In 2011, the United Nations declared October 11 the International Day of the Girl Child, in order “to help galvanize worldwide enthusiasm for goals to better girls’ lives, providing an opportunity for them to show leadership and reach their full potential.”

The movement was sparked by members of School Girls Unite, an organization of youth leaders advocating for the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals. Following their lead, President Barack Obama proclaimed Oct. 10 Day of the Girl in 2013, writing:

“Over the past few decades, the global community has made great progress in increasing opportunity and equality for women and girls, but far too many girls face futures limited by violence, social norms, educational barriers, and even national law. On International Day of the Girl, we stand firm in the belief that all men and women are created equal, and we advance the vision of a world where girls and boys look to the future with the same sense of promise and possibility.”

In a 2016 op-ed, First Lady Michelle Obama wrote that the issue of gender equity is not just a matter of policy; it is personal.

“Unlike so many girls around the world, we have a voice. That’s why, particularly on this International Day of the Girl, I ask that you use yours to help these girls get the education they deserve. They’re counting on us, and I have no intention of letting them down. I plan to keep working on their behalf, not just for the rest of my time as First Lady, but for the rest of my life.”

Yes, this is a day of both celebration and purpose. And in the midst of it all, the lived experiences of Black girls who, too often, are victimized, criminalized and erased, cannot—and should not—be overshadowed.

In 2014, President Obama launched My Brother’s Keeper, an initiative to address persistent opportunity gaps facing Black boys. In response, over 250 Black men and other men of color challenged Obama’s decision to focus solely on Black men and boys, and called for the inclusion of Black women and girls, stating in an open letter:

“MBK, in its current iteration, solely collects social data on Black men and boys. What might we find out about the scope, depth and history of our structural impediments, if we also required the collection of targeted data for Black women and girls?

“If the denunciation of male privilege, sexism and rape culture is not at the center of our quest for racial justice, then we have endorsed a position of benign neglect towards the challenges that girls and women face that undermine their well-being and the well-being of the community as a whole.”

The African American Policy Forum, founded by Kimberlé Crenshaw, Professor of Law at UCLA and Columbia Law School, co-author of Black Girls Matter: Pushed Out, Overpoliced and Underprotected, and Say Her Name: Resisting Police Brutality Against Black Women, amplified the letter and spearheaded the ‘Why We Can’t Wait’ campaign, which flowed from the reality that “any program purporting to uplift the lives of youth of color cannot narrow its focus exclusively on just half of the community.”

Specifically, for Black girls in the United States, the intractable scourge of white supremacy stains every corner of their lives; meaning they must battle misogynoir on both institutional and interpersonal levels at every turn.

In the study Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girlhood (pdf), co-authored by Rebecca Epstein, Jamilia J. Blake, and Thalia Gonzalez, the answers of survey participants provided anecdotal evidence of how dehumanized Black girls are in this country. According to participants:

- Black girls need less nurturing

- Black girls need less protection

- Black girls need to be supported less

- Black girls need to be comforted less

- Black girls are more independent

- Black girls know more about adult topics

- Black girls know more about sex

While the above racist and sexist perceptions are false, the institutionalized and systemic ramifications of such dangerous thinking are very real, with Black girls suffering the consequences.

Black girls are suspended and expelled from school more often than boys; Black girls are also 20% more likely to be detained than white girls their age.

According to the 2015 report “Gender Justice: System-Level Juvenile Justice Reform for Girls” (pdf), 84 percent of girls in the juvenile-detention system have experienced family violence; additionally, “[girls] in the justice system have experienced abuse, violence, adversity and deprivation across many of the domains of their lives—family, peers, intimate partners and community.”

Black girls are also less likely to receive any pain medication—and if they do receive it, it is less than their white counterparts.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that lower income women experience some of the highest rates of sexual violence. Black girls—and boys—live in the bottom fifth of the national income distribution, compared to just over one in ten white children, the Brookings Institute reports. And where there is Black poverty, there is police violence—with sexual violence being the second highest form of reported police brutality—and the state occupation of communities.

As Melissa Harris-Perry wrote in 2016, “Girlhood has never been a shield against the brutality of white supremacy.”

Still, we rise. Our Black girls are full of promise. They are leaders and scholars, artists and writers, singers and athletes.

But even if they were none of these things, they have the unassailable right to dignity, safety, love and joy, free of the burdens and pain this nation has piled on their backs.

