Monique Moultrie grew up like millions of Black women did, in the church. And like so many church girls, Moultrie was exposed to dangerous rhetoric from the pulpit: Gays were going to hell. God could not use gay people. They needed to change. She believed it.

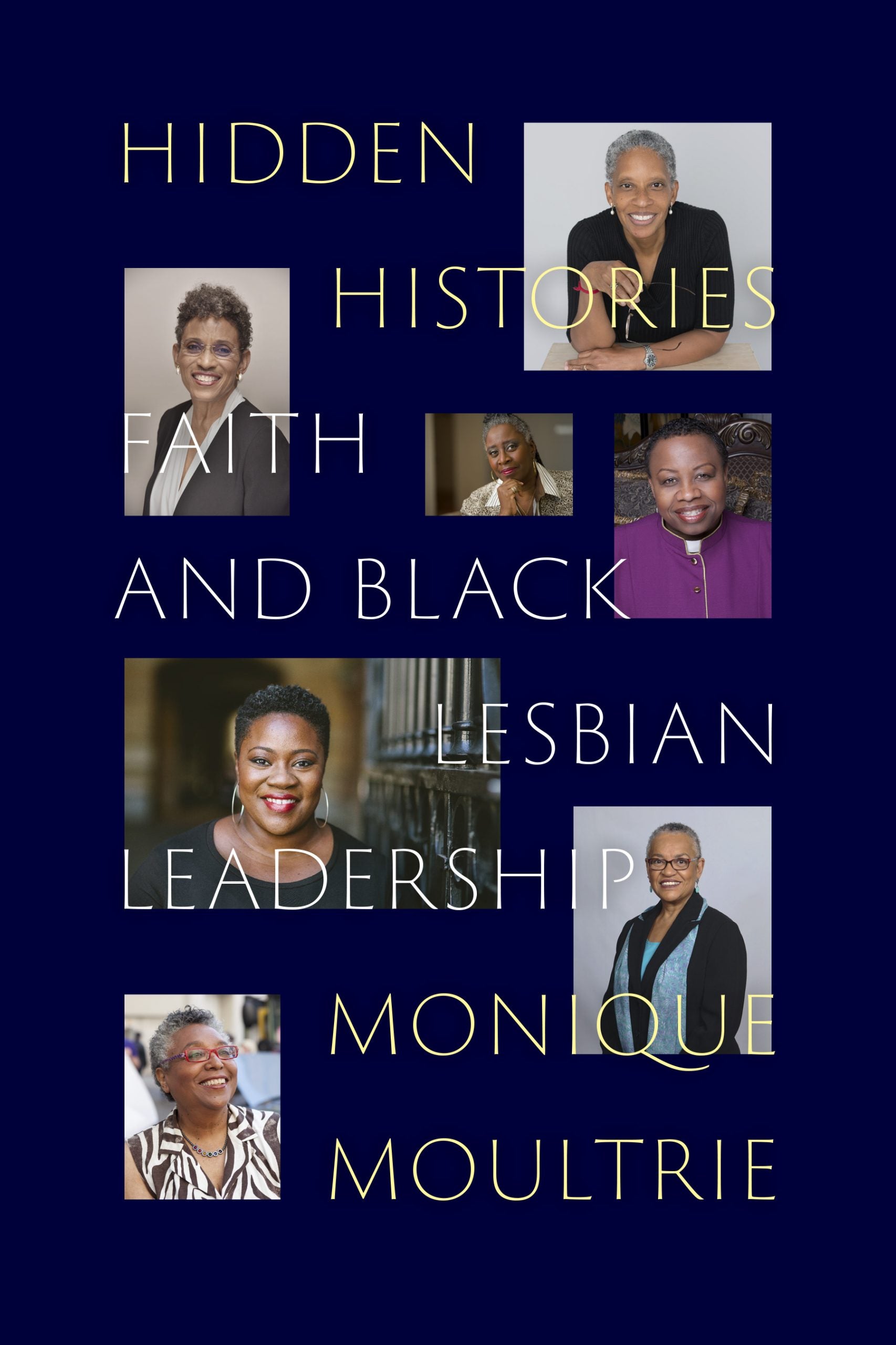

Eventually, as Moultrie matured, her experiences offered new perspectives. She witnessed the work queer religious people were doing in the world and spent years deprogramming her thinking. Now, as penance, she’s written Hidden Histories: Faith and Black Lesbian Leadership.

“That’s where the book started,” she says, “as a realization that I was wrong and I needed to publicly get right.”

Moultrie believes that sharing these women’s stories has the potential to change not only perceptions of the LGBTQ+ community but churches and their congregants too.

“Perhaps if we saw the work that was being done and the gifts that they bring to the community and the change they make possible, maybe we could have a different response: a non homophobic response, a non-transphobic response,” Moultrie tells ESSENCE. “And from there, a deeper calling, a sense that these women’s stories could change lives. They could change churches. They could change synagogues and religious institutions. And the more we could amplify their stories, the better the world would be.”

