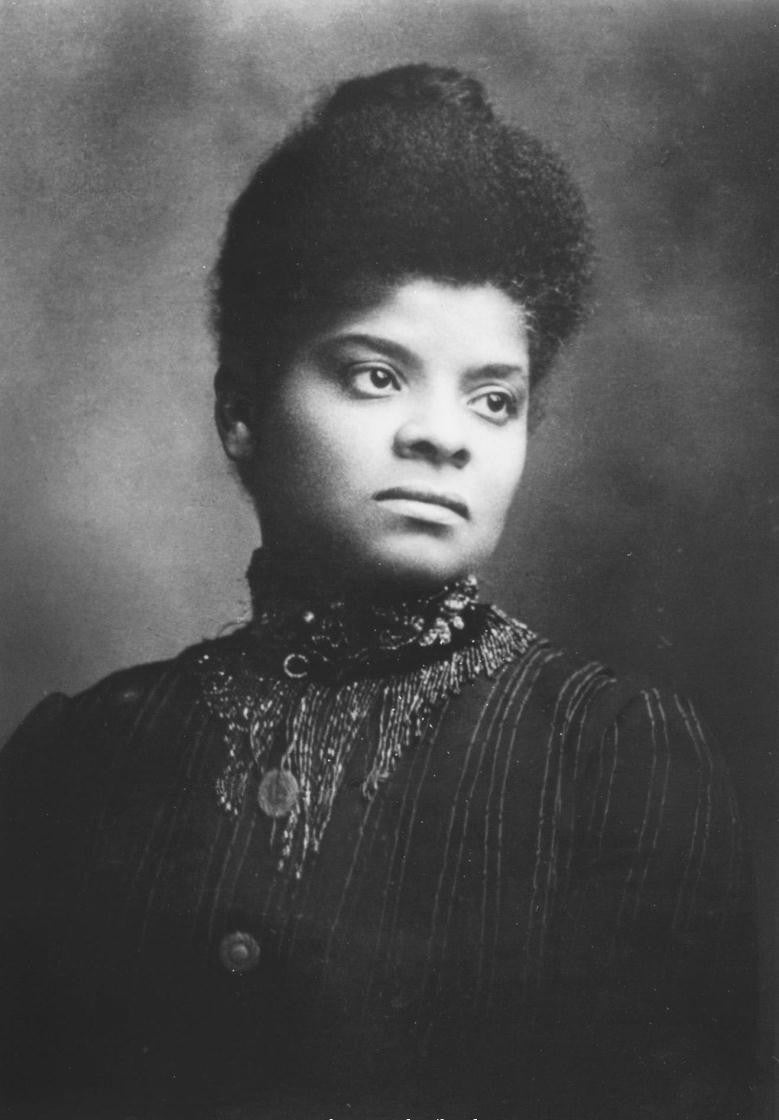

Ida B. Wells once said, “The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them,” and the journalist and activist spent her entire life attempting to do just that. This year, Wells, who died in 1931, would have been 156, and thanks to an effort to erect a monument in her honor in Chicago, her life and work are finally getting the respect it deserves.

In spite of her tireless advocacy for Black Americans, far too many people don’t know why Wells was such an important and integral figure. So here are 5 things to know about Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

1. Ida B. Well was born into slavery.

Before she became America’s foremost anti-lynching activist, Ida B. Wells was born into slavery on July 16, 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Like many Black Americans in bondage, Wells was freed by the Emancipation Proclamation in 1865. After gaining their freedom, Wells’ parents–James and Elizabeth Wells–became interested in helping Black Americans advance through political power. They attended speeches, lectures, and supported several Republican candidates during the Reconstruction period.

2. She was orphaned at 16.

During a yellow fever outbreak in her hometown of Holly Springs, Wells’ mother, father, and youngest brother died. Though she was just 16, Wells refused to allow her remaining siblings to be split up, so she raised them with the help of her grandmother. Thanks to Wells’ parents’ hard work, the family had a house and $300 in savings to tide them over. Still, Wells had to find work and eventually became a teacher at a local school for Black children.

3. Wells became an activist in Memphis.

After relocating to Memphis, Tennessee to be closer to her extended family, Wells found her voice as an activist. She was outspoken about both race and gender and eventually began writing a column for The Living Way under the pen name “Iola.” While she earned national acclaim for her writings, Wells was fired from her teaching position after criticizing the conditions of Black schools in the area. This didn’t stop her, however. Instead she co-founded the Free Speech and Headlight, and continued to write about the issues of the day.

4. The lynching of a friend inspired her most celebrated activism.

In 1892, Thomas Moss, a Black grocery store owner and friend of Wells, was lynched by a mob of angry whites after a confrontation in his store. Moss and two other men were killed, propelling Wells to speak out against the horrific practice. In a column in the Free Speech and Headlight, Wells urged Black residents to leave Memphis because officials in the town failed to “protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused by white persons.”

The slaying of her friend was the catalyst for Wells’ investigative reporting and her campaign to end lynching. Wells’ writing on the topic resulted in the offices of her newspaper being destroyed, but it didn’t stop her from reporting on the topic. In 1892 she published Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, a pamphlet on her research into lynching laws and how African Americans were targeted throughout the South. Three years later, she published a 100-page expose into the topic of lynching called The Red Record, which included graphic accounts of the barbaric practice and how it was levied against Black Americans.

5. Wells also fought for women’s suffrage.

While she is mainly known for her anti-lynching activism, Wells was also active in the women’s suffrage movement. In 1913, she founded the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago, the first group aimed at advocating for voting rights for Black women. That same year, she marched in the suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., but refused to march in the back where Black women were supposed to demonstrate. Instead, she marched with the all-white delegation from Illinois. The Alpha Suffrage Club educated the Black community on voting issues and were instrumental in helping to elect Oscar De Priest to the U.S. House of Representatives, making him the first African American to serve in Congress since Reconstruction.