“The first piece of steel I felt when I was a baby wasn’t a doctor’s stethoscope,” Fred Hampton Jr. shares with ESSENCE. “It was a Chicago police officer’s revolver as he pressed it against my mother’s pregnant belly.”

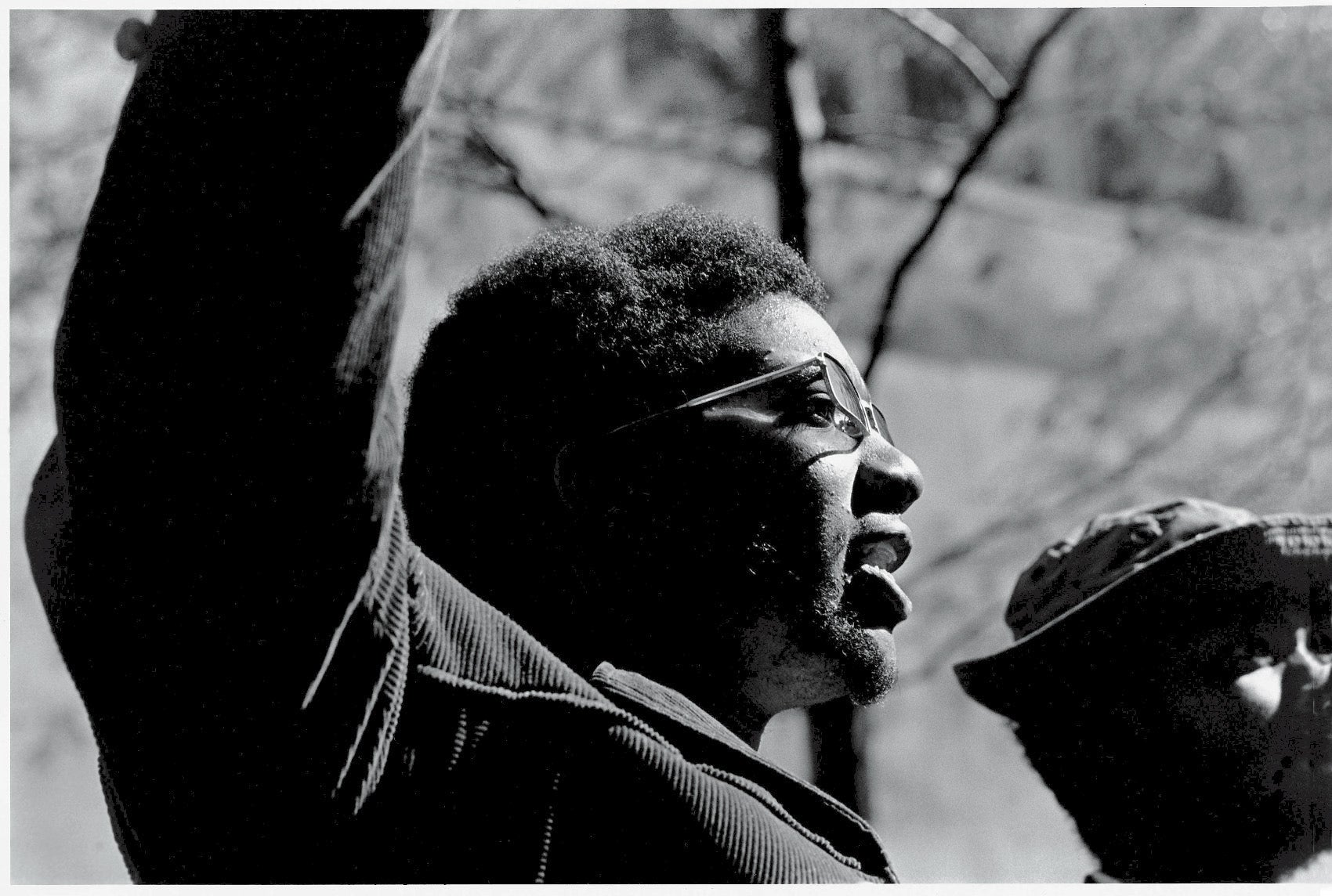

While Hampton Jr. was born into the fight for Black liberation, his father died from it. This month, 47 years ago, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Illinois State Attorney’s Office, and the Chicago Police Department succeeded in their mission to kill Fred Hampton. A rising star in the Black Panther Party, Hampton’s charismatic leadership and calls for economic justice and revolution across racial lines made him the target of a state-sponsored assassination.