During her interviews with these lesbian church leaders, Moultrie was surprised to learn just how long they had been doing social justice work. Many of them had been leaders since they were still girls.

“Bishop Yvette Flunder tells a story of being an elementary school child sitting on the curb and kids coming to her,” Moultrie recounts. “She said it was like bees to honey. And they’d ask her, ‘What should we do?’ And she was able to tell them, ‘Let’s go pick up cans.’ That’s leadership being honed for good.”

While the public acknowledgment might not always be there, the church is familiar with the work Black lesbian women have performed from the beginning. In many instances, the church has been responsible for exploiting that labor. Moultrie says as the segment that accounts for the largest membership in Black religious spaces, Black women have to demand more.

“I think we often take less than we would ultimately want and definitely less than we deserve because we don’t think it can be any other way. Tradition stands in the way of it being any other way,” Moultrie says. She encourages Black women parishioners of any sexuality to ask themselves, “Are we in spaces that allow us to be fully who we are?”

Moultrie truly believes if you give women the space to wrestle, interrogate and think about the Biblical text, they’ll do the rest. “Free people free people,” she says.

But that freedom has the tendency to threaten traditional heterosexual, male leadership. With the pillars of patriarchy and homophobia erected so strongly in the Black church, it’s a wonder that Black queer women desired to stay affiliated with the church in the first place. Through her research, Moultrie found that once these women realized that God could use them, they brought the work they had been doing in the community back to the church house.

“God is calling them, this is God’s work that they’re doing in the world,” Moultrie says. “They should also be doing it in their religious communities.”

Many queer Black women had to undergo the same deprogramming as Moultrie to address their internalized homophobia.

“Dr. Renee McCoy was one of the leaders in the first Black gay and lesbian affirming denomination Unity Fellowship. She said that’s what their church did for years and years. Sermon after sermon was about ‘It’s okay to be gay, God loves you. God’s love is for everyone.’ They had to give that message enough times so that it sunk in. So people would keep coming week after week.”

In one of the endorsements of her book, Rev. Dr. Stacey M. Floyd-Thomas says it is imperative that sexual identity is essential to understanding the leadership styles of queer, religious Black women. Moultrie agrees.

“When we start giving language for people’s full identity to be present, it takes away the invisibility, the erasure of their actual work and their presence,” Moultrie explains. “It gives us a more complete record of who’s been in our communities and the long-standing presence of gay, lesbian and trans folks in our communities.”

Moultrie is concerned about removing erasure not just from an academic perspective but from a social one as well. She wants these women and their stories to show up when someone growing up in a small, conservative community Googles, “gay and Christian.”

“Their lives prove the ‘It Gets Better’ campaign and making sure that that is visible, it’s possible, and it’s something others can point to is a true gift,” Moultrie says referencing the nonprofit organization geared toward empowering LGBTQ+ youth . “We can’t just act like color, race, gender and sexual identity don’t exist. We’re all one in Chris. Yes, we are, but we also are individuals who have specific contexts and those should be celebrated as well. And understood.”

Moultrie says that understanding is particularly crucial now because she believes the future is queer. “The way in which these women that I interviewed lead is the sustainable model for the future,” Moultrie says. “These women have had to lead communally. I think that that’s not a bad thing. Grounding our religious communities in communities of need is actually what the church should be.”

Being ostracized from traditional church leadership, these women have turned to the expertise of various outreach groups, a practice that is not often replicated in the church.

“Senior leaders of the church tend to be traditional Black men. The senior leadership isn’t going to give them a pulpit or a space to talk about whatever social justice work they’re doing,” Moultrie explains. “There are younger and middle aged leaders that are going to give them that space. They tend to mentor and lead in that same way. They look up and down. They look at seniors who’ve been in the game for sixty years. They look at younger leaders who’ve been ‘out’ since they were eleven, advocating and they bring all of that.”

Because Black queer women have been so marginalized in the church, they’ve learned to work outside of the institution. Working outside of the church, Black women have been able to take on issues the church might ignore.

Moultrie points to Allyson Abrams as an example. Abrams was a pastor of a traditional Black Baptist church in Detroit, but when she married her wife, all hell broke loose. The church was split. Abrams eventually left and started a congregation in D.C.

In her new church, Abrams and her congregation are actively engaged in immigration reform. You might wonder why a Black American woman would care about immigration reform. But Abrams’ church is located next to an immigration rights group.

“They began to see some of the problems, legally, that y’all are having, are some of the problems queer people are having,” Moultrie says. “There’s this bridging of things, on paper, that might not look like they go together. When I say the future is queer, it’s not, ‘Oh, let’s go make more lesbians.’ That would be fine. But I’m saying let’s look at how they’re leading. It’s a more sustainable model than this one leader that we’ve hand picked that’s charismatic and then when they have flaws, the whole thing crumbles.”

For Moultrie, the future of church leadership is queer because there is a return to the community, a concern about the plight of our neighbors and a willingness to embrace congregants in their fullness.