On May 15, 2010, sixteen-year-old Kalief Browder, a Bronx, New York resident was arrested while walking home from a party for allegedly stealing a backpack. Though he was never convicted of the crime, Browder would spend over the next one thousand days of his life locked away on Rikers Island, being beaten, starved and tortured. Browder spent eight hundred of those days in solitary confinement before he was finally released, with all charges dismissed, over three years later.

A victim of a broken justice system, which cares little for impoverished people of color, Browder was unable to escape the things that he saw and experienced while at Rikers. On June 6, 2015, at the age of twenty-two-years old, Browder hanged himself at his home. The day before, he told his mother, Vendica Browder, “Ma, I can’t take it anymore.” At the time of his death, Browder’s story was making waves across the country. Now, with their compelling, six-part documentary event series, TIME: The Kalief Browder Story, Spike and The Weinstein Company are finally giving Browder the voice he so desperately wanted. This comprehensive look at his life, case, and incarceration at Rikers allows Browder the opportunity to speak for himself.

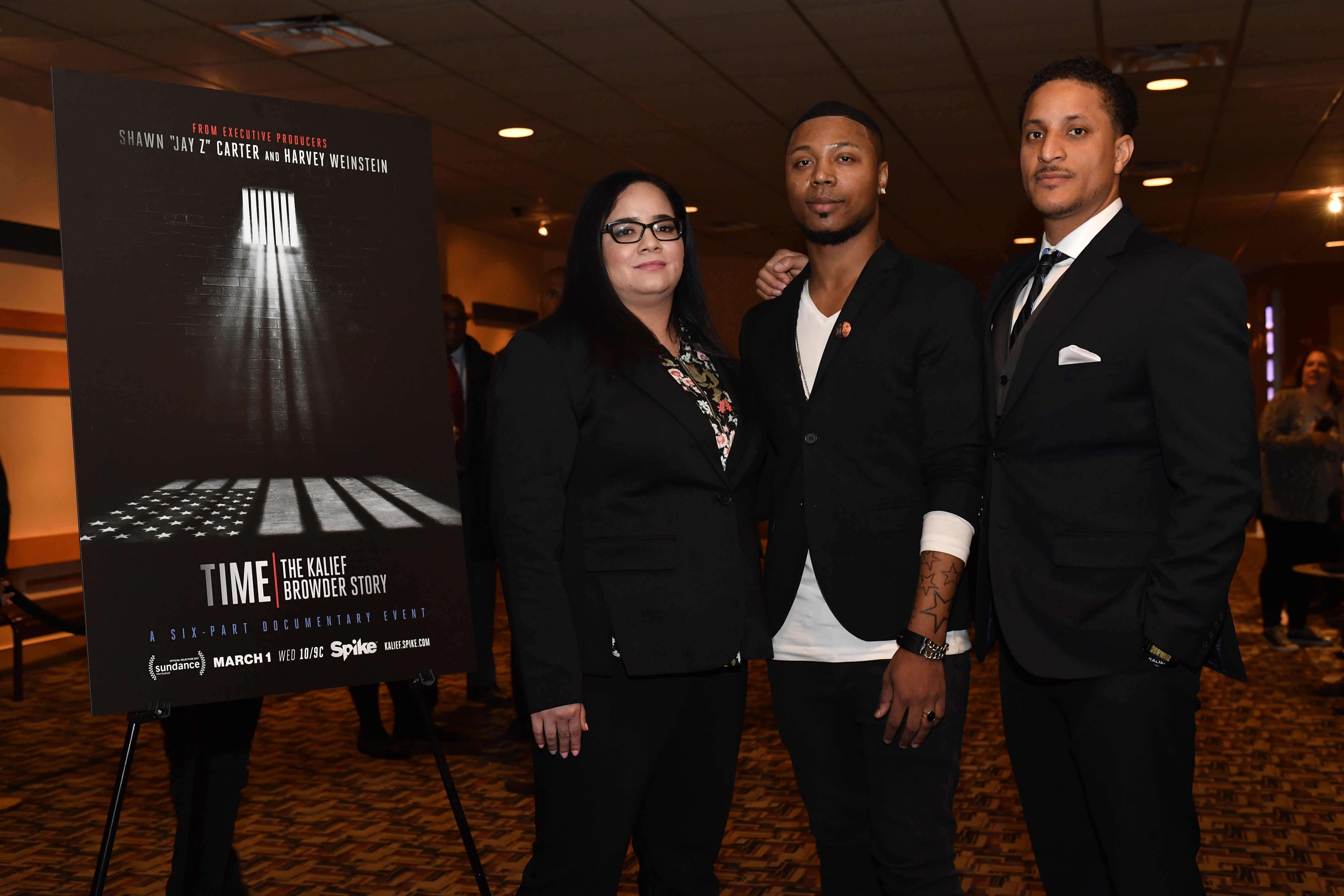

The evening before the series debut, ESSENCE caught up with Kalief Browder’s siblings: Nicole, Deion, Kamal and Akeem Browder, his lawyer Paul Prestia and filmmakers, Jenna Furst and Nick Sandow for a special screening and Q&A in New York City. Bronx City Council member Ritchie Torres moderated the panel.

