We often forget that Civil Rights heroes are real people. We read about their brave acts, but they remain two-dimensional, stuck inside the pages of our history books. But our heroes had families. They had sons and daughters who often witnessed the violence and trauma inflicted on their parents in the fight for freedom.

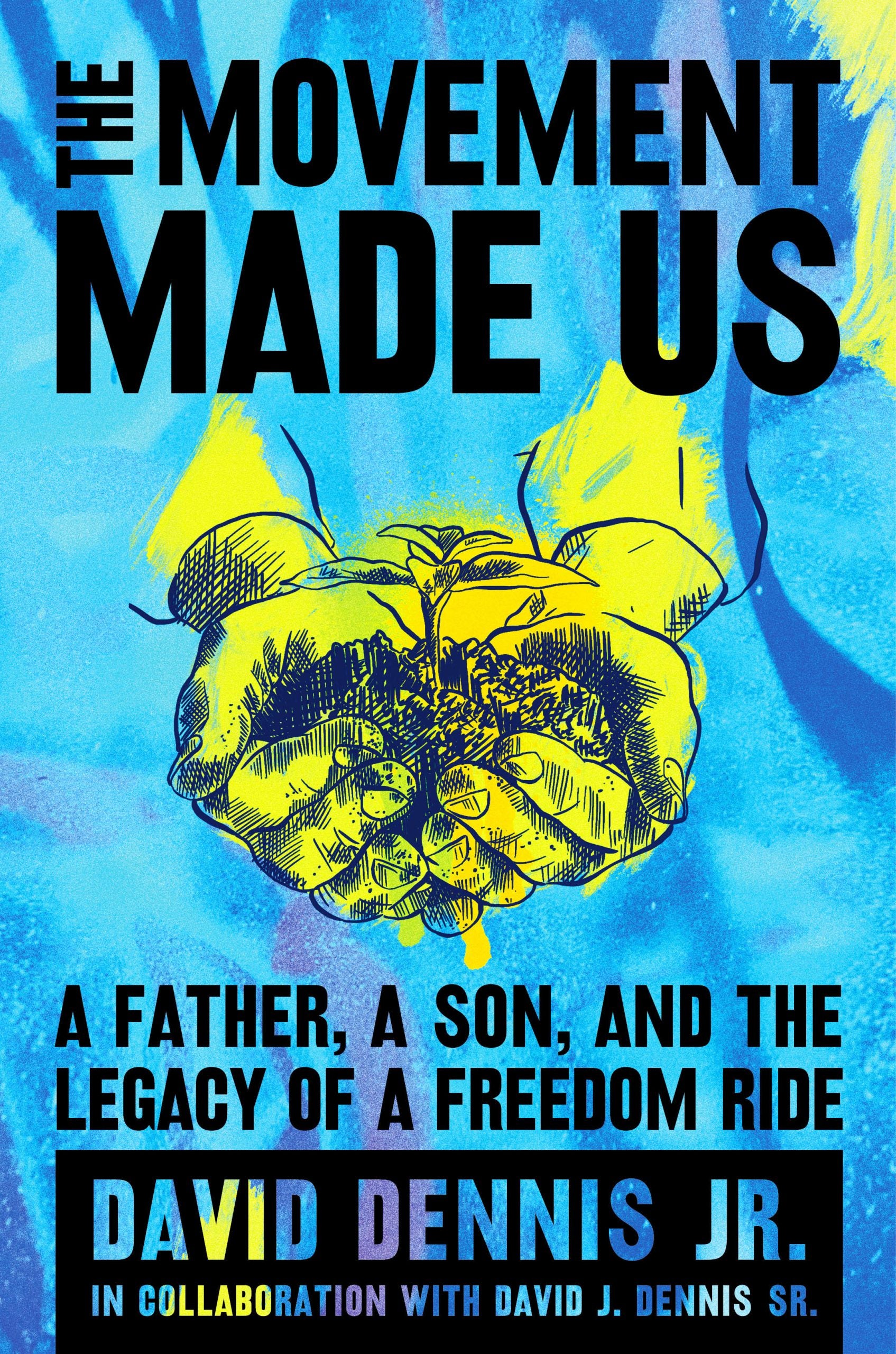

One of those sons is David Dennis Jr., who recently wrote, The Movement Made Us: A Father, A Son, and the Legacy of a Freedom Ride which chronicles his father’s involvement in the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. David Dennis Sr. joined CORE (Congress of Racial Equality) in 1960 and went on to organize lunch sit-ins, Freedom Rides, and voter registration drives. He was also beaten and jailed and witnessed the brutal deaths of some of his closest friends and fellow freedom fighters.

