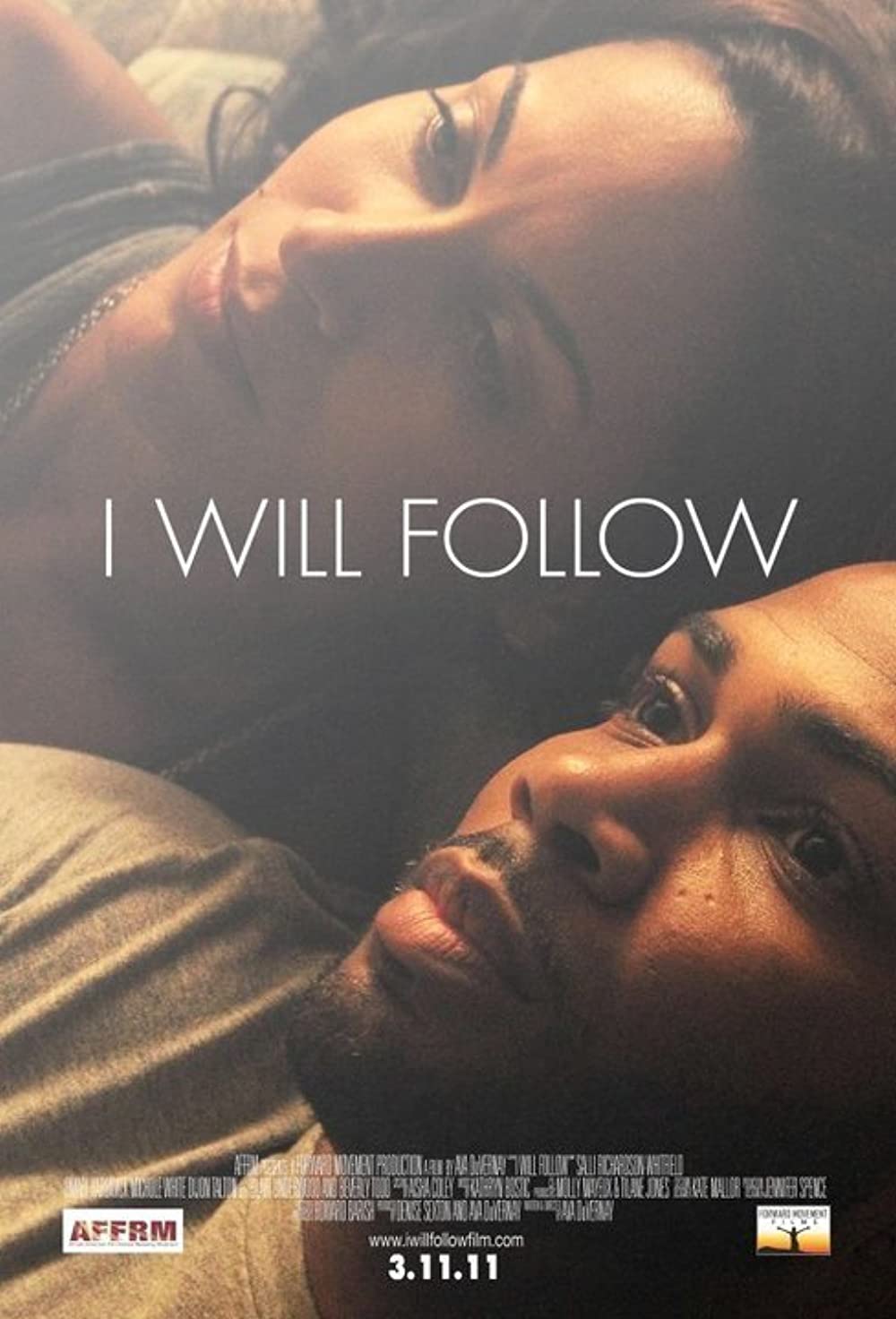

In 2011, a year after the release of her film I Will Follow, Ava DuVernay noticed that her low-budget independently made film was fighting an uphill battle. A battle her white counterparts didn’t have to fight. So she had an idea. She figured that if she could self-distribute her own project successfully, she could use the same model to do so for others.

