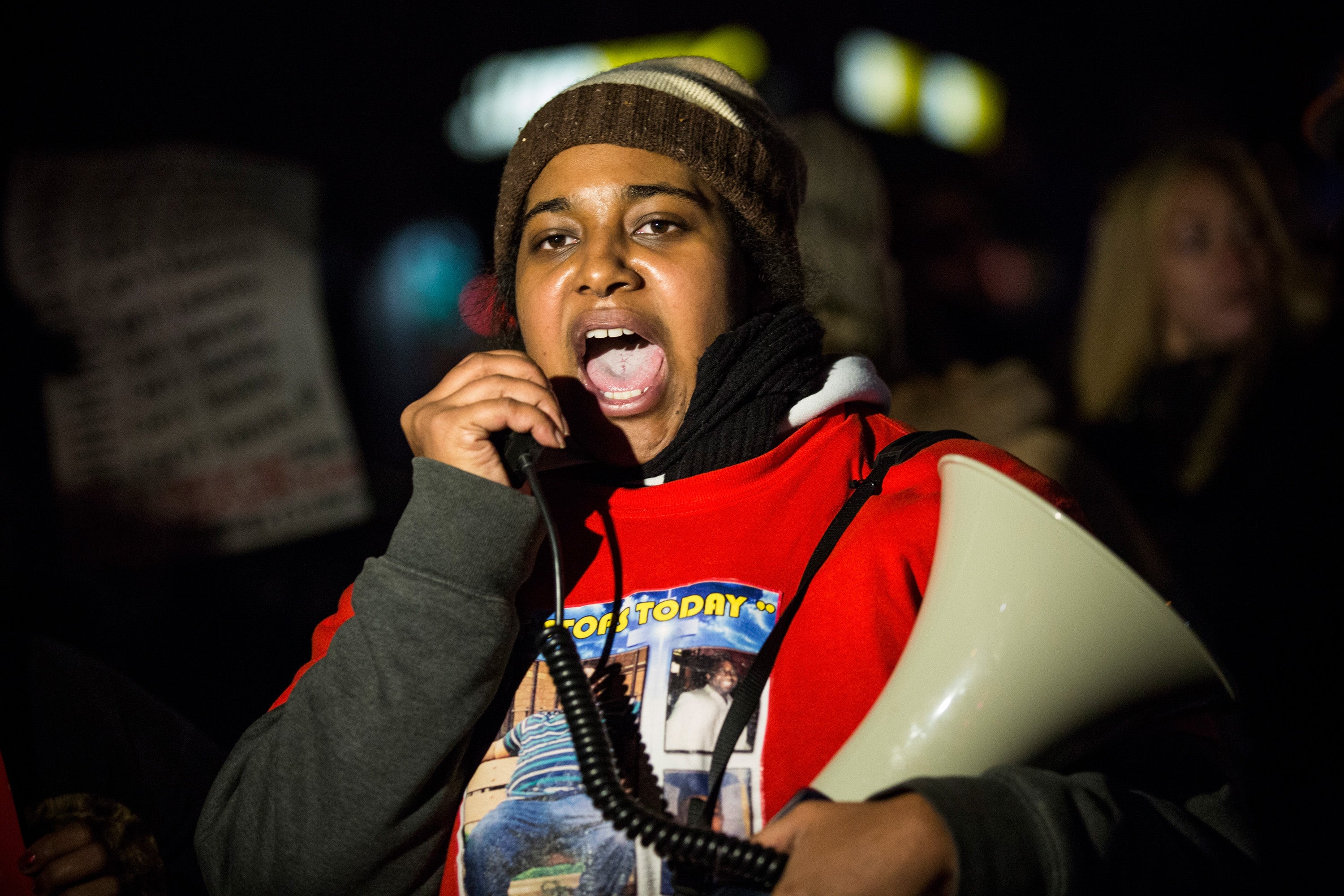

“I’m struggling right now with the stress and everything,” explained Erica Garner shortly before an asthma episode that caused her fatal heart attack in 2017 at the age of 27. “This thing, it beats you down. The system beats you down to where you can’t win.”