In the moving memoir, Dennis Jr. alternates between his point of view and his father’s point of view, piecing together stories from his father’s time on the front lines. Throughout the book, readers learn about the sacrifices made by Civil Rights activists and the trauma that Black families had to endure in the fight for freedom.

Dennis Jr. recently sat down with ESSENCE to talk about writing the book, what he learned about his dad in the process, and how the book has helped heal his relationship with his father.

This is such an important story to tell. Why was now a good time to write this book?

DAVID DENNIS JR. – The logistical answer is that my dad is 81 years old now, and I was really thinking about the time we had and I wanted to get these stories done as quickly as possible. Also, there was the fact that a lot of this book was written when Donald Trump was president and a ton of it was written after the George Floyd summer, and it just felt like we needed some sort of reminder of what regular folks were able to accomplish and what can be done if we just do something. I think we found a way to make a book that wasn’t like a step-by-step guide to activism from a Civil Rights person but something that showed what’s possible, and I think that’s why it’s so timely.

As you were talking to your dad about his time on the front lines, what was something that surprised you that he had gone through or witnessed?

DENNIS JR. – When you hear these stories and these oral histories you don’t really know the timeline of everything. So I didn’t realize that the Harlem Riot [in 1964] happened right when [Civil Rights fighters] Goodman, Charter, and Schwerner were [shot to death] and missing. So much of this stuff was happening over the course of a few days or a couple of weeks. There was really no downtime and it was just a constant barrage of really intense moments. Those are some of the things I learned – just how constant the action and all of the trauma and violence were happening during this time.

How has your relationship with your dad changed since writing the book?

DENNIS JR. – My dad and I were in a good place for us to be able to write the book, but we were sort of in an unspoken good place that a lot of parents and children get to where they’re just sort of fine, but they didn’t really talk about how they got there. So this book caused us to have those conversations that put us in a much better place that I didn’t even really know existed. We just finished the book tour and we’re traveling together, hanging out, and doing all kinds of stuff, and we don’t have anything that’s unspoken between us.

You write about being angry with the world and what the movement took from you and your father. How did you come to terms with your anger?

DENNIS JR. – Sometimes I still feel angry. Not necessarily for my dad and me, but for other people. For the families that could not have this experience my dad and I just had. I’m angry that Medgar Evers does not have the time to do this with his children. Or Herbert Lee or James Chaney who had a daughter who was born a few days before he was killed. They don’t have the opportunity that me and my dad had and that’s really frustrating.

But I’ve also seen there are a lot of healing qualities of this book. People have reached out and talked about how it’s been so good for them to have this. I think that sometimes when you can heal your relationships and have better relationships with your children, it can repair things that have been lost in the past.

People who write memoirs, especially those that are deeply emotional or traumatic, often need breaks. Did you feel like you had to take breaks or step away from the book at times?

DENNIS JR. – It was more so micro-breaks. I would try to sort of buffer me and dad’s time together with some self-care. We’d hang out and I’d ask him some tough questions, and then I made sure we did something at night that was fun. I was mostly concerned with him, making sure that he got breaks, and making sure that I wasn’t pushing too hard. For myself, I’d take breaks in between book drafts. When the publisher had the book I would try to not think about it at all so I could come back to it feeling as well as possible. But my main concern was that my dad was okay.

Do you and your father talk about the Black Lives Matter Civil Rights movement today? What does he think of the movement?

DENNIS JR. – He sees a lot of hope in it. One of the good things is that he feels that people are doing something, which is extremely important. He’s happy that folks are organizing, and he’s happy that people are trying to follow those traditions of learning from the local communities.

What’s one thing you want readers to take from this book?

DENNIS JR. – I want people to feel as though they can do something. I want them to know that you don’t have to be Martin Luther King Jr. or Medgar Evers. You don’t have to die to be considered somebody who did something. And I want people to be empowered to say, “If I go and do one thing, then I’m doing something positive.” If everybody has the mentality of “let me do something to get us free or get folks like us free” then I think that’ll turn into everyone doing something. I also hope you see that these are real people. These aren’t flawless heroes. These are real people who are just trying to do something. And if you try and do something we can go a long way.