When she was 2 years old, singer, actress and now author Janelle Monáe saw an alien in her backyard.

“I told my mom and she didn’t believe me. But I told my grandmother and she believed me, so I never felt like what I had seen wasn’t real,” Monáe tells ESSENCE. “It was real in my spirit, in my heart and I just kept with that. I kept with the understanding that there’s life outside of human form. There are androids. There are other aspects of the world that I want to get to—I want to encounter, I want to see. And I’m always eager to meet some new life.”

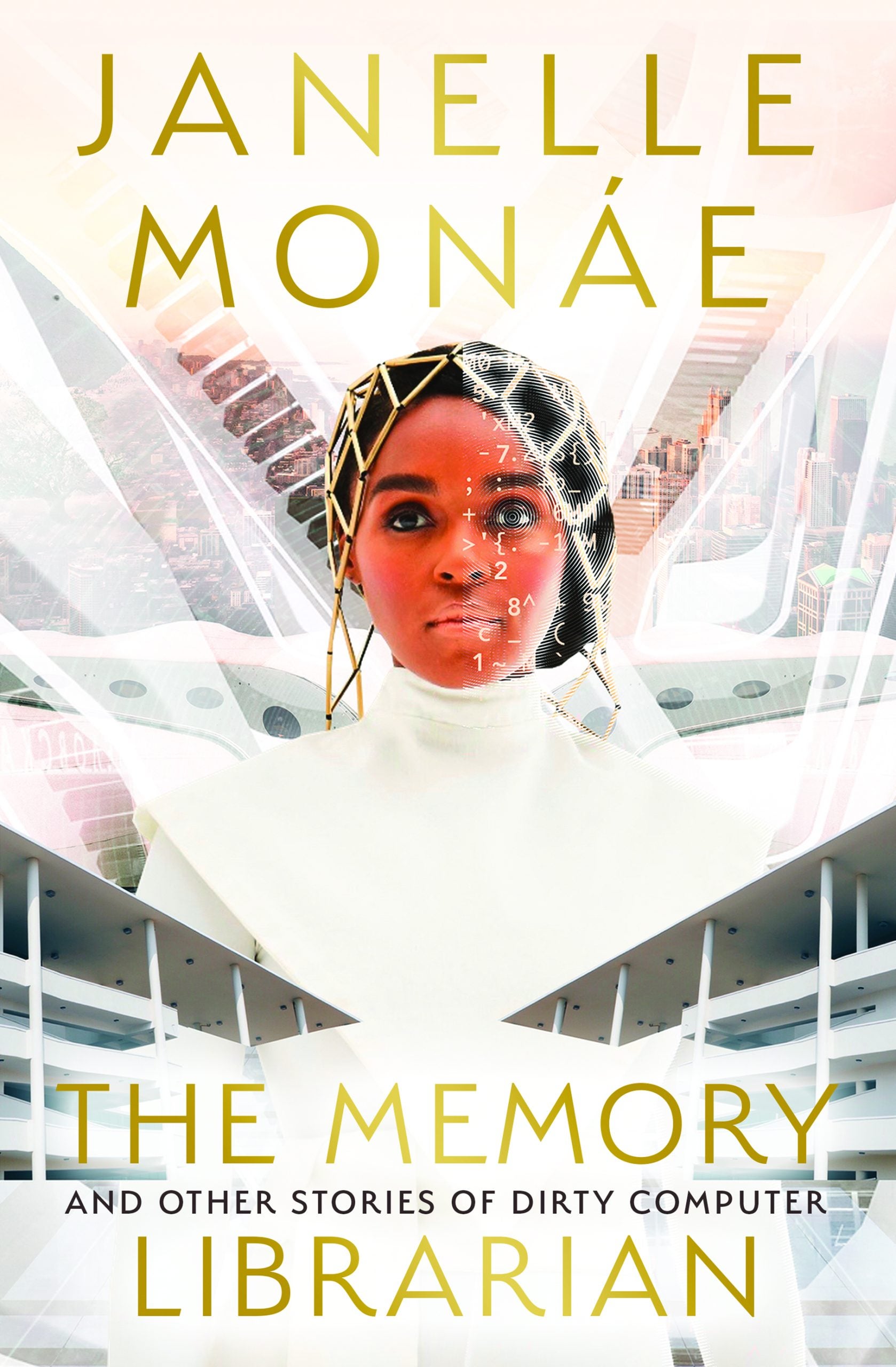

This early encounter is the reason Monáe has explored science fiction and elements of Afro-futurism in her art since the beginning of her musical career in the early 2000s and it’s the reason she’s partnered with other writers to release the new sci-fi anthology The Memory Librarian: And Other Stories of Dirty Computer.

The collection, which Monáe began writing in the early months of 2020, explores questions of queerness, love, gender plurality and liberation, all against the backdrop of memory and what it may look like in the future.

For Monáe, the anthology is a natural progression of her work and the realization of a childhood dream.

“I love storytelling. When it’s music, I’m telling stories through a video, a song, a live show. I’m telling stories through fashion. When I was growing up, I wrote a story about an alien talking to a plant. And through photosynthesis, they were preparing to take everybody in my grandmother’s neighborhood. So this has always been a dream of mine, to do it in an innovative way. Which is why this release is a collaboration between me and five incredible writers. All of them are Black and brown writers. One is nonbinary. They’re a part of the community that I feel has a lot to say and hasn’t necessarily had a large platform to say it.”

The collection features work from Yohanca Delgado, Eve L. Ewing, Alaya Dawn Johnson, Danny Lore and Sheree R. Thomas. Monáe believes the book and its themes are particularly salient given our current political climate.

“In The Memory Librarian there is a threat of censorship and I feel like that’s happening right now,” Monáe explains. “When you look at them trying to take critical race theory out of schools. Nobody wants to talk about slavery if it upsets a child, so they say. In Florida, they’re not wanting to even talk about the LGBTQIA and how these kids are identifying. That is a censorship that is happening now. It happens in The Memory Librarian, the protagonists are from marginalized communities. They do rebel. They do fight against it. It is going to be this book that predicts a potential future where the current sh-t we’re trying to ban is amplified in a way that our characters are fighting for the ability to live in our truth and to be seen in a nation’s larger story.”

In the titular story, Monáe collaborated with speculative fiction writer Alaya Dawn Johnson. The protagonist is a woman who is in charge of holding everyone’s memories. The story explores her quest for love. Describing the tale, Monáe addresses the potential conflict: “What does it mean when you want to fall in love but you know everybody’s secrets?”

Monáe was interested in exploring memory with this collection because of the ways in which our memories shape our identities.

“Memories define the quality of our lives. Without our experiences who are we? Without our memories, what kind of life do we live? I believe that memories are better shared with others. And I also believe our memories help us determine how we want our future to be. If our ancestors didn’t remember everything that happened to them, how would we know what to fight and advocate for for the future?”

With Monáe’s production company, there are talks to bring the stories to a more visual medium. But for now, she hopes the book serves as encouragement for those who need it most.

“I hope this book will be a beacon of light,” Monáe says. “Even though it may be banned in certain schools, I pray that the right kids find it. The right adults find it. The right parents find it and they look at it as a source of hope and inspiration to continue the good fight.”