On the June 1st taping of the weekly French late-night talk show On N’est Pas Couché (ONPC, loosely translated to “We’re Still Up” in English), French novelist and regular panelist Christine Angot stunned viewers by using the appearance of writer Franz-Olivier Giesbert and his upcoming Nazi-era Germany novel, Le Schmock (The Schmuck) to make jarring comments comparing the Holocaust to the Transatlantic Slave Trade and subsequent colonialism, significantly minimizing the latter:

“The purpose with the Jews during the war was to exterminate them, that is, to kill them, and that introduces a fundamental difference with black slavery where it was exactly the opposite. the idea was instead that they are in good shape, they are healthy, to be able to sell them and they are marketable.”

A cursory glance at the basic facts of the Trans- Atlantic Slave Trade quickly debunks the distorted falsehoods that Angot fabricated about the nature of chattel slavery, a centuries-long brutality with an immeasurable death toll. The additional insult to injury, however, lies in the audacity of any of the press within France – one of the pre-eminent colonizers of the Caribbean and Sub-Saharan Africa – making distinctions in the harms that were historically imposed upon Black people, while simultaneously imposing a cultural norm of rejecting to acknowledge the nuances of race altogether.

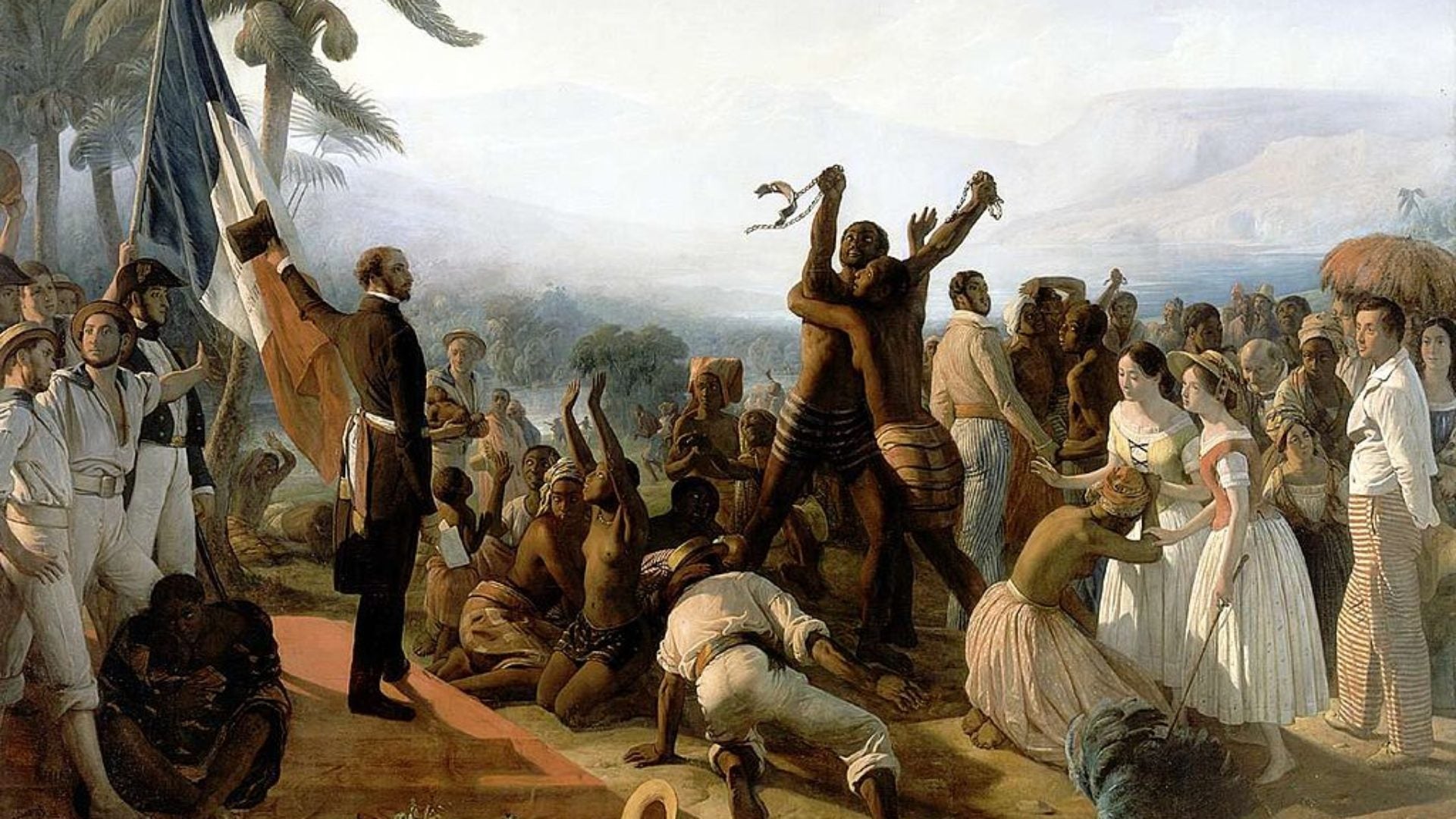

The largest slave rebellion in history, after all, was the Haitian Revolution – a transformative insurrection against the draconian rule of French overlords, who, despite Angot’s convictions, worked slaves so hard that half died within a few years of their arrival, and very few children lived beyond a few years of their birth on the island. As opposed to improving the quality of life, it was in fact more cost-efficient to bring in new slaves, leading to the highest death rates in the Western hemisphere – the Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion estimates that over a million slaves lost their lives at the hands of the French, exclusively on the state of what was then named Saint-Domingue.

While slavery may have been formally abolished by the French Republic in 1848, the French stranglehold of colonialism remained throughout the French West Indies and expanded in Francophone Africa, utilizing barbaric tactics to stamp out any attempts at self-determination well into the 20th century, and even in tandem with the tragic events of the Holocaust. It’s a circumstance that the esteemed Martinican writer and politician Aimé Césaire takes pains to examine in his seminal text Discourse on Colonialism:

“It would be worthwhile to study clinically, in detail, the steps taken by Hitler and Hitlerism and to reveal to the very distinguished, very humanistic, very Christian bourgeois of the twentieth century that without his being aware of it…he is being inconsistent and that, at bottom, what he cannot forgive Hitler for is not crime in itself, the crime against man, it is not the humiliation of man as such, it is the crime against the white man, the humiliation of the white man, and the fact that he applied to Europe colonialist procedures which until then had been reserved exclusively for the Arabs of Algeria, the coolies of India, and the blacks of Africa. “

