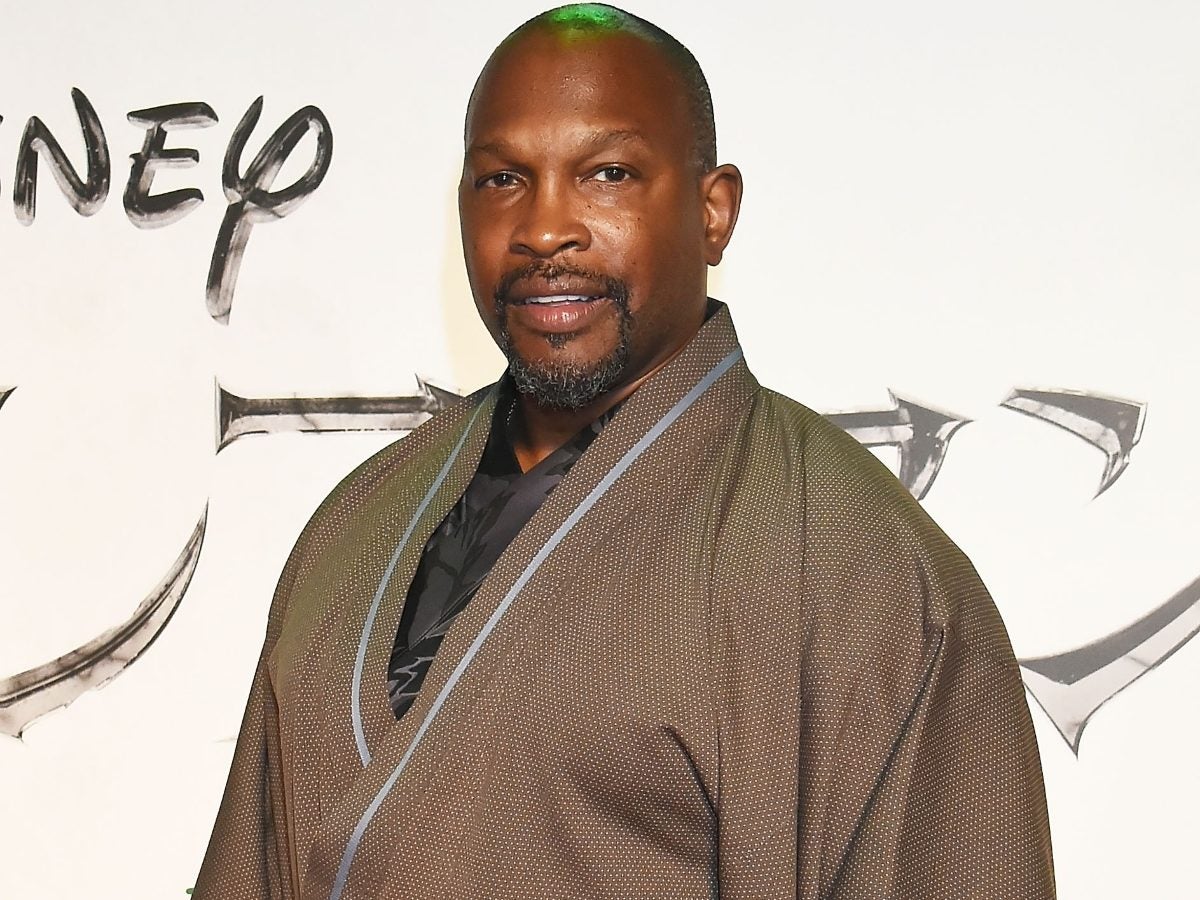

When classmates used words to “play the dozens” Chaz Guest dominated through pen and paper. “I just used to draw caricatures of everybody,” the self-taught artist told ESSENCE. “I used to win every time. ‘Cause if you had a big head or big ears, it was over.”

Drawing helped him communicate with “a very severe speech impediment.” His “nine sisters and brothers” made him feel safe to express himself as desired. “I always felt that I was protected and I always felt that I was respected and cared for. I don’t say that enough, but that’s actually the truth.”

He doodled constantly, even as the impediment’s symptoms subsided. “I really enjoyed coloring with crayons and using my imagination, which was huge. And I never thought that I would become an artist one day, but that’s what was in the plan.”