Her words illustrate the literal and metaphorical struggles endured by Black activists. There is no shortage of individuals, like Martin Luther King Jr. and Medgar Evers, who lost their lives in pursuit of racial equality. The Black community is all too familiar with death as a consequence of racism. Still, without considering the impact of institutional racism on the life spans of activists, we overlook a critical piece of the puzzle.

We’re more likely to die as a result of the environmental and social circumstances of institutional racism, as Garner did, than from bullets, like King. Systemic racism leaves Black Americans more susceptible to a range of illnesses and diseases—both of which limit our ability to eradicate injustice.

Long-term exposure to racism impacts the mind and body. Black Americans face a higher risk of heart disease, mental-health challenges and even death, and activists have an increased risk of health problems, too.

“Fighting for injustice—although a noble and courageous act—can, over time, drain our energy reserves. When this happens, it can lead to prolonged stress and can cause burnout or caregiver fatigue,” says Dr. Jacque Strait, a licensed psychologist in the Houston area, who specializes in counseling services for women of color and is founder of Fit for a Queen Wellness Consulting.

It’s not uncommon for activists to have depression, difficulty sleeping and other problems because of stress. To combat these experiences, it’s vital that those fighting injustices remain aware of how environment is affecting their health. Strait lists specific signs that oppression is getting you down.

“Signs that your mental health is being impacted by oppression include mood changes (depression and anxiety), difficulty trusting others who are outside of your social and family network, feelings of isolation or loneliness, changes in sleeping and appetite patterns, feelings of helplessness or hopelessness, anger, irritability, withdrawal from others (or a decrease in quality interactions), uncontrollable crying or numbness,” Strait explains.

The term “self-care” is a buzzword these days, but minding your health is a nonnegotiable aspect of fighting for social change. For Black activists, the most rebellious form of resistance is to take care of yourself.

And in the Black community, activities that promote physical health, like exercising, eating a healthy diet and seeking bias-free health care, must be incorporated into our images of self-care. This is especially true when we consider the damage that heart disease, diabetes and other preventable diseases are doing to our community.

We saw the importance of cancer screening from Stokely Carmichael’s untimely death at age 57 from prostate cancer, which affects Black men at a rate 50 percent higher than white men. with double the mortality rate. One cannot have a long lifetime of fighting injustice—or have the opportunity to see the changes brought about by that activism—if one dies prematurely. Consider how much larger an impact Fannie Lou Hamer could have had if she hasn’t died from complications of hypertension and breast cancer at age 59.

For Black Americans, self-care also means a commitment to regular checkups to offset a heightened risk for certain cancers and other life-threatening ailments. Though it’s far from easy, minding our health means taking a creative approach to limiting our exposure to stressors, even while surrounded by constant reminders of oppression.

Belief in a higher power, commitment to one cause instead of many and developing supportive social networks can all be helpful in your “stress-reduction tool kit.”

“Using your support structures can serve as a protection against feeling isolated. Having an understanding and accepting space to talk about your experiences will help buffer against feelings of loneliness,” Strait says.

We must also stay mindful of the stimuli that trigger negative emotional responses, like social media, news and even relationships, and know when to remove ourselves. It’s OK to avoid smaller battles to save your energy for the war.

Strait suggests thinking of these tactics as immunizations to protect you from burnout.

“Taking care of yourself—recharging your batteries—will give you the energy to continue in activism by decreasing the chance of burnout. It’s in your best interest, and your causes’ best interest, to engage in self-care.”

Don’t allow the world to change you or lead to emotional exhaustion while you’re fighting for the cause. Check in with yourself regularly to make sure you aren’t losing your compassion while fighting for change. It may sound counterintuitive, but it’s important that Black activists put their needs first.

“Neglecting your own self-care for the cause will ultimately lead to problems with your own physical and emotional health, which is not aligned with your cause. Be mindful of your unique needs through mindfulness, reflection and intentional self-care,” Strait concludes.