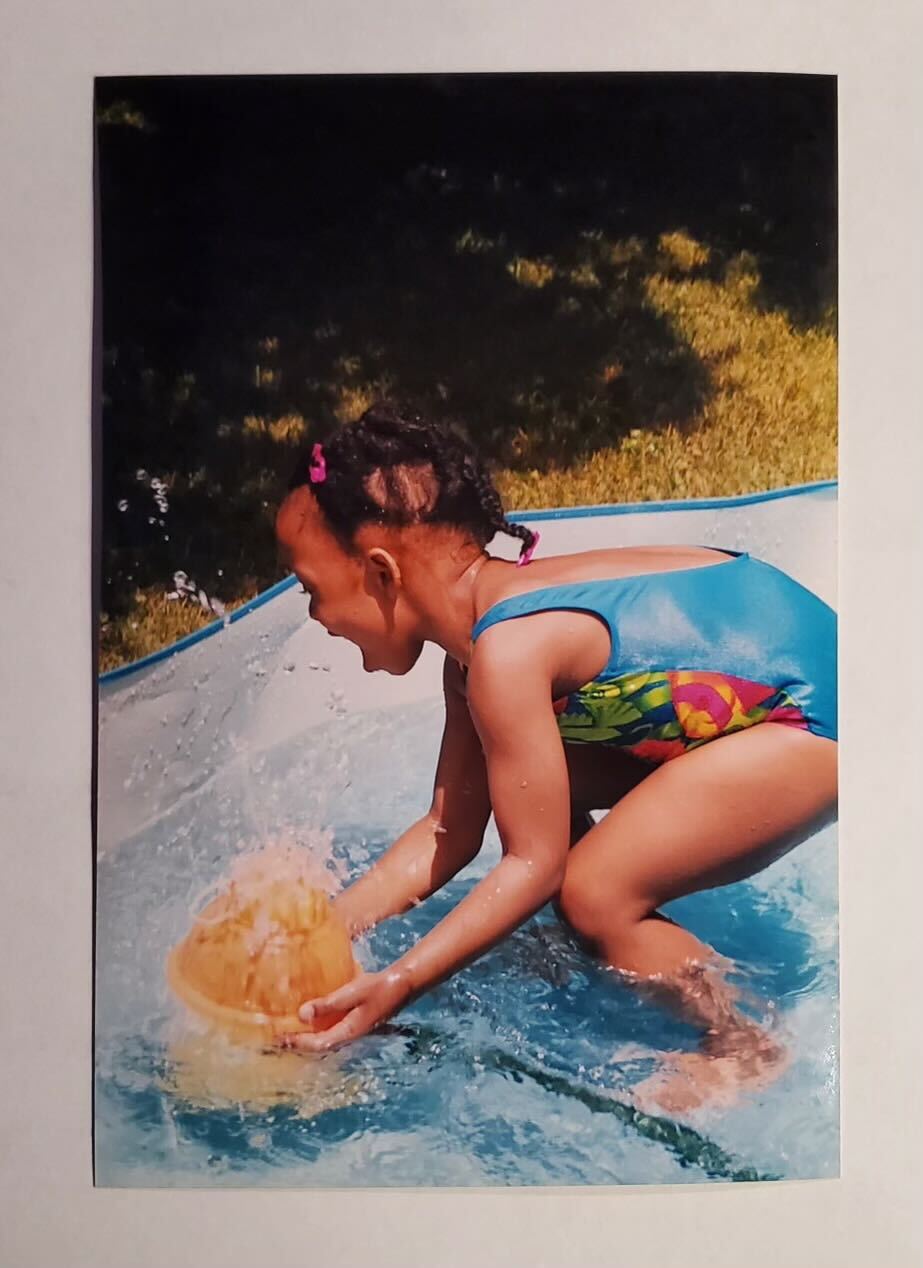

Growing up as a little Black girl with alopecia on the southside of Chicago at the beginning of the millennium, rooms full of wigs were glimpses into what I imagined heaven to be like. Gorgeous, goddess-like wigged women on window wrap posters would welcome me into beauty supply houses, each with a warm “smize” as uniquely textured as their hair. I’d wander away from whichever woman of the house I tagged along with to frolic between the fragrant aisles of oils, styling gels, and relaxer kits toward the back, where the wigs were.

