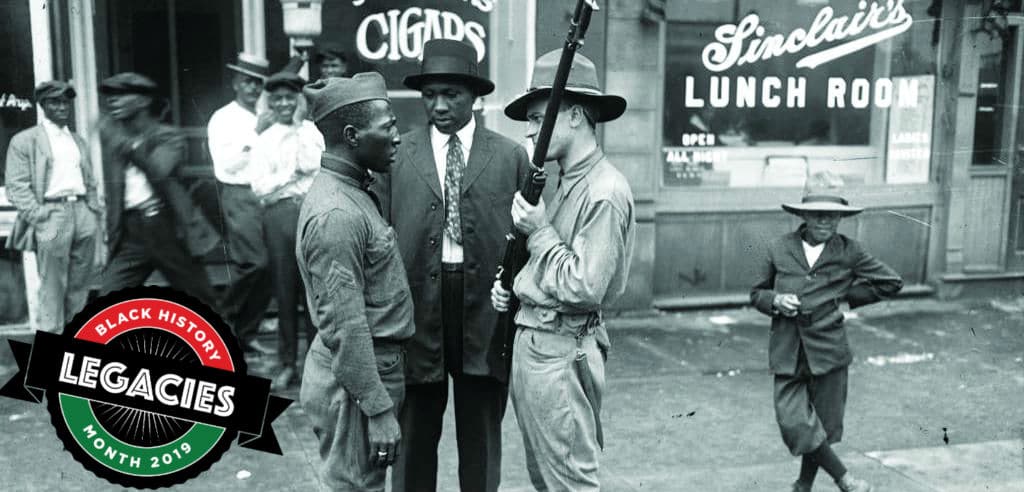

2019, like any date on the calendar, marks an anniversary of American violence. In this case, 2019 is the centenary of the cluster of organized violence and terror against Black people that would come to be known the “Red Summer”—so named by novelist, poet, activist and NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson. As U.S. involvement in the Great War drew to a close, Black veterans were still fighting “against the forces of hell” in America,

according to W.E.B. Du Bois—fighting to be deemed as fit to live, having returned from war, as they had been fit to die going into it.

NAACP membership increased, and Black workers fortified unions and formed new ones. The northward exodus of Black Americans, ongoing since the start of the war, intensified. They were moving to and searching for an opportunity, wherever they could find it or make it happen. “From the moment the emigrants set foot in the North and West, they were blamed for the troubles of the cities they fled to,” Isabel Wilkerson writes in her Pulitzer Prize-winning

The Warmth of Other Suns. Neither the government nor whites, operating largely as one, were comfortable with the idea of Black citizenship. White people took action. Blood was shed. People died. History has called these events “race riots.”

“Race riot” is a misnomer. When white people marched on Hard Scrabble in 1824, on Cincinnati in 1829, on Snow Town in 1831, on Cincinnati in 1836, on Cincinnati in 1841, on Philly in 1842, on Detroit in 1863, on New Orleans in 1866, on Memphis in 1866, on Phoenix in 1898, on Wilmington in 1898, on Atlanta in 1906, on Charleston in 1919, on Memphis in 1919, on Macon in 1919, on Bisbee in 1919, on Scranton in 1919, on Philly in 1919, on Longview in 1919, on Baltimore in 1919, on Washington, D.C., in 1919, on Norfolk in 1919, on New Orleans in 1919, on Darby in 1919, on Chicago in 1919, on Bloomington in 1919, on Syracuse in 1919, on Hattiesburg in 1919, on New York City in 1919, on Knoxville in 1919, on Omaha in 1919, on Elaine in 1919, on Ocoee in 1920, on Tulsa in 1921, on Perry in 1922, on Detroit in 1943 and on Charlottesville in 2017, it was no more a race riot than when 21-year-old Dylann Roof opened fire on the group of 12 gathered in prayer in Charleston on June 17, 2015.

“Race riot” is a distraction. We’ve made the term so matter-of-fact while the maelstrom of history moans all around, like a softball thrown into the eye of a hurricane. Use of the modifier “race” deliberately omits the matter of who and whom—who attacks whom, who lynches whom, who massacres whom, who bombs whom, who will not rest until breath cannot be sustained by whom in this country. “Riot” is no better, making premeditated murders more resemble crimes of passion, a category of abuses that America is inclined to forgive.

There was no reason to call these events other than what they are, except to suspend tragedy and foster disbelief. For, as poet Steve Light

points out, “a term was already in existence which could have been used for the aforementioned attacks and massacres: pogrom.” From Yiddish and Russian, a pogrom is “an organized, officially tolerated, attack on any community or group,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary, and originally applied to Russia’s organized massacres of Jewish people in the 19th century.

America’s frequent pogroms were not, just as its many individual lynchings were not, motivated by the need to defend white women’s mythical purity. It’s been over a century since journalist

Ida B. Wells dispelled the misbegotten idea that white people had been killing Black folks all that time solely to preserve their women from some perceived lecherous intent of Black men, risking limb and life to do so. White women’s chastity was at best an alibi for the roiling white resentment especially inflamed by the mere

prospect of Black economic progress. The Emancipation Proclamation was an affront, and Southern Reconstruction a debasement worse, in their minds, than the centuries of enslavement that preceded it. After the party of Lincoln rolled over and showed its belly in the Compromise of 1877, the white South vowed to make the Black South pay. The white South—and North and West and East—still vows it.

The Marrow of Tradition, published in 1901, expounds upon the real-life racial violence that erupted on Nov. 10, 1898, in Wilmington, North Carolina. Not a riot but a “coup d’état,” so says author Charles W. Chesnutt in his keen Southern novel, which Du Bois called “one of the best sociological studies of the Wilmington Riot which I have seen.” For the months leading into the nation’s 1898 midterm elections, various groups unofficially associated with the Democratic Party—including Wilmington’s “White Government Union,” whose constitution expressed its goal to “re-establish in North Carolina the SUPREMACY of the WHITE RACE”—had ramped up intimidation with lethal purpose. By early November, mobs of a thousand armed white men regularly patrolled Wilmington’s Black blocks, shooting at churches, homes and schools.

In Chesnutt’s novelization, the days leading up to what would be called a race riot saw Black residents “oiling up the old army muskets,” or simply spiriting away, “disappeared from the town between two suns.” Those who remained, in truth as in fiction, faced a mob of armed white men 2,000 strong. The precise number of Black dead remains for now (and forever) unknown. There were no white casualties. In 2006 a state-appointed panel called the 1898 Wilmington Race Riot Commission determined that the violence was not a riot but part of “a documented conspiracy” that “took place within the context of an ongoing statewide political campaign based on white supremacy.” In 2007 the North Carolina Democratic Party State Executive Committee

passed a resolution renouncing “the bloody massacre.” And yet still we call it, and so many of its kind, a riot.

If the story sounds familiar, it is because so many of these so-called riots begin and end this way, with Black people doing something that ought to be so ordinary—working, walking, writing, praying—and being met with white terror for their trouble. In Chicago the teenage Eugene Williams was swimming. Out of that history, and the present, blossoms Eve L. Ewing’s second poetry collection,

1919, forthcoming in June from Haymarket Books.

Race riots were not interracial struggles but, rather, were coordinated acts against the possibility of Black survival. 2019 is long past the time to call violence by its name, lest we continue to be haunted by a past not yet past.