“I would draw on anything if it didn’t matter, napkins, even,” said Guest.

His friend mounted a 1987 drawing he completed after a night at the famed jazz club Village Vanguard left him “mesmerized” with Shirley Horn.

“It’s 2022 and you believe he still has that napkin framed up,” he asked as a stream of laughter briefly interrupting the memory.

Seizing the chance to acquire some of his vision was a smart move. According to the New York Times, Guest’s work has been collected by the Obama family, Oprah Winfrey, Tyler Perry, Herbie Hancock, Angelina Jolie and a number of prominent arts patrons. Being a visual communicator empowered him to become a better critical thinker. He questioned what he saw routinely.

“I was very cognizant of our history, here in America,” the artist said.

His curiosity “started like relatively early, I think about 13 years old.” Something about the scale of the imagery used in his education did not sit well with the pensive teen. He contemplated the sources behind classroom materials during rides to gymnastic meets long before encountering a paintbrush.

“I’ve been very cognizant of the fact that someone else was constantly writing our narratives,” he continued.

Narratives determine which artists are collectively deemed ‘important’, which stories are worth preserving for the historical record, and which musical artists deserve to receive a mainstream push. He maintains strong opinions about what is pushed to the forefront and expressed confusion at “how people can be sold on referring to us as the N word,” and “how successful you can become by being so derogatory to our race.”

He recalled seeing stereotypes like “step and fetch it stuff,” in his childhood. “It was horrible coming up, watching that.”

“It’s hard to get up over that, up on top of that,” he continued. “That’s why it’s so important for you to write your own narrative.”

Guest observed how Black people erecting their own spaces to do rarely penetrate our culture’s collective memory. “When we wrote our own narrative, we never had the power to have it matriculate through to the channels of history,” he said.

“When you’re sitting in class and they start teaching you about world’s history and they draw Africa really small in comparison to the United States right? At that one moment you’re now being told how inferior sort of, even in size that Africa is, which is totally untrue.”

He seeks to shift cultural narratives through figure portraits. His paintings depict historical figures with deep reverence, never failing to nod at the movements that birthed them in the details. No one who poses for him sits there alone. Stories of sacrifices, celebrations, and strife live in each stroke.

Guest has immortalized groundbreaking ballerinas, iconic photographers, international dignitaries, tragically slain children, unappreciated servicemen, and enslaved peoples with the same level of respect and appreciation. He was inspired to fight what he deems as misrepresentation by the activism and resilience of people like Paul Robeson who faced severe scrutiny for his efforts. He spent years, “watching him just fight back with such dignity and, and strength and power.”

“Paul Robeson’s my hero,” said Guest. “He really put me on front street as far as paying attention to what was going on in our lives as African Americans in this country.” He is also inspired by his birthplace of Niagara Falls and European travels (his first gig was a foreign magazine cover that reportedly impressed Christian LaCroix.)m

He salutes the heroic Buffalo Soldiers in his first series at New York’s Vito Schnabel Gallery. The late Michael K. Williams, whose most recognizable role was portraying anti-hero Omar Little in HBO’s The Wire, posed for the series before his tragic death.The portraits are dignified.

Guest described his personal standard for the title. “I think bravery makes a person a hero,” he said, also citing “intelligence, and unending integrity.”

“There’s not many heroes that I see today,” he lamented. “It seems like everyone can be bought for a dollar.”

His statements arrive as the merits of ideals like Black excellence are being openly questioned. His work was valued by high-profile Black collectors for years but this latest show is part of an influx of exhibitions held on the other side of doors previously perceived as difficult to be wedged open by Black artists.

“Now we are living in a time of cell phones and George Floyd has really changed the scope of things. All of a sudden the other races kind of woke up to our atrocity a little bit,” Guest said.

“I probably wouldn’t even be at Vito Schnabel Gallery if it wasn’t for that tragic event that had taken place,” he stated plainly.

He focused more on what he wants to say than scrutinizing the shifting winds of the art world. His goal is to leave his sons and others’ children with strong images that present what he deems to be the truth about Black people.

“I paint the narratives that I think should be put forth. And, I hope that I can one day see that make a difference,” he said.

“The things that I paint will be my voice.”