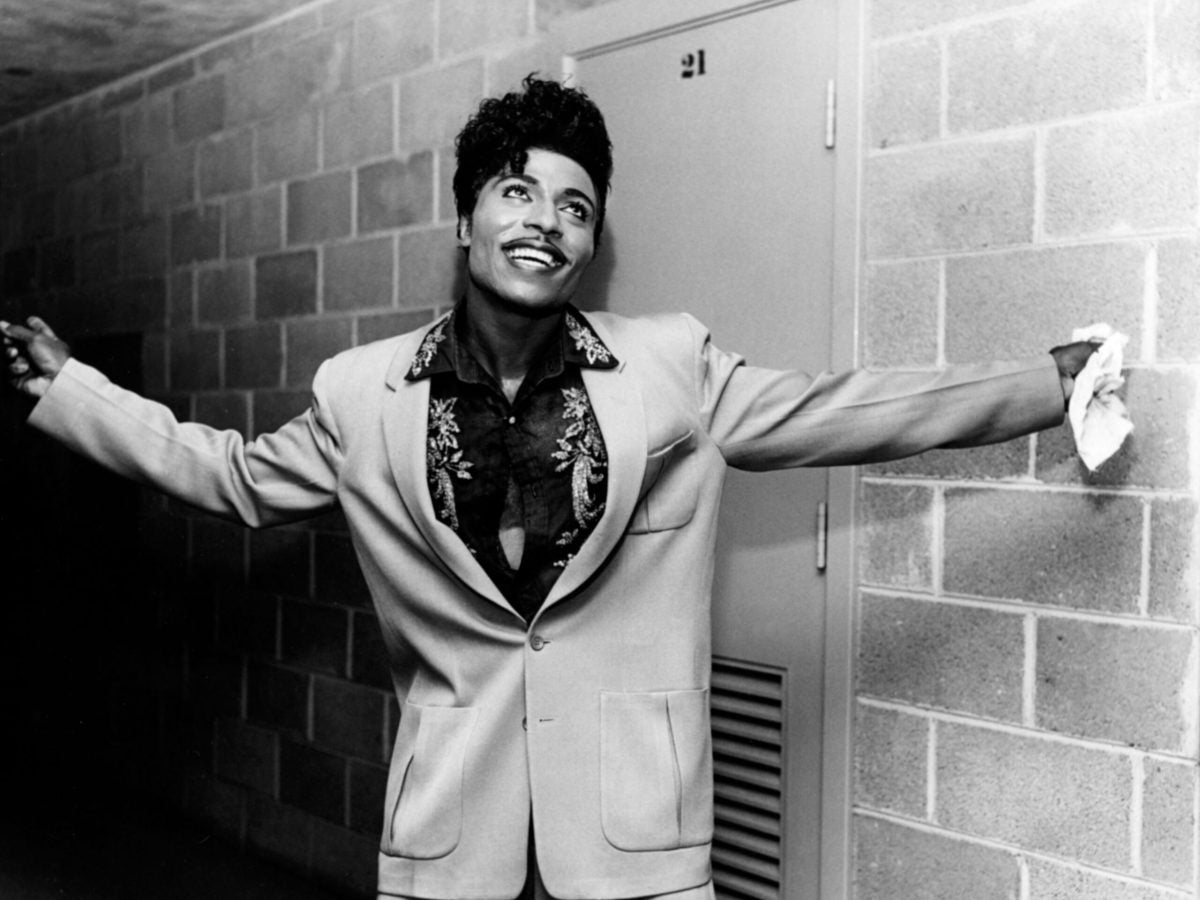

The word “fearless” perhaps best defines the late Little Richard. A pioneer of rock ‘n’ roll who broke the color barrier in the 1950s with hits like “Tutti Frutti” and “Long Tall Sally,” the Georgia native defined a genre and inspired generations by defying societal expectations. Now, he is the subject of the PBS special, American Masters – Little Richard: King and Queen of Rock ‘n’ Roll.

