For Nikole Hannah-Jones, a journalist who has won nearly every award, accolade and honor that her professional industry has to offer, there is yet more to pursue.

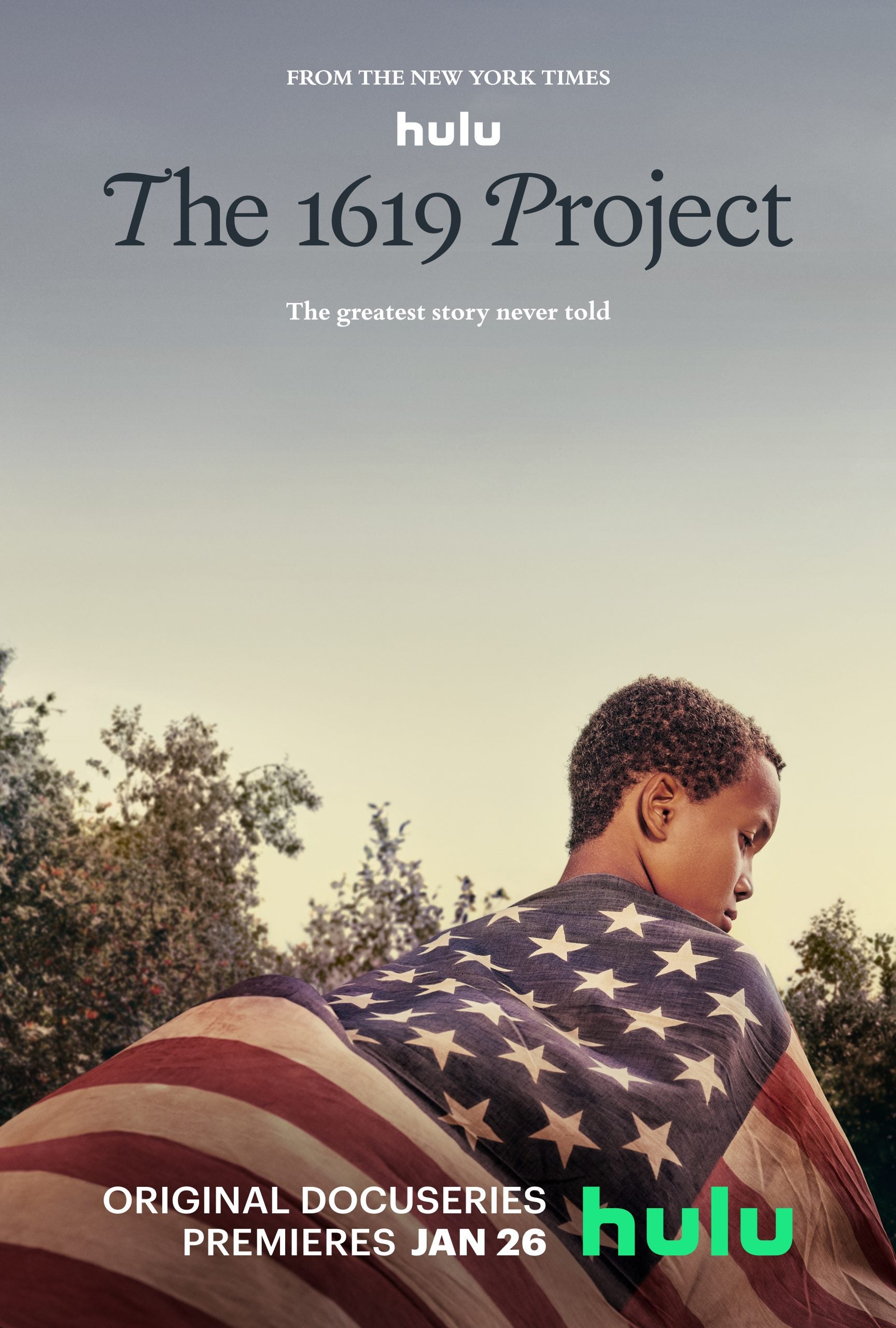

The New York Times Magazine writer who conceived of “The 1619 Project”—and won a Pulitzer Prize for her contributions—is a journalistic virtuoso, but admits that she is less versed in translating the written word onto the big screen. Until now, that is. On January 26, “The 1619 Project”—an endeavor which drew the ire of politicians (including a sitting president), legislators and the right-winged media—will take on a new form as a docuseries.

“The 1619 Project”—a six-part video collection airing on Hulu—features hour-long episodes adapted from the original New York Times articles, building upon several themes: “Democracy,” “Race,” “Music,” “Capitalism,” “Fear” and “Justice.” Oscar and Emmy award-winning director Roger Ross Williams and Peabody-winning executive producer Shoshana Guy, step-in as the series director and showrunner, respectively.

I spoke with Hannah-Jones, Williams and Guy during a virtual interview, on a sunny Saturday afternoon. The mutual respect and admiration that they shared was palpable. There was a sense of fluidity and ease amongst the all-Black trio. They spoke the same ‘language,’ picked-up on the same references and laughed at the same jokes. Though I wasn’t physically present, their room felt warm and joyous. Together the storytellers so masterfully reimagined this oft untold account of America—one that centers the consequences of slavery and the contributions of enslaved people.

“The 1619 Project” docuseries is absolutely riveting.

