Art takes up space. Where that space is and who is allowed inside of it is rarely determined by Black artists. Antwaun Sargeant is provoking audiences to think about what is absent from many of the gallery walls, museum catalogs, public sidewalks, and library shelves where legacies are carved in his debut exhibition at Gagosian.

“I think we have an obligation to not only think about this moment, but also think about the future and also think about the past and how artists have occupied space,” the director and curator told ESSENCE. “I think it is a moment of us sort of recalibrating and reconsidering Black creativity.”

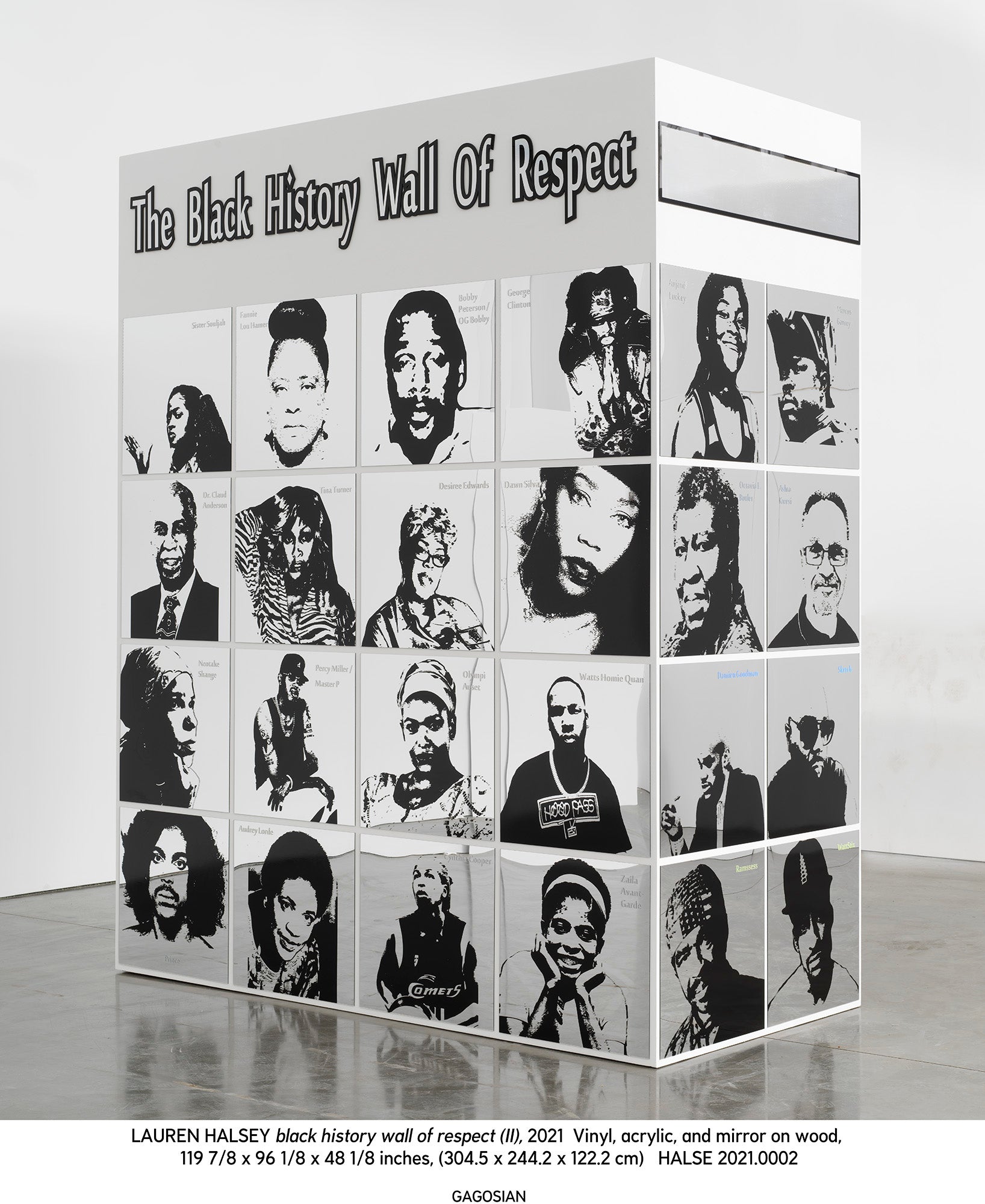

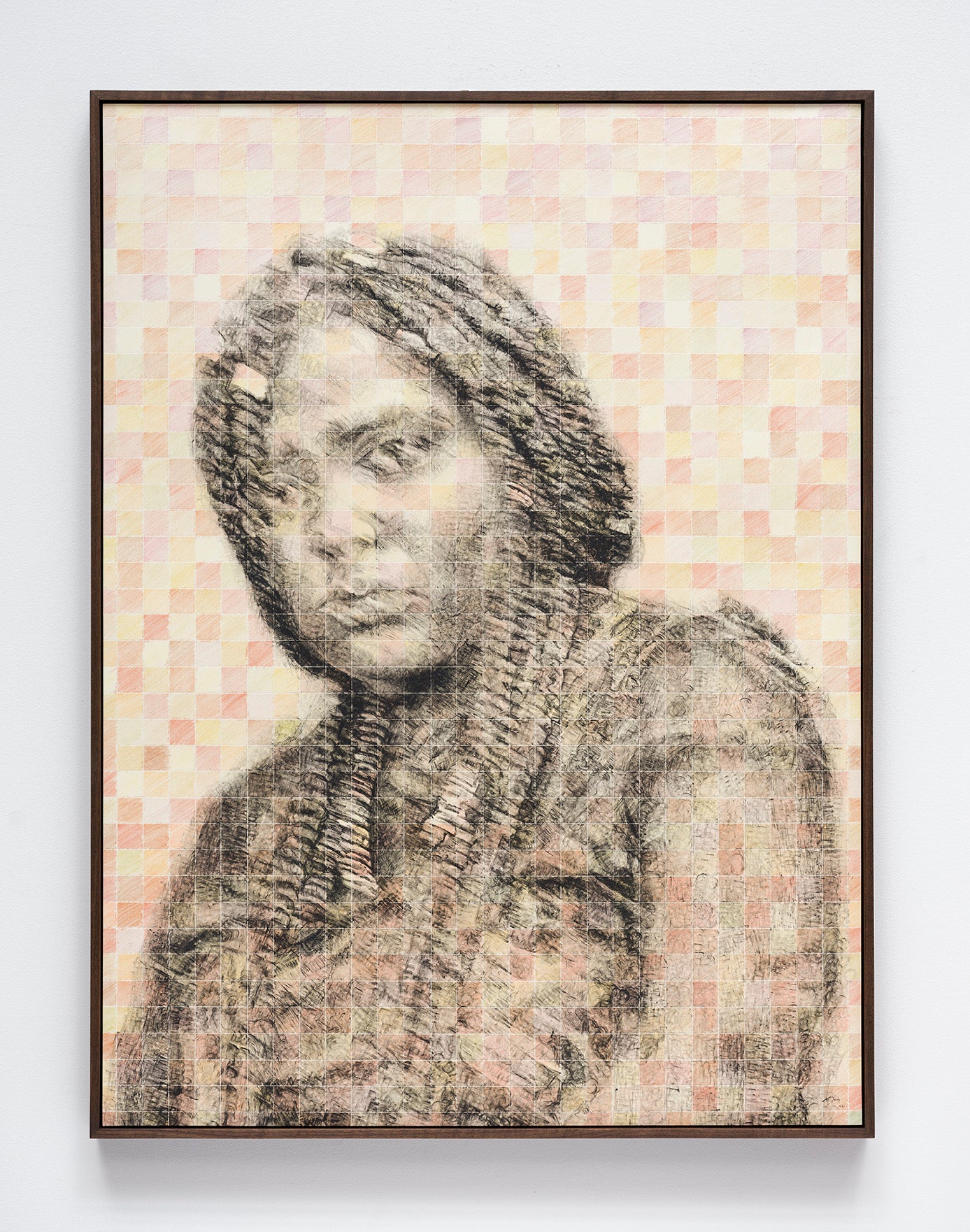

The multi-media exhibition, titled Social Works, examines Black social practice. It features paintings, sculptures, photographs, and installations by David Adjaye, Theaster Gates, Linda Goode Bryant, Lauren Halsey, Rick Lowe, Carrie Mae Weems, Titus Kaphar, and a select assembly of previous NXTHVN Studio Fellows.

“I sort of came upon this idea that it would be really great to do an exhibition like this, that sort of considers space and considers Black artists’ role in space as it relates to not only a museum or gallery but also to community,” Sargent explained. “This is a really great opportunity to sort of think about how artists have worked in the past to use space as a tool of empowerment but also how they’re doing that in the present to sort of try to discern what a future would look like.”

