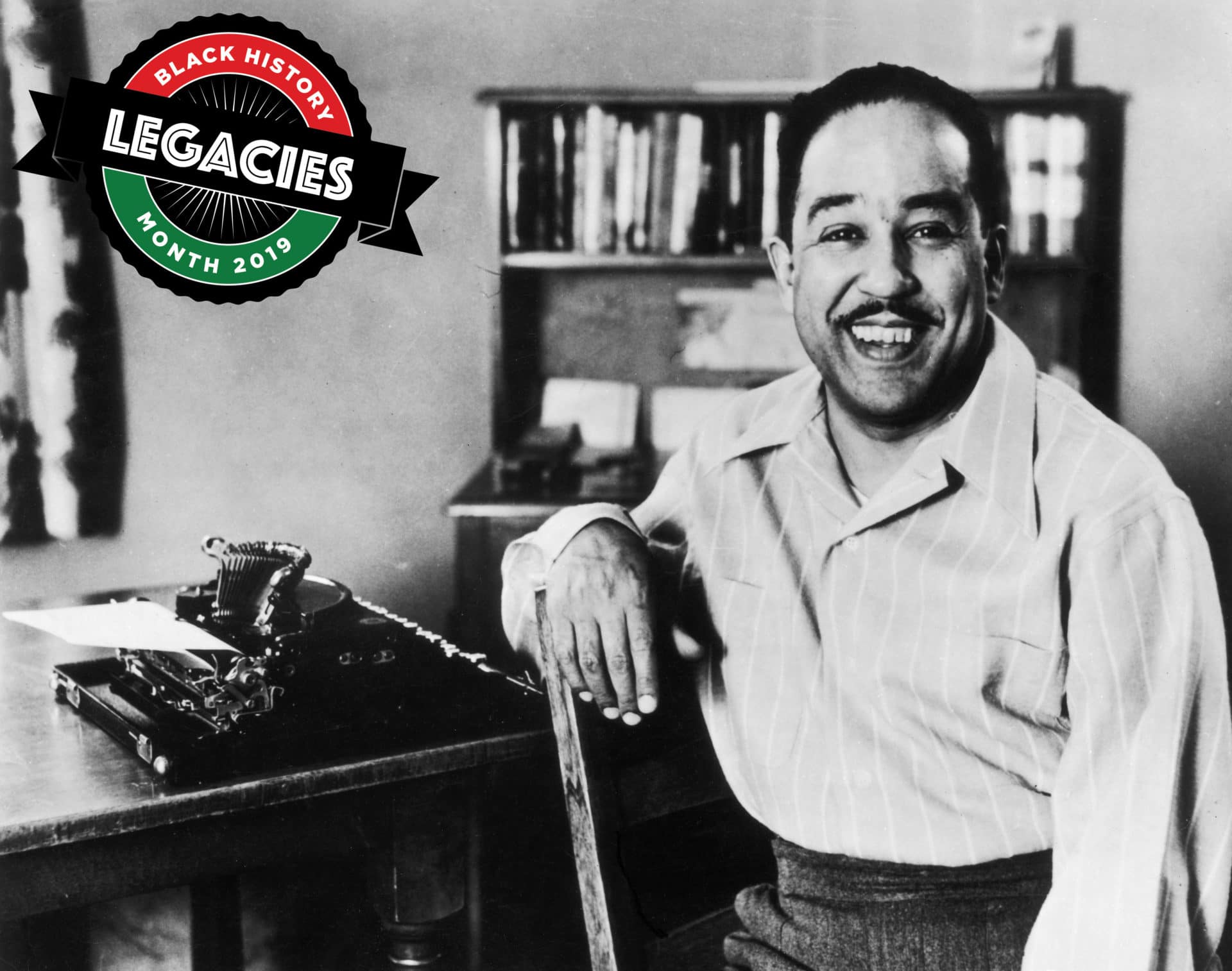

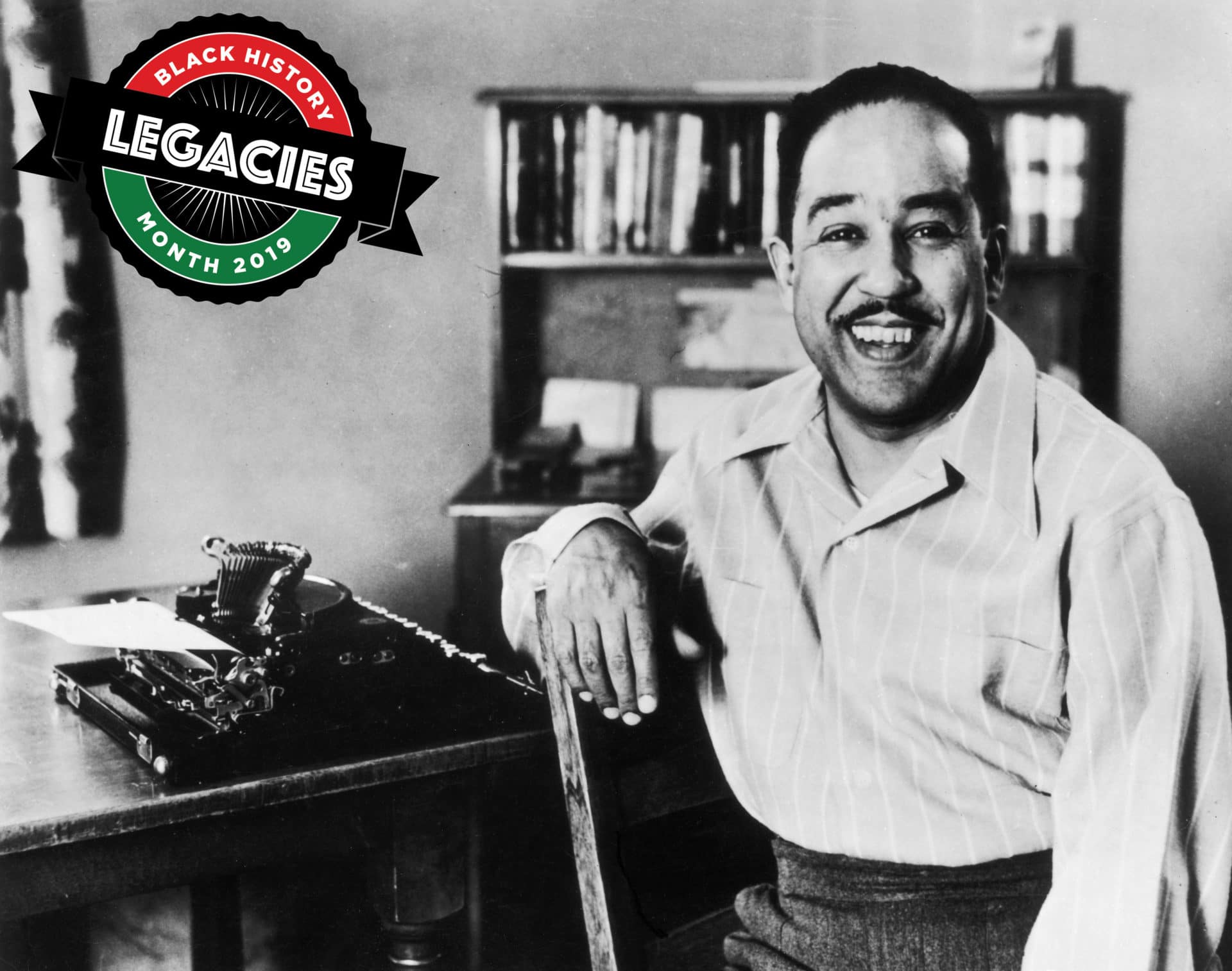

“Hold fast to dreams, for if dreams die, life is like a broken winged bird that cannot fly,” are just one of the few lines of prose created by Langston Hughes. Hughes is seen as the face of the Harlem Renaissance and with his deep history and his legacy that is celebrated every Black History Month, and his family is making sure his dream and memory are kept intact.

Harlem was a dream for African Americans in the 1930s and 1940s. There was something magical happening and it all seemed to be taking place in this one city of New York. As a little girl, I was raised with the soul of Harlem; I never quite understood why I was so drawn to a city I never been to, but the books I read told this story of a city that celebrated people that looked like me. It was almost as if Harlem was heaven; a place for African Americans to be themselves completely without prejudice and discomfort.

The African American experience isn’t complete without the history of one’s family. The stories, recipes, and even facial details are all examples of things that tie us to people who share our bloodline. For the majority of African Americans, it’s hard to find our beginning. When we were brought to this country there was no intricate record keeping of families and children were often torn from their mother’s arms. But for a small portion of us, some are lucky enough to find their beginning and people like Marjol Collet, safekeeping her family history was something she was destined to do.

“Langston Hughes is my second cousin. My great grandmother and Langston’s father are siblings. My mother had all these pieces, and so she called her brother and she said, ‘I think Aunt Jessie was right, Langston is our cousin.’ When she passed, they were given to me,” Collet tells ESSENCE.

Collet decided to do something differently. She realized that with one phone call, something sparked, instead of being a stationed museum, why not take the museum to the world? Collet started the