Perhaps what is so immediately engaging is a departure from the original collection—Hannah-Jones is present in every single episode and becomes personal. In her interviews, the investigative reporter is commanding and charismatic. She’s even-keeled but allows herself to feel emotion; at moments, even crying, becoming vulnerable in ways that she hadn’t expected. Not only does Hannah-Jones shepherd audiences throughout the series—shod in pristine Air Jordans with her pen and notebook in hand—but the Waterloo, Iowa-native brings with her the spirit and the memory of her kin; the very people who built this nation.

“I come from humble folks, these are the people who made America.” Hannah-Jones tells ESSENCE.” It’s not famous people. It’s not rich people. It’s regular people and particularly people who descend from American slavery, who built the wealth of this country, who fought for democracy, for this country, and to be able to tell that story both largely and also very intimately through my family and to be able to put Waterloo, Iowa, on the map is so important to me.”

Indeed, the docuseries begins in Waterloo, but Nikole Hannah-Jones walks with her ancestors through various American cities, rightfully weaving them into the fabric of this nation.

First, “Democracy” transports audiences to Nikole Hannah-Jones’s childhood home in Iowa. There we are introduced to her dad, Milton Hannah—a Black man who was born on a sharecropping farm in Mississippi—and learns of his connection with the American flag. “Race” presents Hannah-Jones’s maternal family, who are white. In the opening sequence, her maternal grandfather (a white man) is juxtaposed with the journalist’s paternal grandmother (a Black woman), the matriarch of the Hannah family who is referred to as “Grandmama.” Both grandparents were born in 1924, but because of their race and sex led disparate lives.

“Music” is particularly nostalgic. In this chapter, we learn more about Milton Hannah and his favorite group, The Temptations. “Capitalism” becomes emotional as Hannah-Jones (and her cousin) so tenderly honor her favorite uncle, Uncle Eddie. “Fear” shares a short anecdote about Hannah-Jones’s great Uncle Milton who was chased out of a white neighborhood in Mississippi, only narrowly escaping death by jumping into the Tallahatchie River—the same river where Emmett Till’s mutilated body was disposed of. Finally, “Justice” incorporates Percy Paul—Hannah-Jones’s great grandfather who owned a Black cab company in Mississippi, and later brings back Grandmama, who left all that she knew in Mississippi and moved to Waterloo for the promise of a better life. There, with the help of one of her sons, Grandmama became a homeowner.

It is important to acknowledge that these chronologies are notes throughout the series—threads which draw the audience closer to Hannah-Jones. They do not overshadow the larger themes, rather they are subplots, which punctuate the vast concepts that are explored in “The 1619 Project.” These intimate stories add texture to the series. Still, in many ways, this is an homage to the people, who for Hannah-Jones, are greatly significant.

“My family means everything to me. They’re the reason why I do the work that I do. They’re the reason why I see the world in the way that I do. Why I understand race the way that I do,” says Hannah-Jones, who is also an executive producer of the docuseries. As it pertains to race, specifically, there was no ambiguity about who she is or how the world would perceive her. Decades ago, the late Milton Hannah sat his three daughters down, and let them know that despite their mother being white, they were Black, just like him.

“Her family is America,” Director Roger Ross Williams says, explaining how Hannah-Jones’s kinsfolk became a part of the series’s editorial vision. “Her family lives in middle America, but they also show the real America. And that was so important to show to the viewers and so important to have her as a guide.”

In addition to Hannah-Jones, and her loved ones, serving as a conduit for the American story, it was striking to see how culturally “The 1619 Project ” felt so unequivocally Black. Despite interrogating very dense topics, the documentary series found space to infuse cultural touchpoints that are endemic to Blackness. The accents feel authentic—in the first three minutes of the “Capitalism” chapter, alone, these moments were plenteous: Take, for example, Gill Scott-Heron’s “Whitey on The Moon,” spliced with Martin Luther King Jr.’s “The Three Evils” speech. Mobb Deep’s “Survival of the Fittest,” faded into an instrumental of Kendrick Lamar’s “Money Trees.” Or even the recreation of Gordon Parks’s famed 1942 photo, “American Gothic,” among other moments.

“Look at who made this documentary series, that is why it feels so authentically Black,” says Hannah-Jones. “The 1619 Project” is a collaborative effort, produced by Lionsgate’s One Story Up Productions (which is owned by Ross Williams), Harpo Films and The New York Times. For the curious, the predominantly Black crew didn’t play spades during production breaks, rather their game of choice was the dozens. “We liberated them, like bring your Black self… If we don’t have this crew, we don’t have that [Black] feeling, period.”

Adds Guy of the feeling on set, “It’s such an opportunity to be able to work with Black people and be with Black people and create with Black people.”

Perhaps the ‘Blackest’ aspect of the entire docuseries is the personification of a supremely courageous and undeterred spirit, as seen through the various characters in “The 1619 Project.” This is the same spirit embodied by our ancestors—the men and women who were shackled and shipped, as cargo, across the Atlantic Ocean; toiled and tortured on plantations; built the major cities; endured Jim Crow.

For centuries Black people have maintained an unwavering determination to fight against injustice, in the spirit of our forebears. Hannah-Jones believes that Black people will always be fighting to dismantle the legacy created by chattel slavery.

“We didn’t have justice then. We don’t have justice now,” she says. “What choice do we have, but to fight for the future that we want? And that’s the argument of the project. We’re not powerless. And Black people have never been powerless. We have fought and we will continue to fight.”