A renowned art critic who recently joined the gallery, Sargent has centered Black art in publications and books including The New York Times, W, Vice, Fader and The New Yorker The New Vanguard and Derrick Adams: Buoyant. “I’ve sort of devoted my adult life to better understanding Black artistic production and I’ve done that through not only writing about artists in essays but also making books about artists and also making exhibitions,” he said. “I think that in joining the gallery, I’m looking to continue that work to have a different sort of engagement with artists.”

That first expansion will be writing, which Sargent said he plans to use to build upon the conversation of the exhibition’s themes.\

Some of the pieces Sargent selected for Social Works honors marginalized artists in other genres. Theaster Gates’ installation is a tribute to “DJ Frankie Knuckles, a house music fixture who had commanded beats long before the onset of the EDM craze.

“The installation consists of 5,000 of Frankie Knuckles, personal records. These are the records he played in the club in the eighties and nineties,” said Sargent. “Music has played such an important central role to the way that Black people think about space, the way that Black people transcend space. Right? You think about the space of the dance floor.”

The installation was designed in partnership with the Rebuild Foundation, a Chicago-based nonprofit organization Gates founded which “focuses on art, cultural development, and neighborhood transformation.” Philanthropic initiatives are one lane where Black artists have carved out their own spaces.

“I think that is an important sort of aspect of the show,” Sargent said. “It’s not only just about, sort of, physical space, but it’s also about psychological space. It’s also about conceptual space.”

The exhibition will live beyond the walls of Gagosian’s facilities by claiming virtual space as well. Frankie Knuckles’ own personal archive will be digitized in the gallery. “It’s about preserving Frankie’s legacy,” Sargent said. “But it’s also about preserving the ways in which music has been a liberatory space for Black folk. So you have a work that generates space through that archival process.”

The effort is reminiscent of recent efforts to draw connections to modern creative spaces from previous virtual communities like Myspace and AOL Black Voices. “That’s where our history lives. Right? And so it’s a way to sort of preserve, Black history. And sort of think of history as something that needs a space, that needs to be maintained, that needs to be kept, that needs to be grown.”

Many of the artists featured began their career outside of the swank Chelsea addresses and behemoth institutions that declare an artist universally “important.”

Bryant’s Just Above Midtown Gallery (a favorite of Stevie Wonder’s) held space for “the artistic production of Black artists,” when it opened in 1974. But sadly, its innovative shows did not receive as much attention and acclaim as those embraced by the mainstream establishment. “That space was one space for that to happen, but I don’t think that was largely embraced by the wider art community,” said Sargent. Bryant focused on the impacts of the lapse in the art history world rather than the biases that created them. “It’s not even necessarily about the reasons it’s the fact that it didn’t happen and it has left a large space that has allowed for the contribution of all of our artists, like Linda, not to be properly registered in a sort of art historical context and not to be properly registered, in the way that we think about art and the possibility of art.”

The vacancy sparked powerful statements. “That absence has allowed for Black artists to consider those spaces,” said Sargent. He cited Carrie Mae Weems 2006 photo series “Roaming,” where the artist places herself in the void.

“She’s literally in these images, these black and white images, she’s literally juxtaposing herself, into institutions,” he said. “I think in that juxtaposition, you start to sort of wonder about the absence, who’s allowed in, who’s not, who’s not been allowed in.”

Those visiting the exhibition will be inspired to contemplate “What role does the Black, female figure play in art history.” They will also consider “what audiences these institutions speak to,” and “which audiences they don’t speak to.”

Another idea present in addition to “what does it mean to sort of take space,” is the question: “if you took that space, what are you going to do with that space?” The latter is something that those being recruited by institutions looking to correct their past misjudgements are forced to consider with every barrage of Twitter thumbs.

“That’s all embedded,” said Sargent.

Other subjects in the show explore the connection between art and gentrification, the Tulsa massacre, afrofuturism, and fantasy.

One of the boldest themes is the concept of parasitism, something many insitutions have been accused of in what some see is their haste to receive credits for superficial attempts at being anti-racist. Sargent places the ownership on “museums to ensure that this is not just a moment,” and to guarantee that when “the tragedy fades there’s still commitments to the issues and the concerns of Black artists.”

“This didn’t happen in 11 months, right? The way that these artists work hasn’t happened in 11 months,” he continued. “These problems that these institutions have around sort of representation and value and authority and, all of those things that sort of make up who gets seen and who doesn’t get seen in those institutions. That’s been going on for a very long time and I think that we are going to need more, we’re going to need just the same amount of time to sort of really unpack and really sort of transform our institutions.”

Social Works is now open at Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street New York, New York.