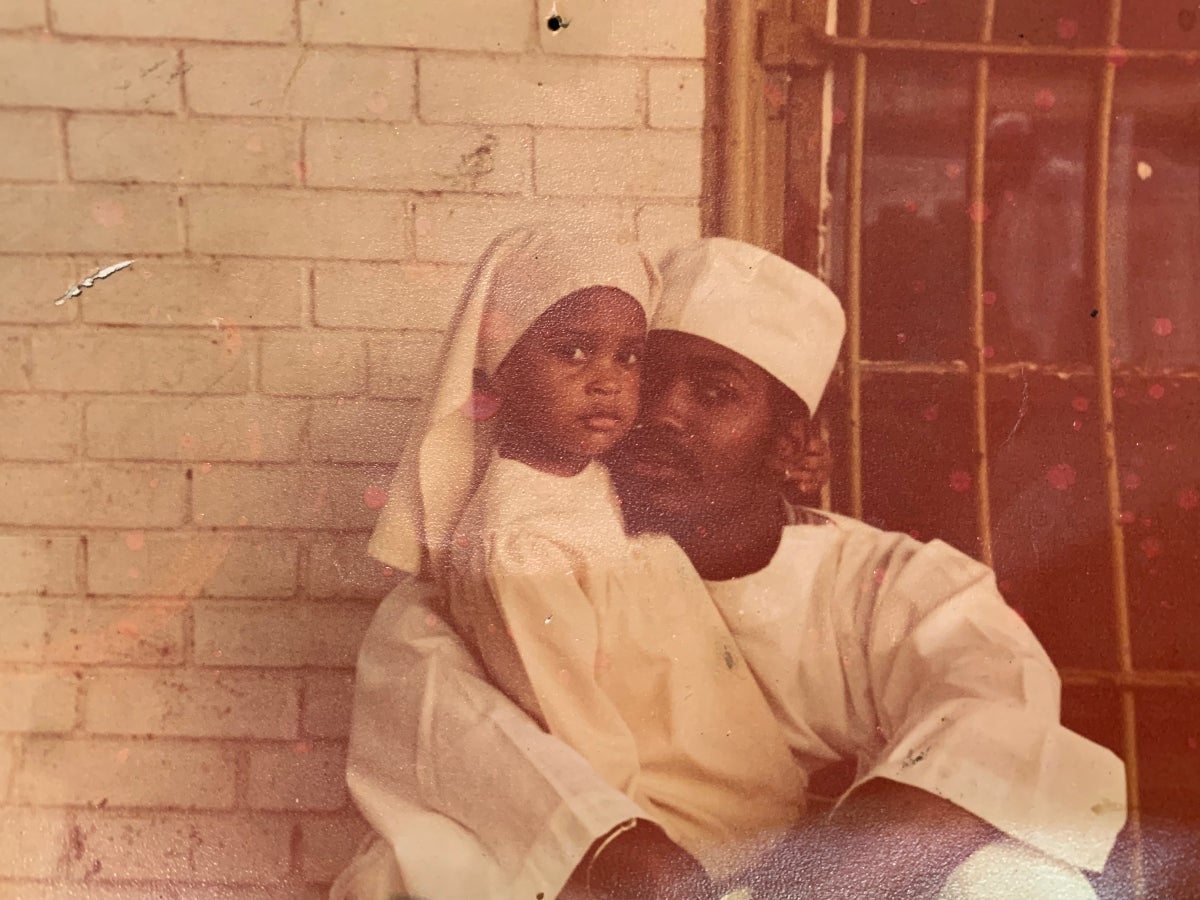

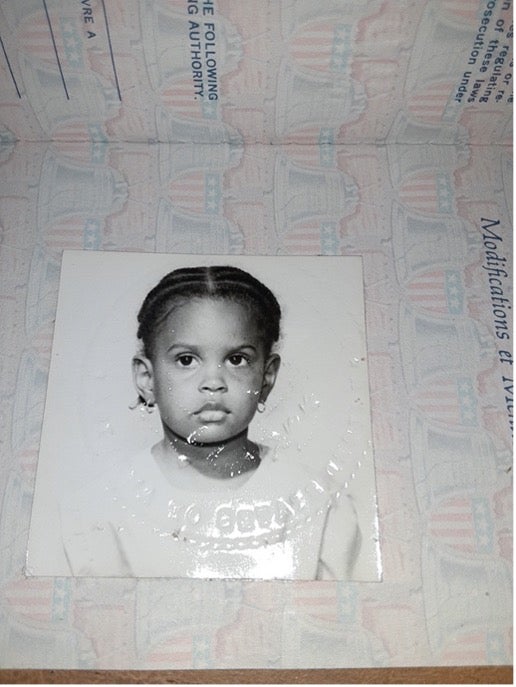

When writer N. Jamiyla Chisholm was two years old, her family joined a religious cult led by a man who called himself Imam Isa. Suddenly called by a new name, separated from her parents and forced to sleep on the floor with dozens of other girls each night, she learned Arabic and wondered why her mother didn’t protect her from abuse.