Ritchie Torres: For the Browder family, can you give us a sense of who Kalief was as a person?

Nicole Browder: Kalief was a normal person like all of us. He was a happy kid, a silly kid; he was very smart. He always stood up for what was right. He was hardheaded and very playful. We picked on him a lot of the time because he was the youngest. Before he went to Rikers, he was a normal teenager getting to know who he was.

Deion Browder: One thing I will always remember about Kalief was how energetic he was. He was always into sports. He always wanted to try new things. He would do a lot of things to stand out as if to say, “Hey, I am here!” But, he was just a fun and energetic person, and he brought life to everyone around him.

Kamal Browder: He was always the competitive type. I brought a game called NBA 2K, and his team used to always be the Portland Trail Blazers. I don’t know how he found out who Clyde Drexler was, but he used to always call him Clyde the Glide, and he used to do insane dunks to make me mad.

Akeem Browder: Kalief was my younger brother, and you look to your younger siblings, and you want to protect them. He was just a kid. I mean no matter how old my younger brothers or my sister gets, they’re kids to me.

Torres: From celebrities to the media, to everyday people, the response to this story has been overwhelming. How would Kalief and your mother Venida respond to all of the attention that this story has received?

Nicole Browder: Kalief would be ecstatic, because one thing he did say is, “Nobody cares; they’re not going to care.” If he were here, he would be very happy but also still struggling. I remember my mom asking me, “When is the trailer coming out?! I can’t wait to see the trailer.” When it did come out, she was no longer here with us. I think we made them both very proud. I want to thank everyone who was involved. We didn’t think this was going to get any bigger than what we started with. So I’m very grateful, I really am.

Akeem Browder: My mother held us together, but she was very much a softy. It might be difficult for me to watch, but I’m compelled to sit here and watch because I want to see my mom again. I want to keep on seeing her. But, she wouldn’t be able to sit here and watch this.

Deion Browder: I want to second what my sister said and say thank you so much to everyone who was involved. You gave my mom hope before she passed. You gave her what we wanted for her, which was happiness. My mom is a great inspiration to me; they are both role models in my eyes. Kalief accomplished so much, and I know he would be proud of what we are doing today, because, like my sister said, he never thought his voice would be heard by anybody. This would be so surprising to him; so shocking to him to see how many people took an interest in him. For my mother, like Akeem said, it would be hard for her to sit here and even see what he went through. What he told her is one thing, but to actually see it would have put her through so much pain.

Torres: Even though Kalief was never convicted of a crime, he spent three years in Rikers. It’s unimaginable to most of us. Did Kalief ever communicate to you his struggle for survival during those three years?

Akeem Browder: Kalief was a private person. I was there. I was literally a resident at Rikers at one point, and then I ended up working on Rikers as an engineer. To speak to anyone who hasn’t been there, I would think to myself, “I sound crazy! No one is going to believe this.” We shared that, so [Kaleif] opened up with me at points. But to share with anyone else was kind of hard. So no, Kalief really didn’t speak much about it.

Nicole Browder: One time I went to visit my mom. I looked outside later; in the front, we have a driveway, and Kalief was walking in a square. I said, “Ma, what is he doing?” She said, “That’s what he did in his cell.” So, for me personally, when I saw Kalief it was like walking on eggshells. I didn’t want to approach him about it or talk to him about it. I didn’t want him to relive that. Like Akeem said, he was very private; he’s always been very private. I felt the best way to handle that was to avoid it. From before he went to Rikers and afterward, he was two totally different people. It wasn’t my brother anymore. I would look him in the eye, and there was nothing there, to be honest. But deep inside, Kalief fought really hard. He actually went and got counseling. He went down to the doctor and said, “Hey, I need some help.” He tried to live a normal life.