“[I thought] what if I created a pipeline so it can be a collective distribution?” DuVernay told ESSENCE. “Why don’t we use the money from one film to go into the next person’s film? So all that we do for ARRAY is really built off of I Will Follow. All of those filmmakers–it’s almost 40 of them– each of them is living off the seed money from I Will Follow. And that money was made by Black people in top markets who went out to the one theater that was playing the film.”

The plan worked. Not only has ARRAY been able to produce and distribute around 40 films, Hollywood took notice of DuVernay’s work and tapped her to create larger feature projects as well. In 2018, the filmmaker and director made history as the first Black woman to direct a film with a budget over $100 million. Forbes recently named her one of the most powerful women in entertainment. It’s a superlative that DuVernay appreciates for the fact that it makes her mother proud.

“To see that pride in her eyes means a lot to me. And that’s probably where it begins and ends,” DuVernay said. “In Hollywood, as in a lot of different power structures, power’s really relative. Power for what? Power to portray images of Black people within a structure that I don’t control? Power to distribute films that no one else will distribute? Power to feel comfortable enough to say my piece in a room full of people who don’t value the power? What are we talking about? It’s an adornment. If it brings some inspiration to people, happiness to people then I will take it.”

While DuVernay recognizes the limits of her power in Hollywood, she does know that there has been progress.

“When you look at the shows with four Black women who are friends on air right now: Insecure, Sistas, Harlem, Run the World, Twenties. I remember when we just had Girlfriends and we were happy with that,” DuVernay says. “When we just had Living Single and we thought, ‘You know what? Thank you.’ Across the board, Black women are leading franchises, showrunning. We stand on the shoulders of Black women who did that 20 years ago. And I hope that they’re proud because [their work] is bearing fruit.”

Still, there are deep, systematic issues still thriving. While it might be easy to attribute all of it to malicious, intentional racism, DuVernay says unconscious bias is a real thing. She’s recognized it in herself.

“I’m working on a project right now with a woman named Lauren Ridloff. She’s a sista: Black and Latina. And she’s deaf,” DuVernay explains. “I have all kinds of bias that I’m not even conscious of when I talk to her. I’m putting my foot in mouth every fourth word because we’re talking about things that have to do with deaf and hearing culture and I am so uneducated.”

DuVernay offered up an example of hearing bias with an anecdote about cochlear implants.

“You know those cochlear implants they give kids so they can hear? I thought that was a good thing. But when I’m saying that, what I’m saying is, ‘That child is not whole if that child is not like me.’ The deaf parents don’t see anything wrong with the child. But the hearing parents do. That’s unconscious bias,” DuVernay said.

The filmmaker says being confronted with her own shortcomings and subsequent feelings reminds her of how others may feel when they’re speaking to people of a different ethnicity, race, culture, or gender.

“It takes a lifetime to walk a mile in someone else’s shoes,” DuVernay says. “So we could all admit that we have unconscious bias.”

In the years since DuVernay has found success in this industry, she’s been asked several times to give advice to aspiring filmmakers and storytellers. Consistently, she shares that people–particularly women– shouldn’t wait for permission to follow their dreams. It was that concept that fueled ARRAY.

[Ten years ago] with ARRAY, there was no one in the industry who wanted to talk to me,” DuVernay explained. “There was no one saying, ‘We want to listen. We want to disrupt.’ There was no Black Lives Mattering. There was no corporate responsibility or even an Instagram to put a black square on.”

Still in spite of the lack of access and exposure, DuVernay, along with two other women whom she credits for the company’s success, helped contribute to the shift in entertainment we’re seeing today.

“We built our own systems of production, distribution and marketing. The fact that a decade of disruption has brought us here… It was literally me, a woman named Tilane Jones–who is now the president of the ARRAY companies. And a sista named Mercedes Cooper,” DuVernay says. Cooper now serves as the VP, Public Programming.

“It was just the three of us. I get emotional when I think of those two because there’s no way I could have done anything that I’m doing now. There’s no way we could have accomplished what we have, dream the dreams and be able to live them coming true if it wasn’t for those two women by my side.”