There, the floors and walls would be lined with rows of styrofoam figureheads that fashion themselves into an altar of Black beauty. I would stand with my widening bald spots, receding hairline, and overwhelming exhilaration amidst the heavenly choir of plastic busts that sing the gospels of beauty to me. Each wig in the room would perform a unique tune that would drown out the echoing sounds of the little Black girls in my grade who would bully me about my alopecia.

By high school, my mama and aunties became my tagalongs to those wig rooms, encouraging me to define my own beauty. As a fledgling artiste, this meant making a spectacle of my condition as self-defense: wearing funky (sometimes questionable!) wigs with shocking textures, intimidating colors, and elaborate styles. Just as my peers’ eyes began adjusting to one look, I’d spin the block with a whole new do. My wigs started talking back. The creativity and pubescent angst I alchemized with those wigs empowered me to shave off what was left of my natural hair underneath them, knowing it wouldn’t grow back.

I moved to New York as an upperclassman at NYU and started making friends among my artsy peers who all had unique aesthetic expressions and validated my own. It finally felt normal to escape uptown after class and spend hours in Harlem beauty supply wig rooms, plucking baby hairs off of whichever lace wig caught my eye that week. For the first time, I felt like I blended in, and I owed that sense of acceptance to those wig rooms I grew up in.

But for the first time in my life, on that Saturday night on Broadway, at that point in my show (much like that point in each of the shows I’d performed in before), in that salon chair, in that wig room— an attitude snuck up on me. And a really bad one at that.

The skillful wig tech efficiently fished through my mountains of waves for strategically camouflaged hairpins and delicately removed them and the wig. I overheard dialogue from the farce scene happening onstage over the loudspeaker, and the “comedic” bit revved up to a joke with a one-word punchline— an answer to a question in a complete sentence:

“Alopecia.”

It was always followed by faint, meek-bodied laughter. I thought these speakers are supposed to tell me where we are in the show, not call me a ‘bald-headed hoe’, I thought to myself with disgust. I choked on a triggered chuckle with the rest of the underwhelmed audience as I stared at my bald head and beat face in the mirror.

I knew why I was straining to laugh. Does anyone else?

Cracking farcical jokes about alopecia is ableist misogynoir at its finest. As an autoimmune disorder that causes hair loss, alopecia is not simply an aesthetic difference; it is a disability, particularly in a social context, and one that disproportionately affects Black women and femmes.

As the sound waves from the infamous 2022 Oscars “slap-heard-round-the-world” rippled through our community, I had a virtual exchange with one of my heroes, Sonya Renee Taylor, a consequential leader and writer who is also a Black woman with alopecia. Following her astute analysis on social media of the trauma that contributed to both Chris Rock’s violent gibe on Jada Pinkett’s alopecia and Will Smith’s violent slap in response, I felt compelled to ask Sonya about her inclusion of ableism in the discussion— defensive about my difference being labeled a disability.

In response, Taylor brilliantly offered, “Disorders and diseases are often disabling and using the social definition of disability, one is disabled by a society that is organized to exclude or marginalize them based on a condition or circumstance deemed non-normative. So in a society that deems hair as normative, as tied to femininity, and tied to access and privilege, not having hair would be disabling.”

Upon digging deeper into disability justice frameworks and my lived experience, I know now that alopecia deserves advocacy as a disability because it is a clinical difference that contributes to our social marginalization. Jokes about alopecia are always dusty anyway because making fun of people’s bodies is never appropriate. Period. The ableism of those jokes adds a layer of dustiness. And when it comes to Black girls and femmes with alopecia, yet another layer of dust settles deeper into its connotation of misogynoir.