By 1969, Fred Hampton had stepped up in the Party’s leadership while Huey Newton, the Party’s co-founder, was imprisoned. The ‘Free Huey’ campaign was galvanizing activists around the globe. Martin Luther King’s assassination a year prior devastated Black Americans and helped radicalize an increasingly militant message against capitalism and racism.

It was this growing popular resentment against economic inequality — and black leaders like King and Hampton that could effectively organize the masses to fight this inequality — that frightened government officials at every level. And Fred Hampton was a brilliant organizer.

Hampton was the son of Louisiana parents who joined hundreds of thousands of other southern blacks in the Great Migration to find a better life up north.

They found this new home outside of Chicago. While the economic opportunities were greater, the racism was no less detrimental. But a young Hampton battled through it. He increased the membership of his local Junior NAACP chapter from seven to 300 members in seven and a half months. This caught the eyes of the FBI, who consequently opened a file against him.

He was 14 years old.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter for the latest in hair, beauty, style and celebrity news.

Over the phone, through a southern drawl unearthing his Louisiana roots, Fred Hampton’s son sounds just as in awe of his father’s organizing prowess as other activists likely were in the 1960s. Hampton met his minimum goals to feed at least 3500 children a week in the Illinois chapter of the Party’s free breakfast program. When government agents attempted to pit the Blackstone Rangers against the Party, Hampton won the Rangers over. When competing gangs threatened to harm Black communities, and themselves, Hampton got them to agree to peace. For years, government officials threw everything they could at the prodigy to end his fervor and undermine the Party. Finally, when Hampton was just 21 years old, the Cook County State Attorney, the FBI, and the local police succeeded.

In 1969, still within the first year of his presidency, Richard Nixon flew over the Party’s headquarters in Chicago. According to Hampton Jr., Nixon was heard saying that the Panthers “got the last one, we’ll get the next one.”

The former President was referring to the killing of two Chicago police officers, which was blamed on Black Panther Party leadership despite evidence to the contrary. Nixon’s campaign rhetoric to return America to law and order got him elected to the White House. And with J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI’s Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO), they made the Panthers their primary target. Instead of a war against racism or poverty, America was embroiled in a war on Black activism.

Fears of Black people — which is most visibly concentrated in sporadic, individual interactions between white vigilantes, cops, and Black victims today — were institutionalized on the highest of federal levels. This was not lost on other civil rights leaders and elected officials. Though the depth of the federal government’s role in killing Fred Hampton wasn’t fully known at the time, civil rights activists and Black elected officials knew something was amiss.

Even mainstream Black groups, including the Congress for Racial Equality, SCLC, NAACP, and Urban League joined in protests against what they saw as a “calculated design of genocide” against Panther activists. As Julian Bond, a member of the Georgia state legislature, charged in the 1960s, “[t]he Black Panthers are being decimated by political assassination arranged by the federal police apparatus.” FBI documents that were uncovered once they effectively destabilized the Panthers proved this was true.

The FBI planted an informant in Fred Hampton’s inner circle and enlisted the local police to raid his apartment.

William O’Neal — a Black man who became the Minister of Defense for the Black Panther Party Chicago Chapter and Hampton’s bodyguard — was responsible for protecting Hampton’s life. O’Neal was also obligated by the FBI as their informant to help them end it.

O’Neal provided the federal task force with the floor plan of Hampton’s apartment. On December 4, 1969, the Chicago police shot nearly 100 bullets into Hampton’s apartment, all of which were aimed at the bedroom Hampton shared with his fiancée, Akua Njeri. Only one bullet was fired out of the apartment by any Panther.

I asked Fred Hampton, Jr. what he knows of that night. He has undoubtedly shared this story countless times and has heard his mother and other survivors recalling the horrific details of that fatal shoot-in. As police officers began firing, other Panthers who convened at their home for Party business shouted to officers that there was a pregnant woman in the room. Akua was about nine months pregnant with Hampton Jr., her only child. In an act of complete sacrifice, Akua covered her fiancée with her body as bullets ricocheted against their mattress. Through all the commotion, Hampton Sr. barely reacted. She knew something wasn’t right. O’Neal had drugged Hampton with Seconal, a sedative that left him immobilized.

