Bryan Stevenson, activist and author, is a man seemingly ordained to fight for freedom. The soft-spoken jurist is so purpose-filled that if he came here just to do his narrative work, or just to represent the least of those on Alabama’s state-sanctioned death list he would have lived an honorable life. But somehow, some way, this knowledgeable man of law and history as well as struggle and resistance knows what redemption requires: the whole truth. And so he works tirelessly to both narrate and change this great, violent, enduring American saga.

At 62, Stevenson, the founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), has been defending primarily impoverished Black people on Alabama’s death row for more than 30 years. His work and story were featured in the 2019 documentary True Justice and the film Just Mercy, starring Michael B. Jordan. There came a day, however, when Stevenson realized that working solely within the justice system wouldn’t be enough to bring about lasting change. “It was about 15 years ago that I began to fear that we would not win Brown v. Board of Education today,” he says. “I’m not sure our courts today would do something as disruptive as Brown in the current political climate.”

Stevenson says when he began to realize that the Brown decision had been accompanied by years of narrative work and decades of activism, he also realized that “we have to start talking more, outside the courts, about this history.” This is where his narrative work, which seeks to honor the truth about this nation’s legacy, began.

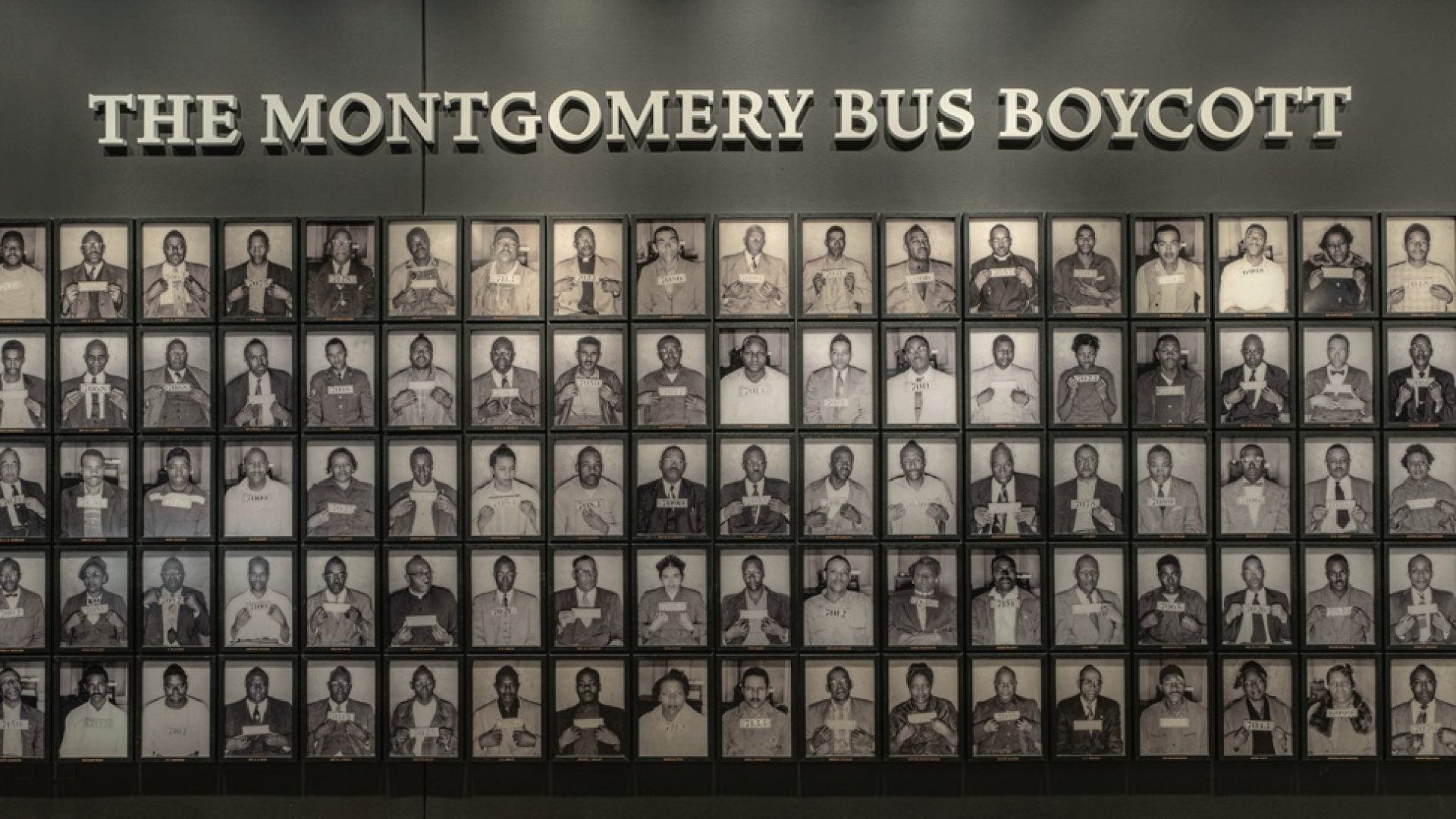

In April 2018, EJI opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice to document the nation’s horrific history of lynching Black people, and the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, in downtown Montgomery, Alabama. What Stevenson does so well, so beautifully, with both these sites is bear witness to the lives of those taken from us so violently, while also creating a space for catharsis and possible redemption. “There just aren’t museums in this country like this one,” he notes. “And I think the absence of truth-telling spaces about our history is a real vulnerability in American society.”