Black women and femmes have the highest rates of alopecia globally. A 2016 study of about 5,600 Black women found that nearly half experienced hair loss. More Black, Latinx, and Asian women have alopecia areata, or bald patches in the scalp and face, compared to white women. The American Academy of Dermatology found that the number one cause of hair loss in Black women is central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), primarily affecting those with darker skin tones. What sets us apart from other demographics is that 1 in 3 Black women experience traction alopecia, which develops from prolonged pulling and stretching of the hair. I hesitate to label this as “self-inflicted,” as these styles can be driven by societal pressure to conform to beauty standards.

That may not be the only societal strain that contributes to our statistics. I’m sure many of our genetic diagnoses are linked to cultural histories of systemic abuse and trauma. I recently saw a video of a young girl from Gaza, distraught as the stress from the terror of the bombardment caused her to lose everything, including her hair. It deepened my solidarity as it reminded me of the parallel impact that oppressive societal circumstances have had on Black femme bodies, turning physiological stress responses into trauma genes that are passed down through generations. Unfortunately, the erasure of these generational histories and clinical cases in the diaspora make this hard to study.

I find our statistics ironic since most of the violence I’ve faced as a Black girl with alopecia has been by the hands of other Black girls. Growing up in predominantly Black environments makes this experience less miraculous, and the concept of being an object of their projections of internalized misogyny and anti-Blackness doesn’t challenge me; we are all conditioned in internalized misogynoir.

What is curious to me is that, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve noticed that many grown folks never grew out of keeping the consequence of my disorder—specifically being “bald headed”—out of their mouths. What a strange insult… what is merely an observational fact is so often used amongst women as a punchline to a parable— a quip to strip someone of good character, or a boring, easy label of disgust. Why are the girls so pressed by my baldness? Why are we all so scared of it?

I’m led to believe that Black women and femmes with alopecia aren’t the only ones affected by the disability. Maybe all Black women, especially those of us who are straight and cisgender, feel the threat. I think we are afraid that losing hair will lead to us losing ourselves, that we will be alienated from our Blackness, our femininity, and even our adulthood. We may also fear that less hair equates to less power, agency, and beauty. I was afraid of all of this, too… only until I started embracing being “bald-headed” in these streets.