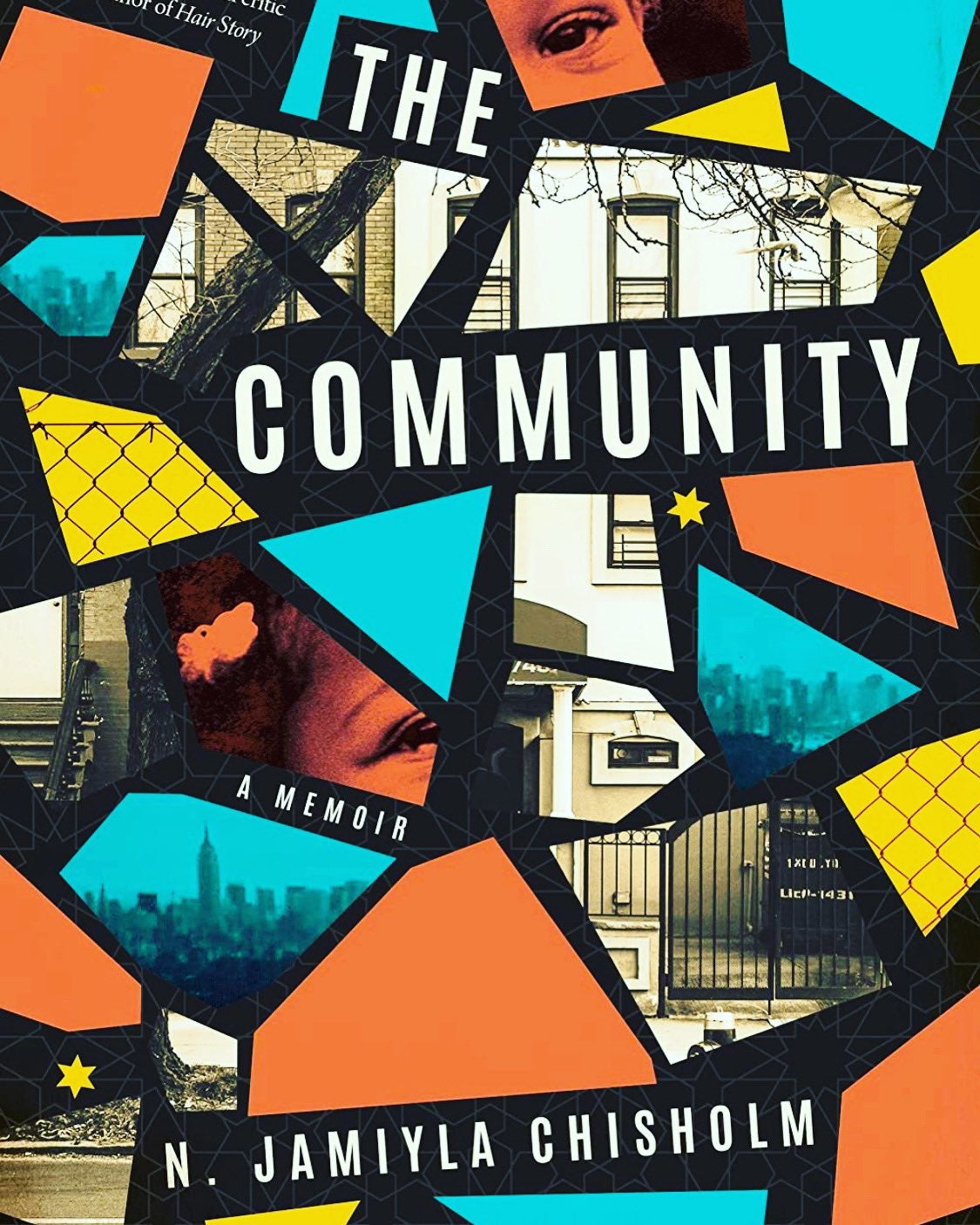

Decades later, now using the name Dwight York, their leader was sentenced to 135 years in prison for child molestation. In her memoir The Community (Little A, $24.95), Chisholm writes about her experience in the Ansaaru Allah Community, breaking open her memories and lying them alongside the events both historical and contemporary that drew people to York’s Black separatist ideology. The result is a thoughtful meditation on the things that hold us together—and the things that pull us apart. Here, we talk to Chisholm about the challenges of memoir, the importance of perspective and the beauty of Blackness.

More than a chronicle of life in the Community, your book also serves as an unfailingly honest documentation of your relationship with your mother. How did writing it impact the way you all relate?

In writing this book, learned how extremely elastic memory is. I interviewed my mother to examine the memories that felt fluid and make sure they weren’t the products of a child’s overactive imagination. That process confirmed what I remembered, but it also gave me an opportunity to see the experience from her perspective. I realized that I’d seen her as a villain in my story. She took me into that house and then walked away, and none of it made sense to me until then. I started to see her as a whole person, not just a mother living for me or my brother, but a woman who had her own dreams and her own failures who did the best that she could with the tools that she had. I also realized that I could not tell my story without telling hers. They are inextricably intertwined. There was no way for me to understand what happened to me without understanding what happened to her.

You write that the Community gave your parents pride and a connection to a collective future that was bigger than them. What did it give you?

Eventually it gave me that same level of pride. Even as a child, when the Community was not a very good space for me, it made me feel special. I don’t know if I could have been around so many beautiful Black people without being proud. I’m very clear that the survivors were trying to create magic, to make something out of nothing. For all the Community’s faults, that was beautiful.

You lay bare so much of your life on the pages of this memoir. How are you grappling with the realities of letting so many people in? What does that feel like right now?