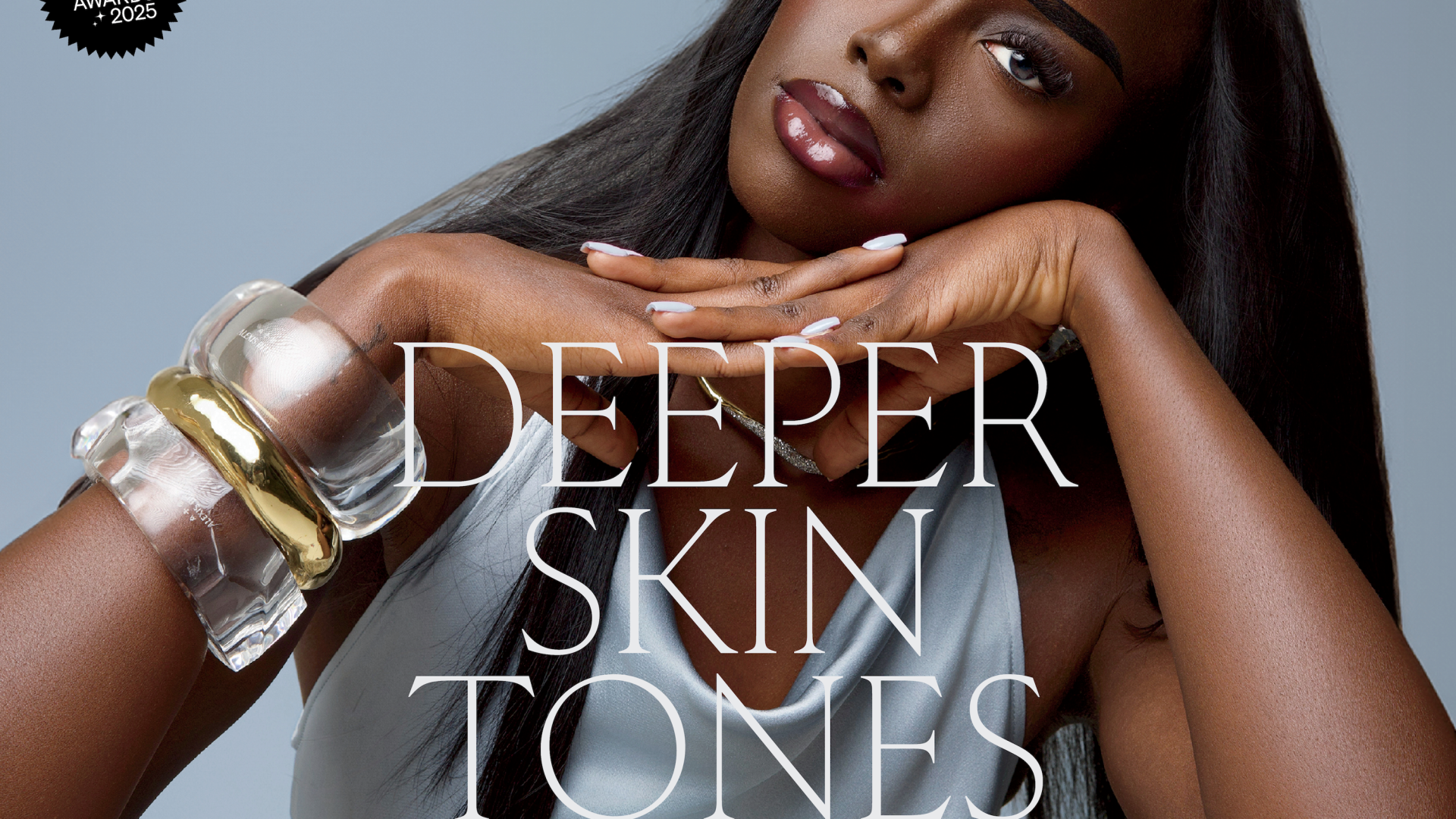

On this, the International Day of the Girl, ESSENCE is holding our Black girls in love, centering their experiences, demanding justice for all those harmed—and celebrating and protecting the fire that burns in each and every one of them, despite this world’s attempts to extinguish it.

Click here to read about 21 Black girls and young women transforming the world.

—

In loving memory of Gynnya McMillen, Aiyana Mo’Nay Stanley-Jones, Hadiya Pendleton, Rekia Boyd, and Renisha McBride, and all of our Black girls whose lights were extinguished too soon.