As a child, Anna Malaika Tubbs looked up to her mother, a lawyer who advocated for women’s rights both in the U.S. and abroad. She was instructed to always pay attention to the way women, especially mothers, were treated in the various places they lived throughout her adolescence. In trying to follow her mother’s footsteps, Tubbs has always been a staunch advocate for women and mothers. Indeed, one of Tubbs’ goals is to bring Black women’s stories, that she feels should have already been known, into the limelight so that others can become educated on these previous “hidden figures”.

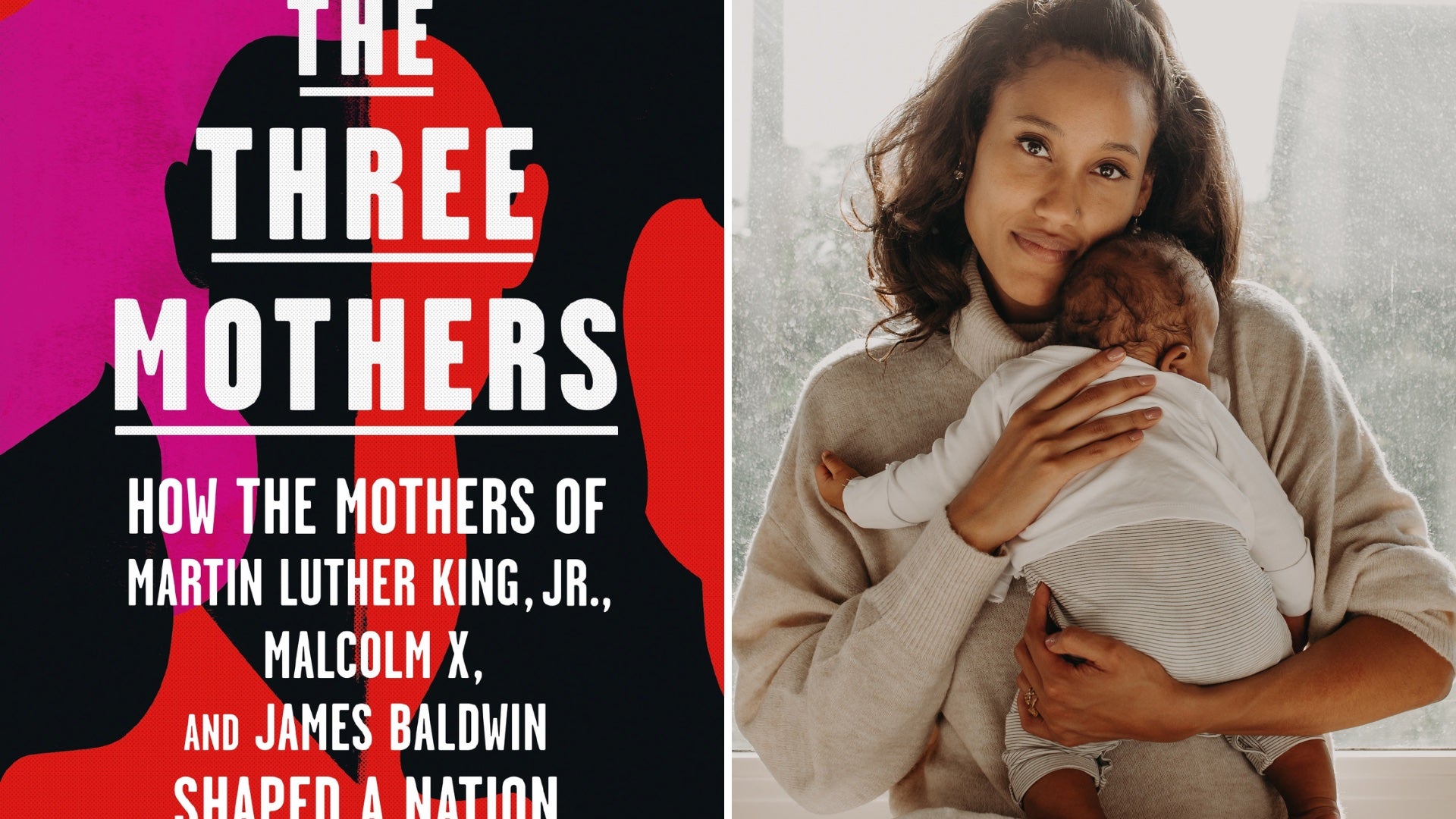

With this ethos in the back of her mind as a personal mantra, Tubbs has been constantly thinking about the power of motherhood, so much so that she authored her first book about three mothers born within five years of each other—who gave birth to their famous sons within a six-year time frame: The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr, Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation, which became a runaway New York Times Best Seller. The book delves into the complex stories of Alberta Williams King, Louise Little, and Emma Berdis Jones, as well as offers up a differing focal point of the civil rights movement from an oft-overlooked female perspective.