Deion Browder: My experience with Kalief in being a private person was going from being able to be free in the house to being enclosed. After he came out of Rikers, we lived in the shadows. He wanted nothing from the outside to be inside, so, we lived in the dark. He closed the shades. He didn’t want the TVs on; he would throw his TVs away because he always thought someone was talking to him on the TVs. Whenever he had a conversation with me, I had to close my phone and turn off my laptop. He assumed people were listening to him on any electronic device. It was tragic. I had to physically lock myself in the room because that’s how much he would lash out, punching walls, going crazy. It was a lot to deal with, just physically being in the house with him and not knowing how to handle that. He never wanted to speak to anyone about it. You had to literally wait for him to come to you. You could not ask him questions. If you did, he would get aggravated.

Akeem Browder: I just really want to give credit to Paul Prestia, Kalief’s attorney. When no one else wanted to step up and take the responsibility to represent him, he took on Kalief’s case. Eleven different attorneys said he had no case. One even said, “It’s not worth it, it’s not that much money.” We didn’t come for money, we came for justice, and this man stepped up.

Paul Prestia: I was proud to represent Kalief and of course Venida, but more importantly to be his friend and give him guidance and advocate for him. I think that’s part of being an attorney. It felt like the right thing to do, to take him under my wing. Unfortunately, it’s bittersweet that he’s not here today, but I told him many times that he was a hero when he was alive. I feared that he would do something to himself at some point and I just tried to get him to appreciate that there is so much to life. He should be here with us tonight, celebrating his life and his legacy.

Torres: Kalief was a private person who leaves behind a public legacy. So, how should the world remember Kalief, what is his legacy?

Prestia: I think Jay-Z said it best; he’s a prophet. This is Kalief’s movement. The movement for criminal justice reform that we see today, it’s here to stay, and Kalief is the reason why. All of the reforms that have come from this, they all started with Kalief in 2014. This is the stamp; this will bring awareness across the country and maybe the world as to what our system is like.

Nicole Browder: We would have never thought it would have gotten this big. He’s a legend now, my mom too. Like Paul said, Kalief was a hero. I’m so happy to be a part of Kalief’s life. I’m happy my mom adopted me or else I would not have had the chance to be a part of this family. So, when you think about your life being tough, and you say, “I can’t take it anymore.” I just look at my brother and say, “That’s when life is really hard.” What we go through today doesn’t matter because someone has it worse than you. So I live by that every day. Even though I’m older than Kalief, I look up to him and I talk to him a lot, and he brings me comfort. I know he’s in peace and that helps me move forward in life, and so is my mother.

Torres: Kalief symbolizes the urgency in criminal justice reform, so what needs to change in the criminal justice system?

Akeem Browder: A lot of problems played out in just the three years Kalief did time. One is the age of accountability. For a sixteen-year-old to be held in a torture chamber is ludicrous. We’ve been following the same draconian system for centuries. We’re locking up people and not getting a better result, that’s the definition of insanity. So, that needs to change. But let’s not kid ourselves. Wasn’t it illegal to do what we did to him in the first place? We should be saying enough is enough, get these kids out of there because no matter what, these are children. There needs to be a change in how we view our children. Mandatory minimums are also an extreme problem and the lack of a speedy trial in New York State. These are problems, but that’s a minuscule amount of problems because Kalief’s story is not rare. It happens to everyone. Stop and frisk puts 1,600 people a day in the hands of the law just walking down the street as a Black or brown person. Rikers is just one jail in New York; we have several others.

Torres: For the filmmakers, what inspired you to tell this story?

Jenner Furst: I’d like to pass it to Nick because he was really the driving force behind it. We read the story, but Nick was the one who jumped out and said we have to do something about it.

Nick Sandow: It was as simple as that. I had been working on projects in and around the prison system, and I read Kalief’s story, and when I heard of his passing, it just moved me. I called Paul after I saw his name in The New Yorker article and he called me back a couple of days later, and we talked.

Prestia: I remember that call. He called me two days after Kalief had taken his life. We talked, and he mentioned Jenner and a lot was happening at the time but eventually, we met, and it just felt right. The filmmakers had never even met Kalief, but he inspired them. I’m just grateful that it was the right people with the right vision.

Furst: When Nick called I said, “Of course, this man deserves the most epic of epic tales for what he went through.” I just felt like if the Browders were open to the brave journey and exploring their brother and their son’s life through the lens of this series, then we could do something truly incredible. At every step, Kalief was failed by a system. At every step of the way, there was some trap door that was revealing a different inadequacy that’s in place for the poorest among us. That’s what inspired us. Rarely is there someone who is so emblematic. It’s surreal to be a biographer, to be a filmmaker to tell a story about a young man whom you never got to sit with. I feel like I got to know him through his siblings and Venida and his friends. There was always another revelation or another story about what he did or how he stood up for something. Kalief’s story was so much more poignant and special, and it’s been the greatest gift, honor, and privilege. Thank you for trusting us.