FIRST, WATER

The Legacy Museum, which has expanded to 40,000 square feet and now also includes a Black-owned restaurant, begins with one of America’s gravest sins, slavery, and connects those chains to the ones worn by millions locked away in cages under what we now term mass incarceration.

When you enter the museum, you are immediately immersed in darkness. In the simulated experience of a rocking ship, the terror is palpable. PTSD bubbles in the blood. You’re reminded of the 2 million or more who died in the passage across the Atlantic, taken by sickness or despair, jumped or thrown overboard. “This whole thing about the ocean and what the ocean represents is a relatively new understanding for me,” says Stevenson, who adds that he had never been to Africa until about 10 years ago.

“I went to Nigeria and a young lawyer met me—it was like one in the morning. And he said, ‘I’ll show you Lagos.’ And we drove around to all these places. I was so tired, and eventually he said, ‘One more place.’” Stevenson shakes his head ruefully, remembering. “We climbed over a concrete barrier to get to the beach,” he recalls. “It wasn’t a particularly attractive beach. It was the middle of the night. And we got there and just stood. He said, ‘I brought you here because I wanted to say I’m sorry. This is where we lost you.’ And I realized that I was standing on the other side of the ocean, for the first time in my life. And I am part of this community of lost children of that continent. And that consciousness really began to impact me.”

At the Legacy Museum, after experiencing the simulated rocking ship, you walk through a middle passage of sorts, meant to mirror the ocean floor. On either side of you lie beautiful African people. Men and women, aunties and babies, mommies and sistren, lovers, sons and friends—all sculpted by artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, and all lost, strewn and scattered on the Atlantic floor.

“We do things with water in this space,” says -Stevenson. “I think until people begin to get their mind around it, they don’t actually understand what it represents, and that’s part of why I feel it’s so important. We have a film in one of the theaters, in which people in Africa talk about what it was like to hear the stories of great-grandparents who were taken away, lost to the sea. They called them ‘the lost ancestors.’ And that connection is really important. So if we can find ways to talk about these aspects of history, new insights emerge.”

TRAVERSING OUR LEGACY

The Legacy Museum deftly uses technology, via holograms and videos, to “listen” to the enslaved and incarcerated. Stevenson notes that the exhibits also delve into the exploration of slavery’s economics, its brutality and sexual violence, Reconstruction, racial-terror lynchings, the Jim Crow era and mass incarceration.

Because the sister site to the museum is the national lynching memorial, with free shuttle service between the two, Stevenson says EJI now has the most comprehensive data in the country on lynchings—which at present count stands at nearly 6,500 dead African-Americans, whose vicious murders took place in nearly every state.

When it came to civil rights, Stevenson says he wanted the museum to tell a different story than had been told before—mainly because the fight is far from over, and there are clear connections between slavery and mass incarceration, and between lynching and the death penalty.

He notes that most civil rights spaces he’s visited “skew toward triumph—how in the end, the laws change and racism is hopefully over.” While he applauds this optimism, he is concerned that such accounts can set us up to believe we have accomplished more than we actually have. “So what we wanted to talk about was the intense resistance to civil rights, to immigration, to all those leaders,” he says. “Not just by Klan members but also governors and senators, legislators and judges who were saying, ‘Segregation forever!’”

Of course, there has always been resistance to any forward movement for Black folk. With today’s fervent dog whistles about Critical Race Theory (CRT) and the 1619 Project, Stevenson is clear that this resistance is part of a continuum in the American narrative. Yet with CRT specifically, he is flummoxed by the way it has been weaponized against people of color. “I’m a little surprised that someone could take a really complex legal theory, a way of thinking about the law, and turn it into a threat to elementary school kids,” he says. “It’s just sort of laughable to me.”

THIS FAR BY FAITH

And yet there is grace, even amid the intense emotions provoked by many of the museum’s installations. After the main area, a new reflection space honors around 400 people who resisted racial injustice, and a world-class gallery nourishes the soul with work from some of our most celebrated Black artists, including Glenn Ligon, Elizabeth Catlett, Alison Saar and Gordon Parks.

Stevenson’s core philosophy is that we are each far greater than the worst thing we’ve ever done—it’s part of why he’s spent so much of his career representing condemned prisoners and people in jails and prisons. He applies the precept to those who do us harm, too. “[In church], we are taught that the pathway to redemption and restoration and salvation requires confession and repentance,” he reflects. “We actually are capable, in this country, of talking honestly about this history and surviving—and not just surviving but getting to a better place.”

The veteran lawyer points out how much progress has been made in other areas, including domestic violence and sexual harassment. It’s been achieved even with drunk driving, after MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Driving) very effectively “forced a conversation” about consequences for operating a vehicle while intoxicated. In the same way, “we have to talk about this history,” he insists. “We have to model that we can actually tell the whole truth to each other and survive. In fact, the only way we can survive is if we tell the truth.”

Angela Bronner Helm (@GrlAbtUpTown) is a New York–based journalist and editor.

This article originally appeared in the January/February 2022 issue of ESSENCE magazine, available on newsstands now.