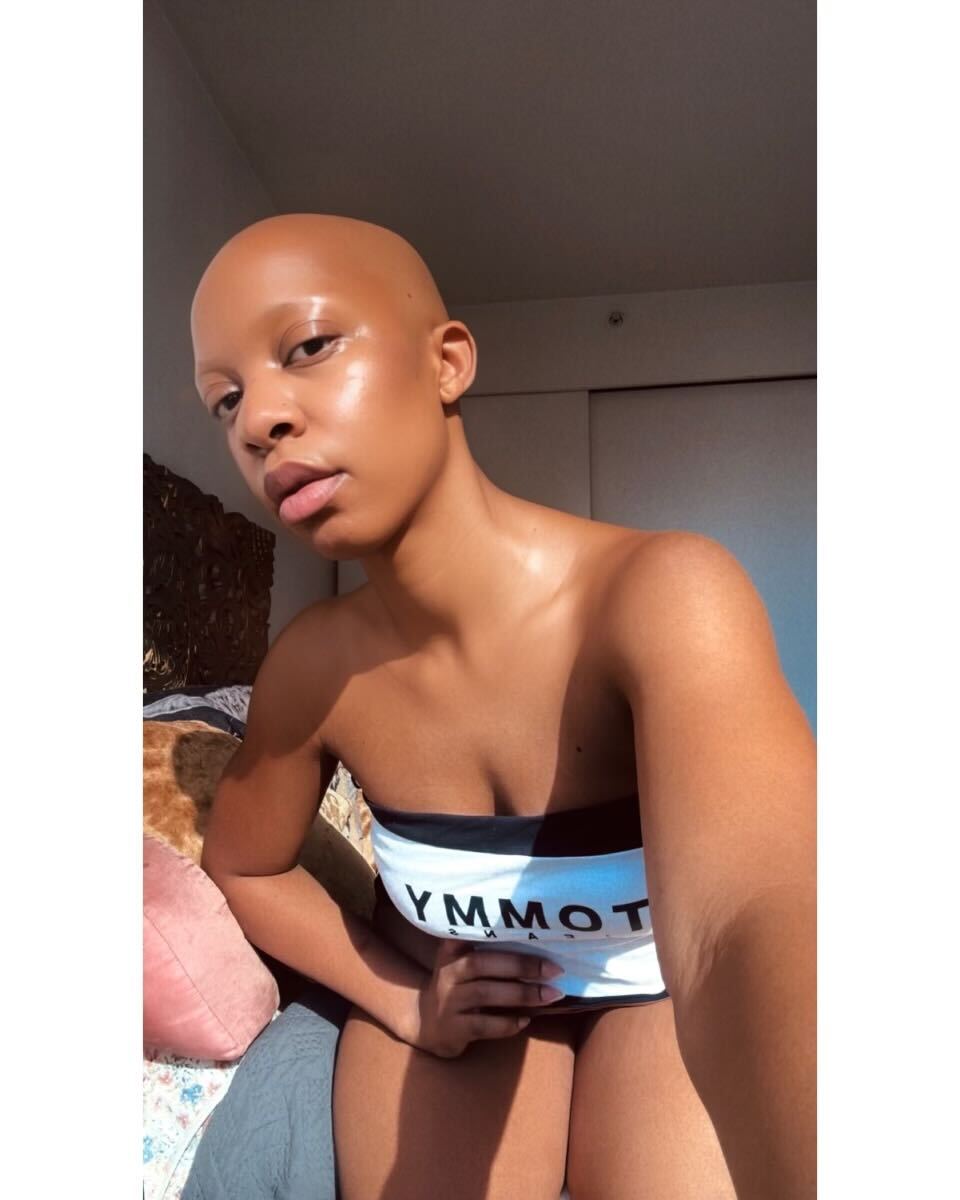

I stopped wearing wigs in public about a year into the pandemic as an experiment. Being publicly bald was unprecedented in all my 24 years. I rarely even entertained my baldness in private— sleeping with wigs to feel my “normal” girl fantasy and spending less time in the mirror to avoid body dysmorphia. The sides of my bald head were scarred, scabbed, and sometimes bloody from adhesives I used to blend the lace into my scalp—therefore blending my identity into beauty standards.

But as I was falling in love with my partner at the time, I was also falling in love with my nature, bald and all. I started by working on healing the injuries to my skin before concealing the discoloration from years of harm I had been inflicting on my scalp. It wasn’t until the time of my bald debut that I reflected on the fears and realities that had kept me from that moment all those years.

Because hair is a currency in Western capitalistic, white supremacist, colonialist, patriarchal beauty standards, whether in effect or in response, Black hair is also a currency by its own cultural standards. I noticed how natural hair subtly resurged with a raging vengeance during the Black Lives Matter Movement in 2013, and because I was already bald and wearing wigs at the time, I felt detached from my ability to participate in our collective expression of resistance.

It was my bald head that reminded me of traditions of baldness as a display of radical African femininity beyond colonial contexts. I learned about our people, like the Maasai women of Kenya and Tanzania, who shave their hair for spiritual traditions, invoking a newness and an initiation into their futures. I began to see my bald head as a reflection of the futurism that has always lived in my art, philosophy, and self-expression. This seeded in me a strong sense of belonging to a diaspora of women who represent the timelessness of feminine African legacies.