Langston Hughes Family Museum, a traveling museum which entails taking 175 pieces of original Hughes family artifacts. Collet travels to different historical events with Hughes’ family memorabilia on display to educate others about the Hughes family history. Collet answers questions pertaining to anything shown and is primarily for Hughes scholars who want to know more than just his works; this is about his life and the people that loved him.

Saving family artifacts wasn’t something that started with Collet, her mother safeguarded family keepsakes, and despite Collet’s pleas to help, her mother wouldn’t let them out of her sight.

“My mother use to carry this book around that contained memories, and I use to ask her all the time to let me take care of it, but she never let it out her sight. When she passed I started finding things and placing them together and preserving, it just started to grow!” she says.

But what’s Collet’s favorite memory of her cousin?

“When Langston came to town in Chicago, we went to visit him at the Conrad Hilton. He was being interviewed on TV, and it was a big deal! Mahalia Jackson was on the show with him. I was so star struck by her, that I didn’t even give Langston a second thought! To me, he was just my cousin. It was a moment I will never forget,” she recalls.

For most African Americans, finding our ancestral makeup is harder than finding a needle in a haystack. We were brought over with no records, changed identities, and broken families. Protecting Black History goes deeper than just remembering who sat in the front of the bus or the first to attend a PWI, its remembering and finding out who you are.

Whether you have a famous cousin or not, protect your black history and safeguard the memories and traditions that bring joy and security to your family. Black history goes beyond a book, it starts with you.