Modern-day efforts continue to show a failure to reckon with the nature of what the true harms of France’s legacy has imparted on its Black Francophonie. In 2005 there was a disastrous attempt to put into law a mandate for schools to recognize the “positive role” of colonialism in history, to huge protests from citizens in the French West Indies. And while colonialism is formally over, the outre-mer, or overseas departments, remain intact, maintaining the last vestiges of France’s control of Black nations, from Guadeloupe and Martinique in the Caribbean to Reunion and Mayotte off the East African coast.

Presently, in the French National Assembly legislative building, there is a longstanding painting that is intended to celebrate the abolition of slavery in France – except the artist, Herve di Rosa, controversially applied what he insists is a race-neutral iconography but at first glance seems to draw immediate association to Sambo imagery or Tintin in the Congo: large protruding red lips placed over dark skin. In response, Mame-Fatou Niang, an Associate Professor of French Studies at Carnegie Mellon University known for documentary film Mariannes Noires, in collaboration with colleague Julien Suaudeau, started a campaign to have the painting removed from the government building, stating that “this ‘work of art’ constitutes a humiliating and dehumanizing insult to the millions of victims of slavery and to all their descendants.” In response, di Rosa – a white man – has dismissed this call to action as censorship of the right to freedom within the art form, no matter the context, with the National Assembly stating that they had no plans to take down the painting, irrespective of the feelings of France’s Black population domestically and throughout the outre-mer.

As part of Angot’s talking points on ONPC, she emphasized “c’est pas vrai que les traumatismes sont les meme, c’est pas vrai que les souffrance infligées aux peuples sont les mêmes. Et c’est bien pour ça qu’on doit être attentif, chaque fois, au détail, a la particularité”; it’s untrue that traumas are the same, that suffering inflicted on people are the same, and that’s why we must be attentive each time, to the details and particularities. She is absolutely correct: the specificities of our collective experiences are critical and important when exploring the impacts of our tragedies. Considering that, it’s even more unfortunate that she fails to recognize the need to apply any regard to the significance of the cumulative Black experience, especially as part and parcel of the country she calls home, before launching into an assessment riddled with inaccuracies in favor of advancing a particular narrative. If race continues to be a taboo topic in France, then history will never be confronted with the proper weight it deserves, and we will continue to be forced to untangle a web of competing myths while the reality of the Black French diaspora remains obscured.