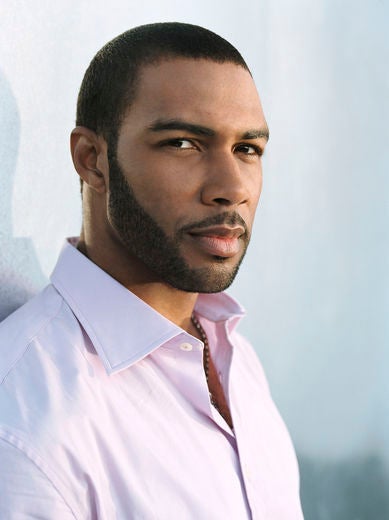

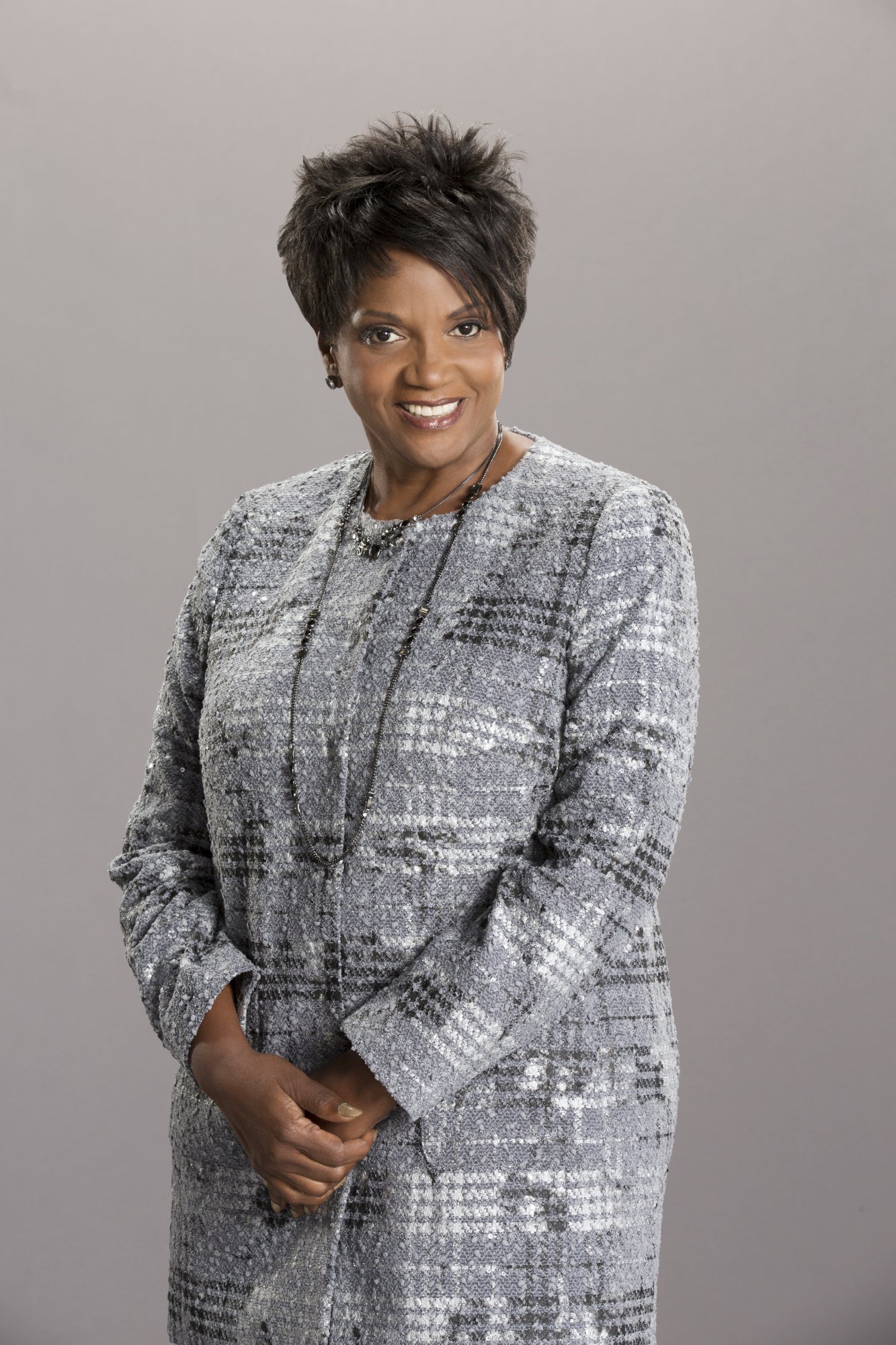

When D’Angelo finally returned with Black Messiah in December 2014, the long-awaited album anointed Kendra Foster as a funk-soul Mary Magdalene. Co-writer on eight of the album’s 12 tracks—including the Grammy-winning “Really Love”—Foster continued her coming out party as a background singer with D’Angelo & the Vanguard on The Second Coming Tour last year. And her mystique played its own part in D’s resurrection: she gave no interviews. Dig up the former P-Funk singer’s independent debut for clues (spring 2014’s Myriadmorphonicbiocorpomelodicrealityshapeshifter), and her silence seemed to say.