Just in time for the Mother’s Day holiday, Anna Tubbs sat down with ESSENCE to discuss her book and the importance of celebrating Black mothers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ESSENCE: Malcolm X said that “The most disrespected person in America is the Black woman.” Why do you think the role of Black mothers are so often overlooked?

In America, there’s so many things that play a role in terms of the patriarchy, and the intersection of racism and sexism, especially Black mothers, from the beginning of slavery in the United States. They’ve been treated as being less than human and were the only ones by law that were told we were the givers of non-lives, so that our children were property, they weren’t human beings. There’s a very complex relationship with the belief that Black women are not human, so there’s that erasure on a society level of our ability to even give life. But then we also see that play out in our own families where there is a silent belief that Black mothers are important, but we don’t acknowledge that, we don’t give them the spotlight, we don’t give them attention. We take those contributions for granted, and then we also see that play out in our lack of policy support, Black mothers especially. So, there’s many levels on which this is operating but it all comes from this intersection of both racism and sexism.

ESSENCE: How did becoming a mother change you and your perspective on life?

I was writing this book before I was a mother myself. Being in the middle of doing this research and finding myself expecting my firstborn, and then now being on the book tour still, and having a daughter as well, I approach things so differently because I feel the power of motherhood. I’m always talking about how important Alberta, Berdis, and Louise were to our world because they were erased. I’m very cautious of not being erased myself, so I approached my motherhood with a lot of confidence. I always think about it as something that is conventional, powerful, strong. I’m aware that there are all these systems that are trying to tell me differently or trying to rob that power from me, and it really allows me to approach the role very differently. But then I’m constantly thinking about how motherhood has further expanded my identity, my social activism, my work to hopefully create more equity in this world. My motherhood just brings me even more inspiration to add to that.

“A lot of us will say we thank our moms for being selfless, putting their needs behind everyone else’s and I want us to flip that.”

ESSENCE: Mother’s Day is coming up. Why do you think celebrating this holiday is so important within the Black community?

It’s critical because of the clear dehumanization of the Black mother, and when we’re fighting for our people on a daily basis, but we’re not paying attention to the ways in which Black mothers very uniquely have been dehumanized. We’re missing the point. This Mother’s Day, we need to celebrate, not just clap and put the spotlight on mothers, but translate that into actual protections for Black mothers, actual support for Black mothers. I’m very big on changing the narrative of thanking moms—a lot of us will say we thank our moms for being selfless, putting their needs behind everyone else’s and I want us to flip that. We thank our mothers for being our first leaders, our first caretakers, our first teachers, and especially our Black mothers who have told us that we can be what we want to be, even in a society that tells us not to dream, even in society that tells us not to believe in our worth and our dignity, but that our Black mothers have continued to tell us that we are worthy of being respected and treated just like everybody else, and really bringing this vision of what’s possible for our lives to the entire nation. Hopefully thank-yous can be much more appropriate and really fully encompass what Black mothers are accomplishing on a daily basis.

ESSENCE: What is your take on changing the narrative around being a “strong Black woman,” especially as it refers to Black mothers?

I am very opposed to anything that robs the humanity of Black women, any trope categorizing us or not acknowledging the fact that we are human beings. The “strong Black woman” trope is one of them. Truly, I believe that this notion that Black women somehow can withhold more pain than anyone else is wrong. The notion that we somehow are supposed to do everything all on our own and we don’t need anyone else to help us is also wrong. It’s not something that I believe we should necessarily allow other people to continue to put on us, “you’re such a strong black woman, you can do this on your own and you can handle more than everybody else.” We are holding that badge of honor, but I want the opposite, that we don’t have to do everything on our own, because there are other people who stand by us and who hold these burdens alongside us and we are no less than human and we are no more than human. We are just human beings, and that’s my opinion. Generally, I think that quite often, it is being perceived as a compliment. It is reifying the notion that we can somehow do more with less when we shouldn’t have to.

ESSENCE: Do you have any plans for a sequel or next book?

I do, I have another book coming that I’m working on right now. I have a novel that I’m working on and will hopefully start pitching this year, and then a nonfiction that is going to be announced. It’s going to be all about the patriarchy of the United States and how, for instance, the erasure of three Black women like in my first book is just one symptom of a larger system that is attempting to devalue the lives that are furthest away from being white, cisgendered men. I realized that so many people thought this was one separate incident that these three were erased and how shocking it was to them. I’ve kept telling people this isn’t actually shocking because this is how the system works. It’s not surprising that we didn’t know their names, but we should have. So the next book is all about how written into our laws, into our system, that we’re going to devalue certain lives is, and we don’t have to continue to spend time, telling women for instance, that they’re imagining things they’re feeling, when in reality, it’s the result of laws, it’s the results of policies that made it possible for their lives to be erased, as well as many other problems that happened, for Black women in particular.