At the dawn of the 21st-century, researchers at University of Wisconsin–Madison and Texas A&M University sought the opinions of 137 scholars of American oratory on the best speech of the 20th-century. The experts were asked to evaluate the silver-tongued on the basis of social and political impact, and rhetorical artistry. The top spot went to Dr. Martin Luter King Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” speech, delivered of course, during the August 1963 March on Washington.

Of the #1 declamation, Martin Medhurst, professor of speech communication at Texas A&M said, “{King’s} eloquent vision of a day when his own children ‘would live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character’ persuasively articulated the American dream within the context of the civil rights struggle.”

Dr. King’s speech is a foundational text of the American experiment, but the words were not handed down from on high. They were written over a number of years, the speech and its themes evolving out of a variety of sources beyond the Holy Bible, “My Country ‘Tis of Thee,” and the Emancipation Proclamation. Even the exalted “I Have A Dream” repetition was inspired by a fellow preacher, Prathia Hall, an activist who led a prayer group in Sasser, Georgia on September 10, 1962, the holy ground where the Mount Olive Baptist Church stood a day prior. It was burned to the ground by the Ku Klux Klan. Hall watching the house of worship reduced to nothing as no firefighters showed up to save Mount Olive.

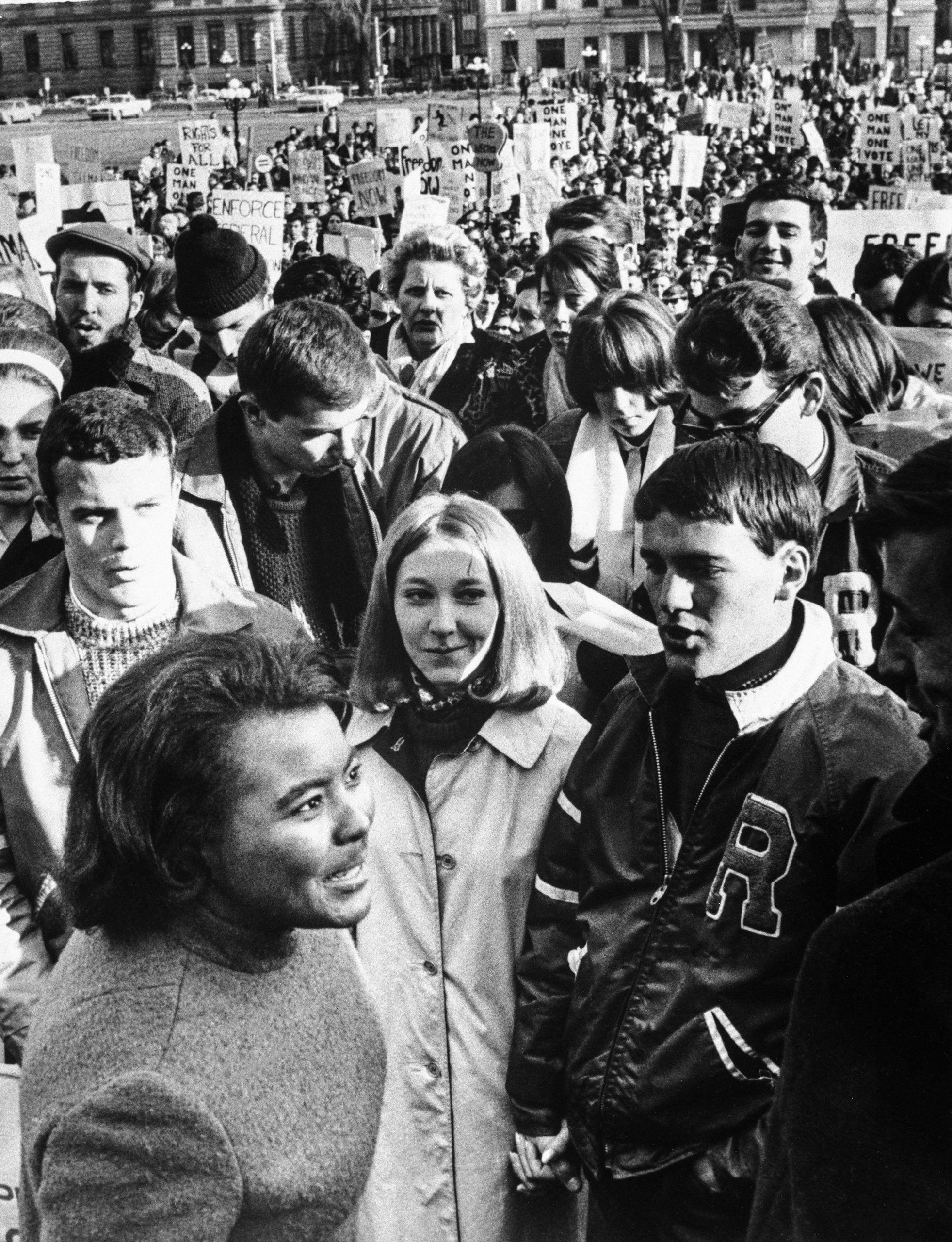

The church was a meeting place for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which Hall joined in 1962. She was the first female field officer in rural Southwest Georgia, which included Terrell County, a.k.a. “Terrible Terrell,” a.k.a. “Tombstone Territory,” a dark nod to the omnipresent violence activists faced. The local sheriff and his lackeys menaced both meetings and masses and held particular enmity for “outside agitators” like Hall and her organizing partner Rev. Charles Sherrod. On September 6, three days before she would plant the dream seed in King’s mind, Hall suffered a mild wound when segregationist night riders shot up the home where she was staying.

