Today is the first day of December on the Bowery. The historic corridor running up Manhattan’s skirt is decked with balsam fir branches, weighted with tinsel, golden baubles, and pine cones. True winter is finally in the air- blaring like Mariah Carey out of every boutique and bar- in these East Village streets. The sun begins setting every afternoon around three, and today is particularly miserable. It’s cold, but not cold enough to freeze or fluff the steady, light rain falling out of a blue-black sky.

In all this dark, the brightest light on the block is emanating from the wide smile, the intensely expressive, almond-shaped, soup bowl-sized eyes of Rasheeda Purdie, the proud chef and owner of New York’s City’s newest, and most unique ramen shop, Ramen by Ra. Amidst a speech of characteristically hyper-focused, precise, pre-edited full sentences, the intense and passionate, deceptively small and slight young chef- holding a head of full-length dreads high- delivers her mission statement to a riveted audience, “I didn’t want to make ramen without y’all being able to see me in it.”

Rasheeda is addressing a cocktail party celebrating her first day of “business”- what’s known in the industry as a friends and family event- personal and professional acquaintances have shown up for a sneak peak of the soon to open micro restaurant. A small crowd is tasting Rasheeda’s Potlikker Ramen- derived from cooked collard greens and the resulting flavorful braising liquid- from coupe glasses, and sipping mugs of hot cider spiked with Japanese whiskey. We’re on the Northwest corner of Great Jones Street, in a five kiosk enclosed food lot called Bowery Market, directly across the street from a loft where Basquiat used to paint. The cocktail party has been assembled in honor of Rasheeda’s unusual five seat ramen counter and across it, an area the size of a galley kitchen in an improvised studio apartment, built into a crease in the market’s far corner, where the ramen will be made. Through it all, Rasheeda smiles, as this is her victory lap, the culmination of years of study, hustle, and unprecedented community support.

I first met Rasheeda in Harlem, in October. We met up at the acronymed ramen shop ROKC for oysters and noodles, where her passion for ramen was sparked in earnest and the staff still recognizes and welcomes her warmly. The neighborhood is where she began her journey, quite appropriately, at Melba’s. Melba’s is one of Harlem’s great soul food restaurants, named after its chef owner Melba Wilson, the niece of the late legend, Sylvia Woods. From there, her education at the side of Harlem royalty continued, with chefs JJ Johnson at The Cecil, and Marcus Samuelsson at Red Rooster (where she introduced her first ramen bowl in 2018).

The pandemic gave Rasheeda the time and reflection to turn her passion for ramen into her life. She taught herself the basics at home, began developing her own vision of the cuisine, and Ramen by Ra was born at a series of events and pop-ups post-pandemic. The radical shift was par for the course for Rasheeda. The FIT grad once traded in a lucrative, near decade long career in fashion, at the dearly departed Henri Bendel, for culinary school. The secondary pivot from the safety of an institution like The Cecil or Red Rooster, from the run and gun mercurial freedom of the freelance pop up world, to the heavy risk and immense labor of running her own tiny, independent shop, is just another leap she’s made routine.

Rasheeda represents a radical shift in ramen- in what ramen is and who gets to make it- and a return to a moment not so far removed from today. There have been several movements, generations of ramen in New York City over the course of the dish’s 50 odd years here (The first Cup O’ Noodles allegedly landed in America in 1973). Ramen by Ra is a charming throwback to the dawn of its postmodern era, following the chef and Momofuku emperor David Chang’s bomb drop with Noodle Bar. In his wake, dozens of domestic chefs came forward with their takes on ramen, using it as a vehicle for ideas and translating American dishes, using ramen’s elements to reassemble our classics in abstract. Suddenly a bowl of ramen could feature lobes of foie gras, or fried chicken, or black truffles, or smoked salmon, or lobster tails, or matzo balls. Rasheeda has taken this idea and cast it in the tradition of Black American cuisine.

Today, in an industry that continues to make strides but is still largely and tyrannically male, ramen stands out as a “Boy’s Club” inside of a Boy’s Club. Walk into any of the city’s proliferate noodle factories and you will see mirror profiles of predominantly scrawny men in button down dishwasher shirts ladling steaming broth and nestling jammy eggs into ramen bowls. Rasheeda acknowledges this and embraces her otherness in the medium, saying, “I want there to be an understanding of the feminine side of ramen, because it’s so masculine. It might be a handful of women, but we’re out here.”

