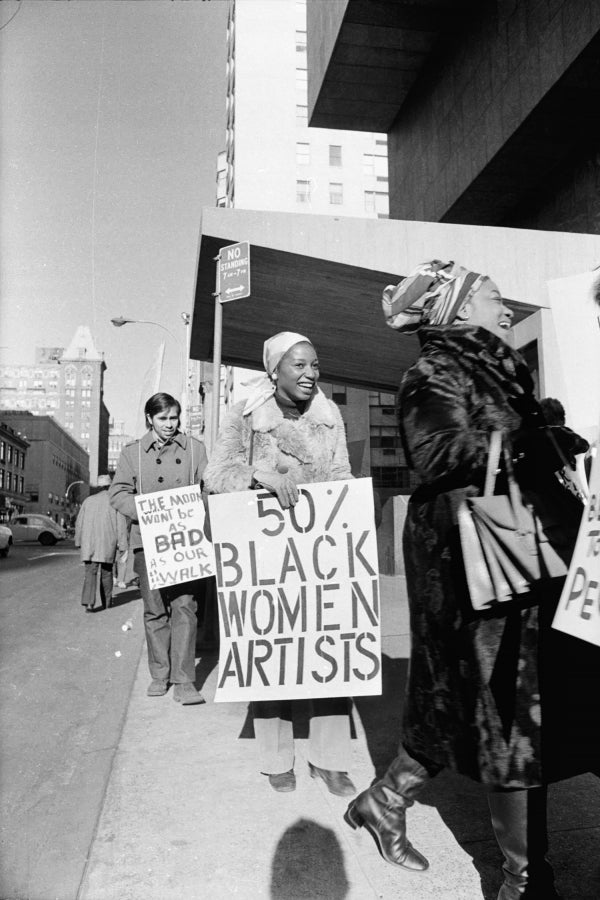

For years, the work of Black women has been overlooked and ignored.

Since the beginning of time, Black women have been the backbone of our country’s political and cultural movements. But our contributions have often been reduced to merely a footnote in history. The Brooklyn Museum’s new exhibit, We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women 1965-85 seeks to change that.

Highlighting the important work of Black women artists, the exhibit explores the political, social and cultural works of art during the second wave of feminism. The diverse group of artists and activists of the time worked at the intersection of art, politics and social justice. With over 40 pieces of artwork, sculptures, photography, film and writings, the exhibit explores the work of a variety of women of color. The artists featured in this exhibition include Julie Dash, Vivian E. Browne, Linda Goode Bryant, Carole Byard, Elizabeth Catlett, Barbara Chase-Riboud, Ayoka Chenzira, Christine Choy and Susan Robeson and many more.

MacArthur Foundation winner — photographer Carrie Mae Weems’ — integral work is one of the high points of the exhibit. Weems’ first collection of photographs and photo-text art “Family Pictures and Stories, 1978-1984” was a direct response to the controversial report by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, which effectively blamed the deterioration of Negro society on a dysfunctional and weakened family structure.

Weems incorporated her own family from her hometown of Portland, OR to refute the Moynihan Report and create a realistic portrait of Black family life.

Brooklyn born artist Lorna Simpson is well-known for her photo-text artworks. During the 80s and 90s, Simpson’s work was displayed all over the country. Simpson’s “Waterbearer” piece from 1986 is featured as a representation of the work of Black women. The photo is of a young girl pouring water seemingly without a care in the world. The text below reads “She saw him disappear by the river, they asked her to tell what happened, only to discount her memory.” Simpson most recently created the artwork for Common’s album Black America Again.

Toni Morrison’s seminal piece, “What the Black Woman Thinks About Women’s Lib,” in New York Times Magazine is also featured. The piece explored Black women’s unique relationship with women’s lib. The text is one of the first pieces to dissect white feminism and Black women’s apprehension to the feminist movement of that time.

In 1971, Morrison said, “There is also a contention among some Black women that Women’s Lib is nothing more than an attempt on the part of whites to become Black without the responsibilities of being Black.”

The importance of that text is understated. It reads though it had been written today and the original magazine is on display.

Black artists of the time created the Just Above Midtown (JAM) gallery to display the work of Black artists. Filmmaker Linda Goode Bryant and artist Janet Henry began producing the Black Currant magazine to document the experimental work of the artist community whose works were featured in JAM. The magazine was the first of its kind to show the vast and exceptional tapestry of Black Art. Black Currant later became B Culture with the early works of influential writer Greg Tate.

Organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Family Senior Curator of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, and Rujeko Hockley, the multimedia exhibit features films, video art, photography, paintings, sculptures and more. The exhibition is the first of its kind to primarily focus on the voices and experiences of women of color during this pivotal moment in history.

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 will be on display at the Brooklyn Museum from April 21 to September 17, 2017.