Despite the hail of bullets, Akua, Fred, and many members survived the initial firestorm. In an interview with Democratic Underground, Akua recalls that two police officers entered their bedroom. “Is he dead yet?” one asked. When the officers realized Fred was still alive, they executed him at point blank range. Two bullets to the head. The other officer responded, “well he’s good and dead now.” James “Gloves” Davis — a Black officer notorious for brutalizing his own people– delivered the final, fatal blow.

Fred Hampton Jr., born Alfred Johnson, can’t recall precisely when he learned about his father and Black liberation.

“It was a way of life,” he told me.

That life didn’t come without sacrifice.

“It’s been some lows. We had to witness people who benefitted, who got jobs and careers. [My mom] got fired from jobs because of who she is. But I watched her principles.”

Hampton Jr. continues, “I was about 12 years old, and a book proposal [about my father] was brought to us. It was a cold, Chicago winter. Our gas was cut off. The proposal was making like the police was the protagonist. It was a story about building him up. I distinctly remember telling her, if we do this, our gas will come on. She said ‘we’re not going with it.’ She refused to compromise the legacy of Chairman Fred Hampton, of the Black Panther Party.”

Around the same time, Akua legally changed her son’s name to Fred Hampton Jr. Despite the negative attention his name brought him in Chicago’s still-racist criminal justice system, neither Akua nor Hampton Jr. have shied from his father’s legacy. After cops were acquitted for brutally attacking Rodney King, many Black neighborhoods around the country rebelled.

Hampton Jr. was charged with arson, even though Korean merchants whose shop Hampton Jr. was alleged to have burned questioned if the arson even happened. The line of questioning during the trial didn’t relate to the case. Instead, they focused on his political beliefs.

The junior Hampton recalls potential jurors telling the judge “his name is Fred Hampton, it’s Fred Hampton’s son, let’s just convict him.” He was sentenced to 18 years of prison. While in prison, where he served nearly nine of his 18 years, there were assassination attempts on his life. The prison tower displayed a picture with his face on it so he could be easily recognized.

Though the Hamptons have loved their people and continue to fight for Black lives, they haven’t been consistently loved back. “We paid the price for it. We’ve been shunned by a lot of people.”

It’s frightening to think about a reality in which government officials have unbridled power to conspire to kill you. In 2016, we are confronted with an America apathetic to Black pain and Black death. Of a racism that’s mutated and no longer has the power of a legalized Jim Crow caste system but that nevertheless functions, in practice, like the force of law.

But few people today can remember a time when America instituted the sort of brutal racism that could operate more bluntly instead of through the surgical precision of covert racism. Government leaders, from the local level up to the president, could identify any Black activist working to make America the place it always said that it was —o f freedom and democracy and equality — and viciously, illegally, and without consequence kill them, and the American dream along with it. Hampton Jr.’s oral history provides the jarring reminder that America, with all its claims of being great, never once lived up to it.

When I ask him how he feels about the apparent lack of social progress since his father’s death in the 1960s, he snaps me back to reality. For a man who experienced significant trauma, Fred Hampton Jr. is one of the most optimistic people I’d ever encountered. Though it appears like Black people in America experience a tortured cycle of pain and triumph with no true progress, the 47-year-old reminds me that Black Americans are actually on an upward spiral. We endure similar circumstances as our ancestors, with similar solutions and similar results. But the experiences are not identical. However slight the arc may seem, we are indeed bending towards justice.

Fred Hampton Jr. and Akua continue to chisel away and shape this arc, despite the fractures they have endured and the opportunities they have lost in the process. By the time Fred takes my phone call, he has just finished his “Free Em All Radio” program, which he hosts every Wednesday with Lady of Rage, the rapper best known for her 90s hit “Afro Puffs.” While in prison, he started the Prisoners of Conscience Committee/ Black Panther Party Cubs, which produces the radio show and provides its members with a platform to discuss politics with invited guests, current events, and their community organizing.

Hampton Jr. was also fresh from a trip at Standing Rock, narrowly escaping the freeze, where he was battling in solidarity with indigenous communities protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline. To honor her ex-fiancée and introduce new generations to his life and the Black Panther Party, Akua regularly provides tours of the apartment where Fred was slain for International Revolutionary Day, which they celebrate every December 4th to honor Fred Hampton’s life and organize around contemporary issues.

During one of his radio programs in late October, Fred Jr. raps an interlude before continuing with the show. His closing line sums up his life’s work:

Long live the legacy of the Black Panther Party, protect and respect it, and never, never neglect it.