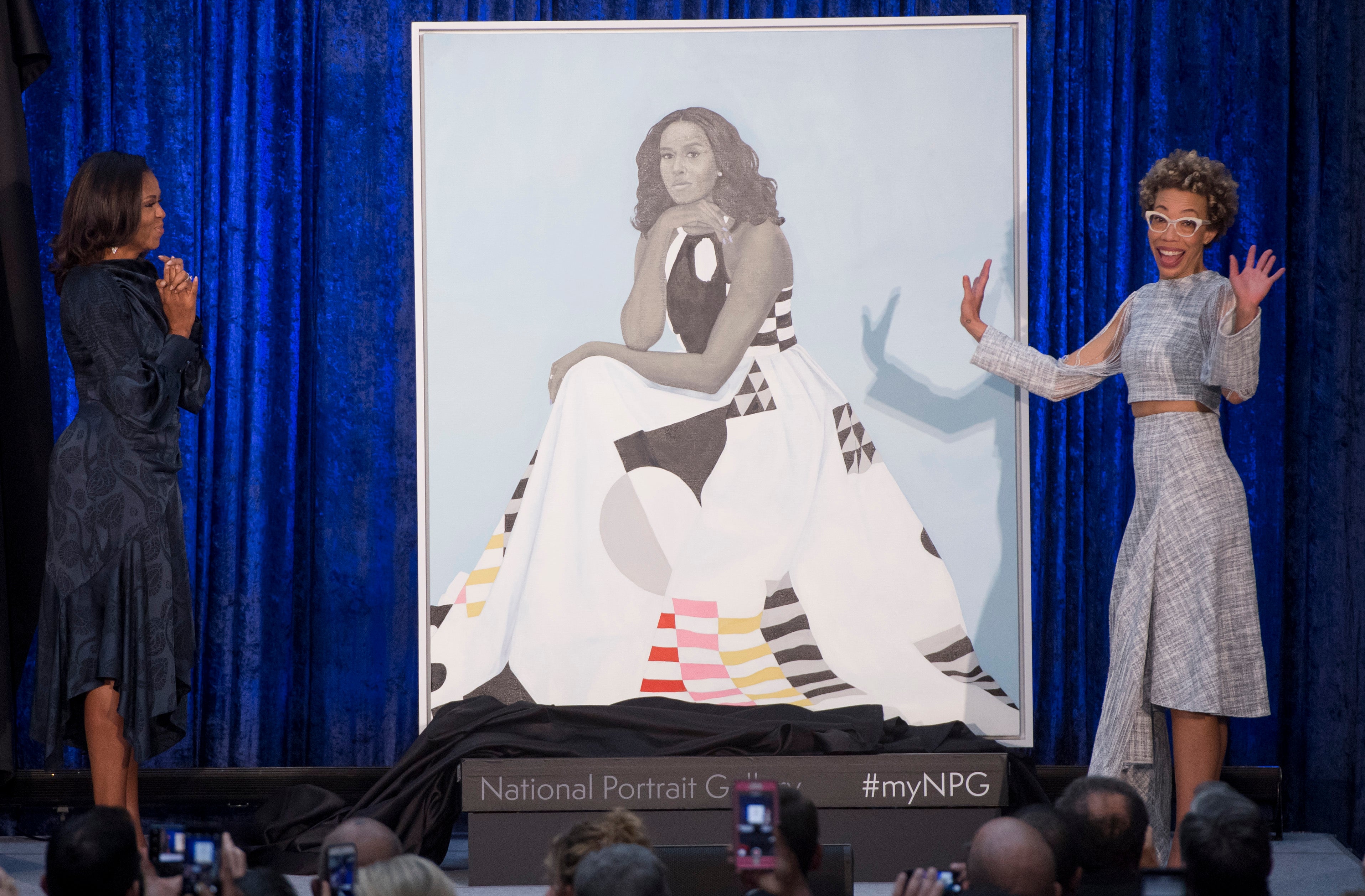

There are Black contemporary artists whose reputation reaches even those of us who haven’t hit up a museum in quite a while. The late Jean-Michel Basquiat inspired the 1996 biopic Basquiat, and his T-shirts are now sold in Uniqlos worldwide. Kehinde Wiley’s vibrant naturalistic art loomed large on Empire. Most of us know their work, and thanks to a recent commission by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, we’ve got another name to add: Amy Sherald (inset). Known for her signature gray-scale portraits of African-Americans, the Baltimore-based painter saw her profile soar with the February unveiling of her rendering of Michelle Obama (above).

The portrait that turned all of social media into amateur art critics overnight—our forever First Lady seated against a sky blue background and wearing a flowing mostly black-and-white gown by designer Michelle Smith of the label Milly—had a polarizing effect. Viewing Sherald’s oversize artwork in person does it the most justice. Pops of color in the quilt pattern come alive; Sherald’s distinctive use of a monochrome skin tone enlivens the azure backdrop. From 20 potential artists, some of whom were interviewed in the Oval Office for the chance to paint official portraits for posterity, Michelle Obama chose Sherald, and all those discerning eyes were pleasantly surprised when they Googled her other pieces after the unveiling.

“What else do you do after this?” she asks. “It’s part of a legacy; that’s the crazy part. The ancestors are all standing up clapping. I feel the history of what my grandparents have gone through, what my mother has gone through, and all those things kind of come to a head when something like this happens.”

Amy Sherald grew up in Columbus, Georgia, graduating from Clark Atlanta University and later traveling to Panama under the international artist-in-residence program of Spelman College. (“I was at all-White schools from kindergarten to twelfth grade, so I wanted to feel what it was like just to be me and not, like, Black Amy,” she recalls.) Though she also studied art in Norway and has curated exhibitions in Peru, her career hit significant bumps along the way. Diagnosed with congestive heart failure at 30 while training for a triathlon, she underwent a transplant nine years later. She also walked away from art for four years to care for ailing family members, and suffered major heartbreak, losing her father (to Parkinson’s in 2000) and her brother (to lung cancer in 2012).

Coming back to her craft, Sherald really found her voice, discovering a personalized style in the realism of everyday African-American subjects. “There are a million other paintings of people who aren’t brown—they’re just lying in the grass or on a swing,” she says. “I think that’s why it’s so relatable to all kinds of different people. I wanted to be in museums. I don’t do things to be small.”