I think straight, cisgender women are most terrified of baldness. I think we are the most obsessed with femininity and with how people, particularly men, perceive our hair as tied to it. I don’t blame us entirely. All Black women and femmes, including and especially trans, cis, non-binary, and gender non-conforming people, are so quick to be masculinized regardless of our hair, which justifies our subversion. However, my queer and gender non-conforming siblings teach me that the gendering of hair that society participates in—the cacophony of rules about what makes hair feminine or masculine or whatever else—is arbitrary anyway!

For instance, long hair is often considered a signature of a high-femme aesthetic, which is why I overcompensated with long wigs so much in my late teens. However, long hair can somehow also symbolize masculinity in various contexts (think: shaggy aesthetics, “man buns”, etc.). On the other hand, it tickles me that people assume hyper-masculinity in bald women and femmes because I’ve personally never felt more effeminate. My smooth bald skin makes me feel so soft, and less hair accentuates all my juicy curves! Because the rules are so made-up, we get to define what femininity and masculinity are for ourselves.

It’s also lost on me how maturity and adulthood can be called into question based on hair. I didn’t want to go bald publically after my first and last “big chop” at 15 because I didn’t think it was time. I felt like I lacked the strength, maturity, and independence that I associated with all the bald Black women I had ever known. Instead, I gravitated toward youthful wigs to maintain an image of “adolescent innocence.” In an abrupt shift of perspective, no one could have prepared me for the infantilization I’ve faced with my baldness since my late teens—the creepy rizz-chat lines from boys about not having hair anywhere.

As I take Blackness, femininity, and “being grown” out of its braid, I realize how much of our muliebrity has always been coiffed by the oppressive desires of white supremacist patriarchy. The male gaze can’t construct our identity complexes with hair because our identity doesn’t even have to be attached to our hair if we don’t want it to be. My Black muliebrity lives in the energy inside me and the energy that surrounds me. As I continue to decolonize how I think of my personal self-expression, I find my power, agency, and beauty in this energy, too.

I can’t cap: having alopecia is complicated. Sometimes I feel stripped of the ability to assert my subjectivity in this world, like I am denied access to the versatility of choice. Sometimes, I want the option to flip my hair in my haters’ faces, knowing that it’s au naturale. Other times, I want to grow it all out like it’s 1976 down there, or stick my pit hair to the patriarchy, or try Nair and lasers on my legs with the other girls. I want a reason to go to the salon. I want to be accepted. I want to be desired. I want to be included. I want to be normal. I want to be pretty.

But I may be getting recognized as something more substantial now. Wigs made me feel pretty—like I could blend in. The authenticity of my bald head not only stands out as a striking look but more importantly, it feels true to me. I feel like a walking art piece, a challenging one with which to grapple or fall in love. Or, perhaps I’m a simple canvas on which to project your own imagination— your dreams of what beauty could be.

It has been over three years that I’ve been bald full-time. The decades of discoloration have fully cleared, and I am married to my skin and scalp care routine. I rarely wear wigs now, only when working on a show. My community recognizes my baldness as an extension of my futuristic work as a creative literary (Piscean!) architect of the collective subconscious. The embodiment of all those loving interpretations of me with my bald head feels very right.

And as for that show I was in… I left for a new gig. The show closed shortly after.

My final stop to that wig room was a relief. I took off my wig along with my prep, the crochet cap that a Black female wig tech innovated for my bald head when I first started working professionally (thank you, Ms. Kelly). I scrubbed off my stage makeup to reapply a light beat before a much-needed night out.

As I left the stage door and started toward the train, a beautiful Black woman on 42nd street stopped me immediately, eyes wide and super excited to tell me that, “you are working that head girl! You must be a model or something… just gorgeous! Believe it or not, I’m bald like you under this wig I got on. But I could never have enough confidence to rock my bald head like you!”

“I know you could. Look at you! You are gorgeous, too.”

I kept pushing toward the train. Seems like alopecia is in after all. I chuckled, this time in the spirit of having the last laugh. I am a gorgeous Black girl with alopecia. And you are gorgeous, too. And you. And you. And so are you.