Amidst the rubble, Hall led the vigil attended by 50 African-Americans including Dr. King and Rev. James Bevel. At 22, Hall had only recently graduated from Temple University with a degree in political science, but she was a civil rights veteran. She immersed herself in the principles of nonviolence during high school at the Fellowship House, a social justice organization in her hometown of Philadelphia, PA. While in college, she was arrested attempting to integrate Barnes Drive-In, an Annapolis restaurant next to the State House, for which she did jail time. Hall also knew from the pulpit, as her father founded the Mount Sharon Baptist Church in 1938. (Rev. Berkeley Hall considered Prathia his successor, which would come to full fruition in 1978 when she took over.)

Hall was renowned for her oratory skills and considered to be a pastor of the civil rights movement in her own right, long before she officially followed her calling. At Mount Sharon, Prathia’s mother Ruby had children perform in front of the congregation, so her public speaking started young and became her calling card. Years later, SNCC secretary Judy Richardson was moved to tears transcribing the audio tape of a sermon Hall gave in Birmingham describing her as “a woman who could absolutely magnetize a mass meeting…such a command of the language.” She was an SNCC spiritual leader in every way, and always quick with the Word. Fellow SNCC members teased her as Prayer-thia Hall.

Dr. King had known Rev. Hall through the Fellowship House and their mutual commitment to social justice. By all accounts, he was enamored with Prathia’s gifted oratorical skills, and they were both featured speakers at the first anniversary celebration of the Albany Project. The Mount Olive vigil began with the gathering joining hands in quiet song. Claude Sitton of the New York Timessaid the group sang “We Shall Overcome” as “a wisp of smoke rose from the ashes of the church… The whites in the automobiles that shuttled slowly past looked on and said nothing.” Following the song, Hall delivered a prayer that included the lines “Lord, we’re going to be free. We want to be free so our children won’t have to grow up with their heads bowed.”

Throughout the prayer, Hall also repeated the phrase “I Have A Dream,” followed by individual calls for racial justice and equality. The specific things Hall called for have been lost to the annals of time, but they certainly made an impression on her friend Martin Luther King Jr. Here is Hall biographer (and fellow woman of the cloth) Courtney Pace’s account in Freedom Faith:

After the service, King sought and received Hall’s permission to use the phrase “I have a dream” in his own preaching. Hall was a fairly private person in general and certainly not an attention seeker. She did not boast about her connection to King, though, later in life, when friends asked about her role in “I have a dream,” she confirmed that King adapted the phrase from her use. She was quick to say King made the speech his own and did not plagiarize her.

For years, rumors persisted that Hall contributed the immortal phrase, but modesty at her role in King’s masterpiece kept it under wraps. Years later, Rev. Bevel would tell historians that yes, Hall’s oration at Mount Olive was the inspiration. Since there is no official documentation, audio tape, or handwritten eyewitness notes, some scholars remain suspect, although as Pace notes in her biography:

Whether she was his only source or merely the spark that culminated years of influence, it was only after personally witnessing Hall’s dream in Southwest Georgia that King started using the phrase in his preaching.

A year later, Hall moved on to Selma, where she bore witness to the brutal aftermath of Bloody Sunday. The violence changed the course of her life. In an essay about the fallout from the horrific events on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, she wrote, “This was a theological crisis for me. I went into a period of very deep silence after that. I withdrew. I was deeply traumatized. I soon left the South.” She was conflicted, but she remained committed to nonviolence. In 1966, as SNCC began to waver on those principles, Hall left the organization.

Hall married Ralph Wynn and fulfilled her destiny to join the ministry. She spent the rest of her life in church and the classroom. In 1977, she became one of the first African-American Baptist women ordained by the American Baptist Churches and was the first woman accepted into the Baptist Minister Conference of Philadelphia and Vicinity in 1982. She reached the mountaintop of academia as well, earning a Ph.D. from Princeton Theological Seminary in 1997. Fittingly, she would go on to hold the Martin Luther King Chair in Social Ethics at the Boston University School of Theology.

Ebony named Rev. Prathia Hall Wynn one of the “15 Greatest Black Women Preachers,” with a quote from Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright of Chicago saying she is in “a class of her own” who “lifts the gospel to new levels, lifting hearers simultaneously with an understanding of an awesome God that is unparalleled.” Hall died of cancer on August 12, 2002 at the age of 62. Her life and legacy are secure, as a committed activist, a devoted theologian, a brilliant speaker, and the unheralded muse behind the most beatific lyrics in the Greatest Speech in American History.