It was as if fliers had been posted all across campus, giving us just enough time to be prepared and creating a buzz that only comes during probate season. Weeks of secrecy and speculation would finally be over. Close friends and family were there with balloons and gifts. “Old heads” came back to make sure the yard would be in good hands. There were rumors of who made line, but it was obvious that everyone was there to see her.

The campus queen; everyone’s favorite.

She’d been laying low for a while — we hadn’t seen much of her lately. Constantly hard at work, it was her time to shine. And when she was “reintroduced” to campus, she gave us a show that reminded us of exactly why we love her so much and that she loves us, too.

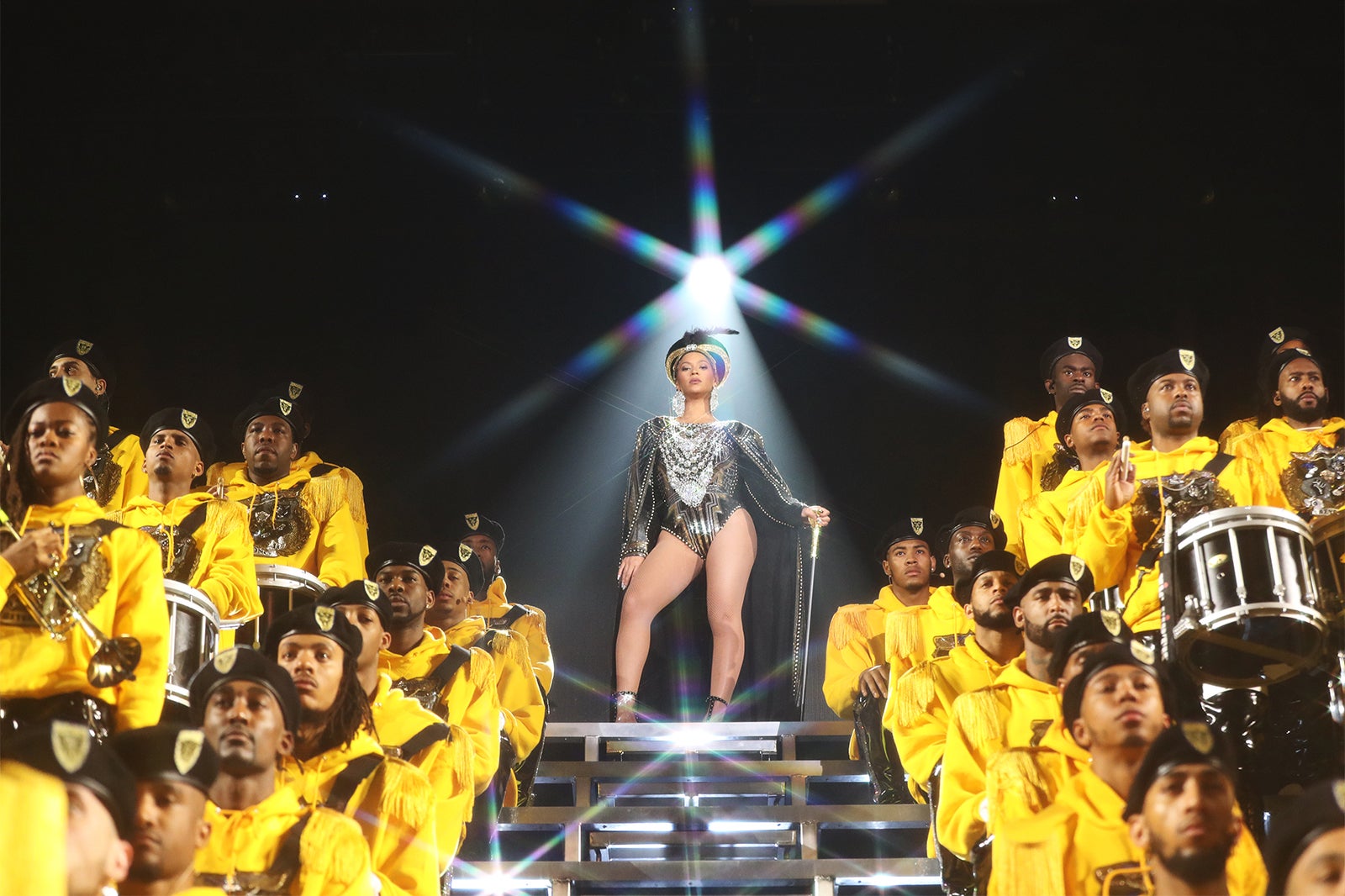

We didn’t know what Beyoncé would do at Coachella, but we knew that it would be epic. Would she perform new music in advance of the upcoming tour? The first Black woman to headline the music festival, we exhausted ourselves with the possibilities of how she would slay. Whatever she did, the consensus was that it would be nothing short of amazing. We missed her and we were ready — or so we thought. Beyoncé’s Coachella performance, appropriately dubbed “Beychella,” was nothing we could have expected. As only she could, she topped herself and took to the world’s stage, giving one of the most iconic performances in history seasoned and deep fried in Blackness.

She could have taken us anywhere. And she chose to take us to school.

A favorite red cup conversation among HBCU and Black Greek family alike has always been where Beyoncé would go and what she would pledge. Would she have attended a Black ivy or state school? Would she stroll across campus in pink and green, or post up with the Devastating Divas? While those discussions always contain a few playful jabs and end in laughs, Beychella showed us that it was irrelevant — Beyoncé made it clear that the entirety of the Black College experience is what grounds her. Being rooted in the Alabama and Louisiana identities that make her a “Texas Bama,” Beyoncé was reared in an environment that took pride in being Black. Growing up in a city with two HBCUs, she was further immersed in a community that intentionally celebrates Black artistry and reproduces Black excellence.

