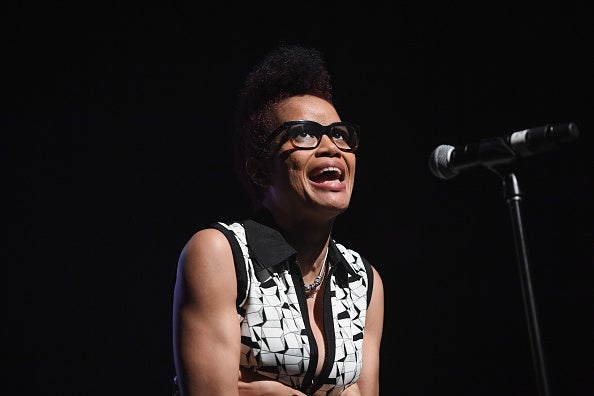

To watch Staceyann Chin perform is an experience.

It’s not just the biting truths she speaks from the depths of her soul. It’s how her tone changes from a slight gruff voice to an orotund sound that takes hold of your senses and commands your attention.

Chin has been outspoken since she made her surprise debut from her mother’s womb and landed at her grandmother’s home in Jamaica. Overcoming a tough childhood in Jamaica, she migrated to New York City in the 90s. She began performing as a poet and political activist in 1998. From Russell Simmons Def Poetry Jam to Broadway, Chin’s poetry has astounded audiences across the world with stories from her upbringing fused with political commentary.

And that’s what makes her special. Chin’s ability to weave politics with identity struggles, racism with gender and sexuality with patriarchy is intersectionality at its best.

She lives in it.

ESSENCE recently sat down with the activist-poet to talk everything from her writing process to the Trump administration and raising a young daughter on her own in an increasingly gentrified New York City.

Your performances are always so filled with passion and political commentary. What is your process of creating these performances?

I’m informed by a lot of what’s happening in popular culture, like the relationship between us and the power that decides what kind of lives we live, the political structures, the structures about law and order, the justice system, the police and the school system. Whatever is happening culturally, politically, racially in my lived experience becomes a thing that I write about. If things didn’t happen to me or didn’t happen around me, I don’t think I would be able to write. I’m not the poet who is moved by nature, like the trees and the plants and the river. Unless the river is polluted and people are drinking the water and they’re immigrants or people.

New York City has been your home for nearly 20 years. What does the new landscape of the city feel like?

New York used to be a place that was so diverse and so mixed. New York 20 years ago was a place that was so full of a lot of energy and a mix of a lot of different kinds of people. In different neighborhoods you would find enclaves of people of color, but with other different kinds of people of color with White people peppered in. But now I feel as if everybody of color is being pushed out. I’m watching my building change, my neighborhood change.

I am being squeezed tightly and I am hanging on by my fingernails in New York. But we have to take on this spirit of Malcolm X, Sojourner Truth, Audre Lorde and the spirit of these activists and take back these urban cities that we’ve built from brick to asphalt to window to roof. We built these cities and now we’re being pushed out of them. We owe it to the bodies that built these cities to stay and fight.

How has your work changed since the election of Donald Trump?

Trump is not a new invention in America. But Trump is a new acceptance of this thing we thought we had at least taken out of the vocalized articulated identity of America. The Trumpian characters that we see or we have reason to navigate in this new century have been historical. We see him in 12 Years a Slave. We see him in movies like Roots. We see them in movies of a time long gone. We hear them wearing uniforms or preventing people to vote during the Jim Crow years.

He is not a new thing.

He is as old as America itself. What’s happened is that we thought we had evolved pass this moment. As a woman, I thought we had evolved pass a moment where a man who publicly been heard advocating for the sexual harassment of women in the most crass of language to be immediately soon after elected to the highest office of the land.

You’re raising a very confident and precocious five-old, Zuri. You’ve also written about being abandoned by your mother. What is it like for you teaching your daughter to navigate the world and also growing through your experiences as a mother?

I never got to experience a mother/daughter relationship as a daughter so I’m experiencing it as a mother. I have no idea what it feels like on that side. The single, most amazing part of being the mother of a kid who’s allowed to push back is how much compassion you have for the people who you thought were people who didn’t allow you to push back.

It’s so much easier to raise a drone or to raise a kid who’s like ‘why should I do that?’ and the parent says ‘Because I said so.’ It’s so much easier to raise a kid without having them ask questions. It’s easier to raise a kid that’s afraid of you. But when you’ve committed to speaking truth to your child that means that you can’t lie about stuff like ‘what’s cancer?’ The greatest tragedy and the greatest joy of parenting is you can’t protect your kid but that they might be able to protect themselves.