Perhaps, finally, the time is right in ramen for a narrative like Rasheeda’s, as evidenced by the chef and her food’s instant, viral popularity. She is a Southern Black woman from Prince George’s County breaking the unofficial ramen barriers of gender and race, and she’s disruptive beyond those dull checked boxes of market demographic. As Rasheeda put it, “The ramen that I create is me being able to infuse the culture, so that my world and my community will be open to it. My goal is to create conversation. We’re in 2023 and the face of food is endless. I can’t help but to be inspired by something I personally love, and why shouldn’t I be?”

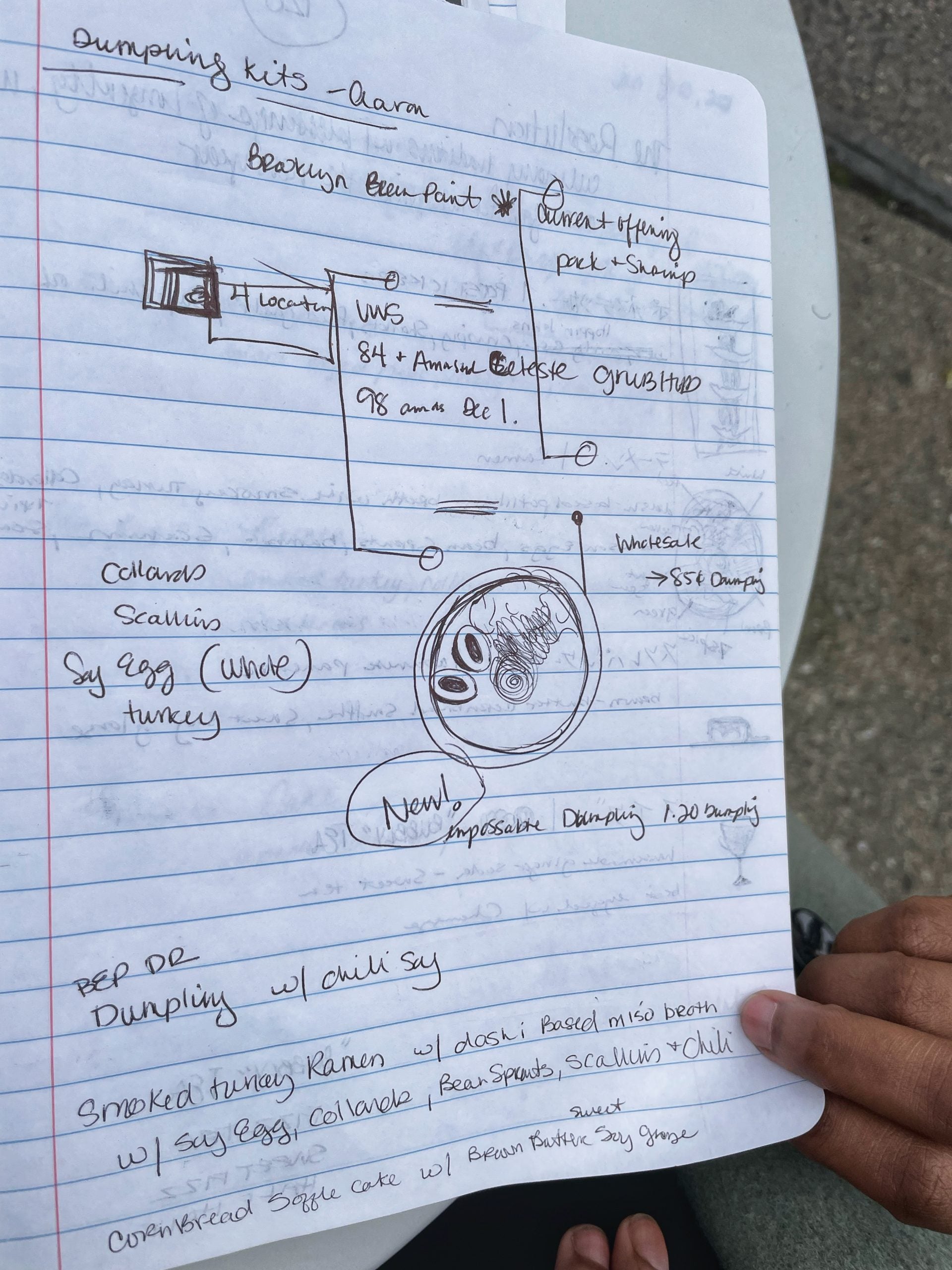

Opening a restaurant can’t “just” be the work of inspiration, playing with food as you research and develop your menu. For the most part it is grueling, tedious work, and it’s work I watched Rasheeda do through the fall. Her two largest obstacles were budget, working with a relatively scant $38,000 and change miraculously sourced from Kickstarter, along with her own savings, on a tight schedule, and the limitations of her space itself, that tiny 85 square foot sliver of Bowery Market where she’ll have to be able to meet the demands of a fully equipped and full sized ramen kitchen. This requires meticulous planning and constant, dynamic invention. Rasheeda showed me stacks of her marble notebooks, filled front to back with recipes, schedules, and diagrams. She’s coming into this eyes open, knowing exactly how many pounds of protein she needs to produce how many quarts of stock that takes X hours and has to be made twice a day over the course of a week to serve X number of guests. But she still needed to do the legwork.

We traveled to Borough Park in South Brooklyn to shop for lowboys, ones that could slot in underbar and maximize every square inch of cold space she’d need. We traveled to Greenpoint to taste and discuss tea which will be paired with her seasonal ramen offerings. We traveled to Chinatown to price out chicken feet at local butchers, in search of a vendor. As we walked down Mott, past windows gleaming with the burnished skins of garrotted barbecued ducks, Rasheeda illustrated why this work is so important to the success of a business with the tightest possible margins. At Ramen by Ra, she plans on offering a stock made without pork- chicken only- built primarily with feet and wings, high collagen value buys when you’re looking to build a rich and flavorful broth in a small space. The difference of a few cents can have a dramatic effect on her bottom line, and I was with Rasheeda when she discovered chicken feet at one butcher on Mott was $3 per pound more expensive than a butcher immediately next door.