Honestly, it feels bizarre, but I can’t turn back now! The moment I got serious about writing a memoir, I knew that I had to go all the way. I did a lot of workshopping when I was working on my MFA, and I often got feedback that I wasn’t telling the whole story, that readers did not understand how A, B and C turned into Z. I was holding back, doing some protective dance with my mom. I didn’t want to face the harder parts of my journey. But if I was going to do this for real, I had to show my panties, so to speak. I hope my candidness and honesty are nurturing and helpful to readers.

You write of your mother, “She lost two years of my life to that house because she didn’t know how to say no.” Talk to me about what you’ve learned about saying no.

I’m like a two-year-old. No is one of my favorite words. No is a boundary setter, it helps me create space for myself, it helps me stand up for myself, it puts people on notice that not everything is up for consideration. If my mom had told my father or any of those people in the Community “no” early on, we wouldn’t have lasted more than a week in that place, because they would’ve kicked us out. The Community was a place of yes. That’s how you survived. That’s how others were able to accumulate power—people just kept saying yes. I’ve learned that sometimes you need to say no and walk away for your own faith keeping.

What was the most surprising thing you discovered while writing this book?

The most surprising thing was how hard it is to write about something you think you know well: myself, my family, my memories. I thought I knew me. I thought I knew us. But I learned so much about my parents and their relationship, and I learned that my mom was a heck of a lot stronger than I had given her a credit for.

If this book had a soundtrack, what would be on it?

Everything Nina Simone! All the freedom, all the femininity, all the anger that she sang about, I feel like that’s what I’m trying to explore. She didn’t mince her feelings. I hope that I was able to be as honest with this book as she was with her music.

What have you read and loved recently?

I have to admit that I have not been reading a lot during through this book process. But a book that I always recommend is bell hooks’ memoir, Bone Black. I love, love, love it and I recommend it to every Black girl everywhere. She is just so unflinching in her memory of being a little Black girl growing up and all the joy that she experienced in finding herself. It’s really beautiful.

When readers finish the last page of The Community, what do you want them to walk away with?

First, that bad shit can happen to any of us. Nobody is immune. For those who grew up without a parent, I hope they leave knowing that they are not alone and they are not lost, because they can always find themselves. And I want them to know that the stories that we believe about ourselves aren’t always true, and uncovering our real stories and our real selves is self-love.