While skewed research reports and current news cycles work to question the relevance and vitality of HBCUs, Beyoncé’s performance was an ode to the institutions that have consistently shown her love. Whether in our strolls, probate routines, line names or halftime performances, Black colleges constantly lift the artistry of Beyoncé.

On Saturday, she returned the favor in a major way.

I sat in amazement at how she was able to articulate my decision to attend an HBCU, the entire college experience and every Homecoming as an alum in less than two hours. It reminded me of those days as a little girl, when my mother would get me out of school early for Winston-Salem State’s Homecoming pep rally. Growing up on the campus of her alma mater and watching her light up with her old classmates and friends made me yearn for that experience. Beychella reminded me of every A Different World episode and scenes from School Daze that I’d memorized, counting down the days until I’d be just like them. Even the “Bugaboo” probate took me back to that day in high school when I toured the campus of Tennessee State University and knew it was the only school for me. Beyoncé, in her Beta Delta Kappa sweatshirt, brought back all the emotions of seeing AKAs in their paraphernalia and working up the courage to express my interest to the right one at the right time. Watching the band perform, I couldn’t help but remember all the nights I heard them preparing for Homecoming. And when Destiny’s Child reunited and Bey danced with Solange, I teared up thinking about how much I look forward to that one weekend every year when I can forget about the real world, link up with my girls and be 20 again.

This is our real life; it is who we are. And Beyoncé put it on an international stage for the entire world to see.

For two hours, we were able to escape the harsh realities of our current racial and political climate and bask in the best of who we are. That has always been the gift HBCUs provide: safe space in a hostile world to be nurtured, challenged and educated. The ability of Beyoncé to replicate that sanctuary on a Coachella stage proves that she has not only benefited from it, but also recognizes its necessity.

But the Black college doesn’t just belong to its students and alumni. Black College culture is communal. It is shared with the groundskeeper who keeps our beloved “yards” lush with the welcoming green, representative of the famous HBCU space of gathering. It is shared with the cafeteria worker, who made sure students still ate when they were broke with no meal plan points. With the local business owner who made all the shirts and jackets; the people who attend plays and productions on campus. Our experience is shared with the members of our community who never enrolled in a class but make Homecoming the unofficial family reunion weekend. Through Beychella, Beyoncé paid homage to the culture that didn’t just start loving her when she became an international icon, but loved her when she was a little girl dancing along with the band at Texas Southern games and mimicking the moves of the Prairie View A&M Black Foxes.

Following Beychella, Tina Lawson took to Instagram to confess she was concerned that Beyoncé’s performance would be confusing to the predominately White Coachella audience. Mama Tina revealed that her daughter quelled her concerns, saying, “I have worked very hard to get to the point where I have a true voice and at this point in my life and my career I have a responsibility to do what’s best for the world and not what is most popular.” While we love all things Beychella, this performance was a major risk. Beyoncé is not far removed from the fallout police unions had over the “Formation” video and some White folk are still salty about her 2017 Super Bowl performance tribute to the Black Panther Party. A performance from the world’s biggest superstar featuring the Negro National Anthem, at a moment when controversies about the flag and national anthem are still at fever pitch, signals a woman who is both comfortable in her skin and aware of her global responsibility.

When Beyoncé tells her mother that she has worked hard to get to this moment where her “true voice” is all we hear, we know what she means.

While she has always been Black, her early career required a careful navigation of her Blackness to attain the level of superstardom she rightly deserves. We couldn’t have gotten Beychella 10 years ago. But she has worked hard to be able to captivate and maintain the world’s attention. And when she has it, in every way she can, she reminds them that Black Lives Matter. She made it clear that you cannot love her and lack a deep, profound respect for all that she is.

And this is why choosing the HBCU experience as the vehicle through which she delivered Beychella is so powerful. Those of us who chose to be educated in historically Black institutions were steeped in an unapologetic Blackness mirrored by that performance. Even the elements of Beta Delta Kappa crest (Queen Nertiti, the Black Panther, Black Power fist, Black bumblebee, cross, Eye of Horus and wings of Ma’at) reflect the ways the education we receive in and outside the classroom reinforce the blessing in being Black. Though our schools are not without their problems, we are placed in incubators that affirm we can be and do anything. Black excellence is not optional. At historically Black colleges and universities, it remains the standard. The power of Beychella reminds us that there are no parts of Black excellence that are not rooted in Black education and cultural production. And Beychella reinforced that we have never needed white spaces to validate us.

We have our own anthems, schools, organizations, rhythm and perspective that will always be more than enough.

Perhaps, what is most beautiful about Beychella is that Beyoncé believed it was the right thing to do. In a way, it was as if there were two performances happening at the same time that night. In one, she performed for her people — enabling us to remember and relive youthful, happier times. Her performance for us was a love letter that we will not soon forget. And in the other show, in her performance for them, she presented Black culture not for the world’s consumption but for its salvation. She lifted Black spirituality, artistry, education and activism to boldly proclaim that when the world recognizes the endless possibilities within Black culture and the humanity of the people who provide it, then — and only then — can we all be free.

Beyoncé didn’t have to give us Beychella. But she did. And all of us are better for it.