Kendra Foster, her new self-titled album, breaks the silence. Foster’s “overnight success” came through stints with bands like Smoke, Fish-n-Grits, Concept and Children of Production, plus paying dues touring as a Parliament-Funkadelic All-Star. (The Tallahassee native first met P-Funk founder George Clinton as a former Florida A&M jazz studies major.) Now, with Chaka Khan and ’70s soul-influenced singles of her own—see “Promise to Stay Here”—she leaves no doubt about who she is and what she’s bringing to the table.

How did you meet D’Angelo?

There were many near misses, but around 2008, George Clinton was having a birthday party in L.A. I was ready to leave and a bunch of people in the band were all on the party bus outside. George’s daughter comes on [the bus], and on her phone she had a picture of D’Angelo. I was like, “Put us in touch!”

So a few months later, I was on a layover and I got the nerve. “Hello, may I speak with D’Angelo…? This is Kendra Foster, the girl from P-Funk. The redhead one, not the white girl… [laughter] I’d always wanted to work with you.” He was just, “OK, yeah, cool. Send me a sample.” I sent him a sample of my writing. He had actually recognized me and was already trying to find me because he saw me perform on the Montreux Jazz Festival with P-Funk.

We could never connect until I moved [to Brooklyn] in 2009. We met up at the studio, and only then he played me some of the stuff that was soon to be on Black Messiah. And then some things were created fresh.

How were those sessions for you?

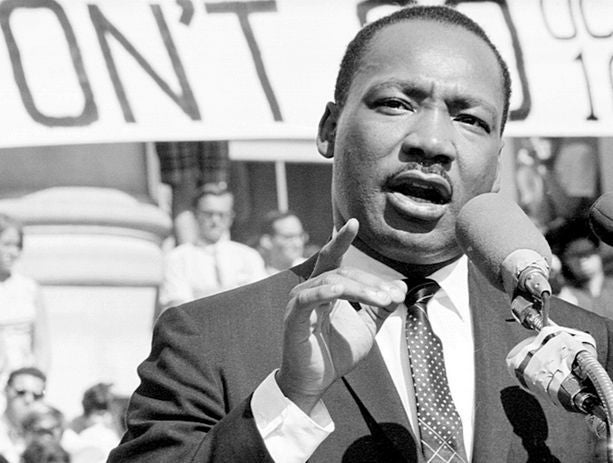

Well, it was amazing. At first it started off more submission-and-approval, with things like “Sugah Daddy,” “Ain’t That Easy,” “Really Love” and a couple of others, where I’d be filling in the blanks and I’d check back with him. But then there were times where we’d actually be able to just sit together in the studio, which was really awesome. I find him very kindred musically. And his notes were excellent. They were very intellectual; I felt intellectually challenged. “Hey, say something like what James Baldwin would say through Dorothy Parker’s voice” or something. And you’d be like, “Yeah!” [laughter] He really is brilliant musically. I didn’t have to change my voice to write with him. I really was able to be myself and speak out about issues, social injustice, the community and inhumanity at large.

Did he offer anything for your album?

He said I could have a little ditty, but that may have to come on the second album. There’s still more stuff to come from D’Angelo & the Vanguard; it’s in the works.

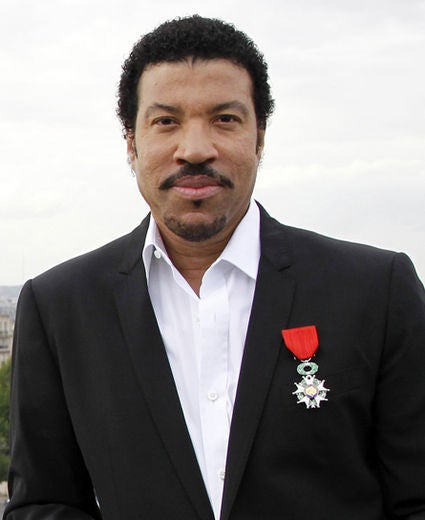

“Promise to Stay Here” recalls Rufus’s “Tell Me Something Good.” How do you find your own voice through allowing other people to influence you?

Belita Woods—she was with a group called Brainstorm, later played on Journey to the Light (amazing album) and with P-Funk—showed me my voice in a way, by being an older version [of me]. I don’t mind mimicking. Because I couldn’t find my voice until I realized that mimicking and just loving it so much you wanted to duplicate it gives you your own vocabulary to be your own author, with your own voice. The mimicking builds the vocabulary.