Rasheeda had to convert her kitchen from a casual omakase to a ramen kitchen. This required reimagining the space, both functionally and cosmetically, work she did with the Land & Shore Creative Design-Build firm (or LSC) in Brooklyn. The snaking, cramped Bowery Market itself is reminiscent of Tokyo, an impossibly dense city in which sushi counters, yakitoris, and ramen shops are built into every subway station, side alley basement and freestanding food cart. Ramen by Ra leans into this with an edifice of burnt pine slats, produced via a technique known as shou sugi ban, which changes the molecular structure of the wood by flaming it with a roofing torch, making it more resistant to moisture, done in-house at LSC’s Brooklyn workshop. The result is a stall that looks plucked from Tampopo and planted on the Bowery.

Having spent so much time with Rasheeda as she struggled to build out her restaurant, it was a pleasure to finally spend some downtime with her, watching her enjoy the fruit of her labor, and to finally taste her food. It was fortunate, both for me and this piece, that my first taste of her Potlikker ramen was a revelation. It’s a dish only someone from Rasheeda’s background could’ve conceived, or at least executed in a way that both feels, and most importantly tastes lived in. Rasheeda says, “My first ever ingredients that I got my hands onto were collard greens. The nature of how you go about cooking collard greens is similar to how you make broth. My grandmother was a chef, and everytime I make it, it takes me back to being the girl at her table shucking greens. That was my duty.” As an adult chef, Rasheeda realized her grandmother had incepted her with a bowl that perfectly sums up her experience.

As you sip the potlikker, redolent with the smoke and fat of turkey neck and wings, and you chew the dab of collards- standing in for a broth-soaked strip of nori- and the pile of noodles, you understand the importance of fearless experimentation, of chefs moving outside their comfort zones. It’s what separates a dish like this from millions of ill-conceived gimmicky fusion plates: It reveals the commonality in a pot of greens and a milky tonkotsu, that a great potlikker and a great pork bone broth both require experience, thought, patience, and above all other things, love. It made me think of a poignant answer Rasheeda delivered when we first met: “So much stuff has been erased over time as it relates to African American culture, African American history. I even had to look at it in the beginning and say, ‘How do I not lose myself as a Black chef and a woman expressing myself through another cuisine? Early on I told myself, do what you can to infuse yourself into every bowl so that you’re not on mute. I want someone to look at my food and say, ‘Why are collard greens in here? Why does she have watermelon in here? Why does she have pickled shrimp with cucumber in here?’And understand it’s because I’m putting myself in this bowl.”