Torres: What change do you hope to inspire with the film?

Furst: I think we are at a special crossroads right now. Tomorrow at ten o’clock, a hundred million Americans are going to have the opportunity to see this and be affected by it. Our partners at Spike have taken a brave and very decisive action to get this in front of a lot of people. We are able to take this story and provide it in a digestible form. Maybe then people will be able to understand the gravity of the situation. Maybe for one second they will envision Kalief regardless of their race or class or anything, they’ll imagine Kalief as their brother or their son. I think that stories really teach people, I think that statistics are very hard to digest and I also think the evening news is overwhelming and it doesn’t penetrate. The folks who want to go on a journey like this who may not have the understanding of the criminal justice system are going to learn something, but they are going to feel something very deep, and hopefully it will inspire them to make a change and not be apathetic. It’s very easy to be apathetic right now because we look around and we see what is happening on a national level and we’re scared. But, the reality is these types of reforms happen on a local level, they happen on a state level. You should take your DA and your judges more seriously. What happened to Kalief was not the doing of the President of the United States or his Congressmen. It happened on a very local level. Of course, there are systematic failings that led to it, but we need to get up and realize that we can make a change and we should do it right next to us, tomorrow.

Prestia: Despite all of these reforms there is an assumption of guilt. I think this series is going to bring back that presumption of innocence, which has kind of been lost.

Torres: How did you get the guards to speak to you?

Sandow: I have a neighbor, who is a former corrections officer, and I would talk to him about being a CO, and when we started filming, I asked him if he thought people would talk to us, and he gave me a set of phone numbers. People wanted to talk. Some didn’t, but for the most part, people wanted to talk.

Furst: I have to give Julia [Willoughby Nason] credit because she pushed for the humanization on the other side. We want to demonize the corrections officers, but that’s part of the problem. Van Jones speaks on this directly, later on in the series. There are folks on the other side that have a right to be humanized too. It’s a hard job; it’s a very complicated job. Not all of them are corrupt, not all of them are breaking the rules. It was important for us to provide an open forum for former corrections officers at Rikers Island to talk about what it meant to work there. There is a lot of things that are brushed under the rug that people don’t understand. There are high rates of breast cancer among female employees that are close to their pensions at Rikers. People don’t realize they are getting autoimmune diseases because there is toxic waste under the ground there, or the posttraumatic stress that the actual guards suffer. One of the things that was said to us was, “We’re doing time too. We’re just on the installment plan.” Look it’s a very complicated situation. Many folks are put in an environment where it brings out the absolute worst in them, and it’s not their doing. Many of them want a better life and they are serving, this is law enforcement, and many folks deserve respect for their service. But there are some, and the percentage is larger than it should be, who engage in such high levels of corruption and criminal activity that it would make your head spin. They turn the folks who went to work trying to serve into monsters. Kalief in his deposition did point out several COs who were nice to him and who cared about him, and if it weren’t for certain wardens touring, the starvation would have continued in some instances. This is stuff that you will discover later in the series. The “bad guy” is something a lot scarier than corrections officers. It’s about monetizing the poor; it’s about people who have made an economy out monetizing the poor.

Torres: How would you encourage young people who relate to Kalief, who are angry and who feel like the system fails them every day?

Akeem Browder: What we should be doing in the community is providing hope because right now there is dead fear and lack of hope. We want to bring awareness, but what I would suggest for them to do is start being active. There are many platforms. It’s not just going up to Albany and trusting other people with your life. You’ve got to also do something. We can only show this and hope that you all call and shame the departments that are taking advantage of our communities.

Nicole Browder: I would have to say that as a family we are very fortunate to be on a bigger platform. It takes a community; it takes a family. It takes reaching out, it takes speaking up, and it takes us talking about it, and not with a lot of anger because you never get your point across that way. It takes people who listen because these are people whose backs are against the wall. So, reach out, say something. Don’t be in the back seat waiting for things to come to you. Once we can come together, I feel like we can make a difference. It takes all of us to keep going forward. Once this documentary airs tomorrow, somebody else may come out and say, “I’m going to speak up, I’m not taking that plea when I go to court next week.” So, it starts a movement.

TIME: The Kalief Browder Story premieres Wednesday, March 1 at 10 PM on Spike