Premiering last Friday, this edition of American Masters provided an intimate exploration of the renowned, electrifying and multifaceted entertainer, and also features interviews with fellow musicians Keith Richards, Ringo Starr, Big Freedia, Nile Rodgers, Pat Boone, Ron Jones, and Deacon John; activist and drag performer Sir Lady Java; Little Richard’s spiritual advisor Reverend Bill Minson; producer H.B. Barnum; and historian Dr. Tyina Steptoe, among others.

Little Richard is widely recognized as one of the first crossover Black artists but spent years feeling his contributions to music have been overlooked in favor of white artists. His advocacy for the rights and recognition of Black artists was a lifelong project, and is a struggle that continues even in the wake of his passing over 3 years ago.

Friend and colleague of Little Richard – the Grammy Award-winning Bobby Rush – spoke with ESSENCE about the singer’s legacy, his artistry, and his long lasting impact on the music industry. “I thought he was a great piano player,” Rush says about his first meeting with Richard. “And he was the kind of guy I wish I could be – taking a chance in doing what you wanted to do regardless of what people said or thought about it.”

ESSENCE: Take us back to the first time you met Little Richard.

Bobby Rush: I believe it was 1955. Could have been 1956 when I first met him. He impressed me because during those times, as a black man, black people weren’t really able to speak out with what they wanted to do like Richard was. You know, because we couldn’t go to certain places because of the color of your skin. So that’s what impressed me the first time I met Richard. His energy was like, “I don’t give a shit what nobody says about me. I’m doing my music. I’m good at what I do. You accept me or you don’t.”

So what was your professional relationship like with Little Richard? How was it performing and recording with him?

Oh, well man, Little Richard was the kind of guy, whatever he did, he didn’t record it over and over and over. Whatever he did, he did it in one or two takes, and If that wasn’t right, hell with it, he was just that good at what he was doing. He has that kind of attitude, man. And that drew me closer to him where I wanted to be more like a Little Richard.

As I grew up in this life as a music man, I wanted to be a part of that. I want to be a part of that. And I relate to him like a Muddy Waters, or Howlin’ Wolf. Howlin’ Wolf was the same kind of a person, but he was a blues man who didn’t take no jive off of nothing or nobody. And Richard was the same kind of person. He may seem to take a back seat at the moment, but when he got on the stage, whatever he would take his back seats, he threw wonder. He may have made an agreement to do something with management, with club owners or with festivals, but when he got on the stage, Little Richard did what the hell he wanted to do on that stage for that moment.

Knowing him the way that you did, how do you feel about Little Richard’s legacy?

Whatever he did, he thought that was right. He didn’t compromise with it. And if it wasn’t Richard’s way, it was no way. He was true to his craft. He brought a lot to the table. And I didn’t realize when he was complaining so much about what he’d get his just dues until finally he did, being the king of rock and roll, I understand him now. Because after almost 90 years old myself, I can understand. I’m a leader. Richard was a leader, and he was the best at his game. Because the white boys took all of his ideas and direction because they were white, and made 50 times more money than he would ever make as a black man.

That bothered Richard – and it bothered me too, once I found out what they were really doing to him, not only just to him, it’s to the race of black men and women, period.

How much do you think that affected him in the long term, if at all?

He said that he’d been used and misused and abused because of his music. He didn’t make the kind of money he wanted to make, and he didn’t get the credit for doing what he was doing as a rock and roll artist . I believe that he was bitter about that on his dying bed. And I’m telling you today, I have tears in my eyes talking about a man who meant so well by his music. He meant so much about the people who loved him and his music, but he didn’t get all the credit that he’s due for what he did.

I’m this black man. I’m his friend, and I come from the same mold he comes from. it’s been a hard shuffle with me as a man, and as a black man. He’s not here with us anymore physically, but he’s in my mind and heart. Because what I strive to do now is all I can, while I can, and I won’t regret what I did not do. And I think that’s the statement Little Richard was trying to make – and that’s his true legacy.