Sunday was supposed to be the glorious wrap-up to the 2020 Olympic games in Tokyo. Gold medals should’ve been handed out in boxing, basketball, handball, rhythmic gymnastics, and track and field–with the storied marathon as the final event–culminating in the always-raucous closing ceremonies.

The pandemic robbed fans of the chance to watch stars like gymnast Simone Biles and swimmer Katie Ledecky, but also the chance to watch an unknown athlete (in say a new competition like say… sport climbing?) blossom before their eyes and becoming a household name in their own right. Legends like Carl Lewis, Michael Phelps, Cassius Clay, and the greatest American Olympian, especially given the political and racial realities of the times, Jesse Owens.

The four gold medals Owens—a Black man born to Alabama sharecroppers—won in the 1936 games, competing for a country that relegated him to second-class status once his spikes came off—sticking it to the Nazi propaganada machine with 110,000 Seig Heli-ing fans and a petulant Adolf Hitler in attendance–will never be equaled. Owens is the one who went down in the history books, but once again, given the political and racial realities of the times, his triumph is far from the whole story.

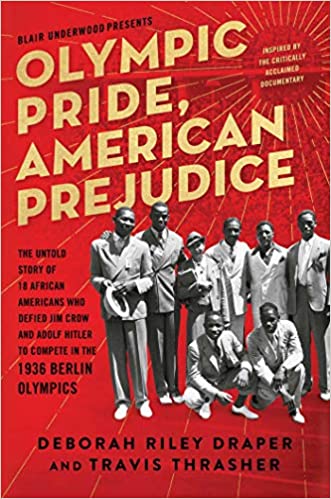

Filmmaker and author Deborah Riley Draper believes it’s high time to set the record straight through both her 2017 documentary, an NAACP Image Awards nominee, and her new expansive book Olympic Pride, American Prejudice: The Untold Story of 18 African-Americans who Defied Jim Crow and Adolf Hitler to Compete in the 1936 Berlin Olympics (Atria Books).

Draper was working on a story about Valaida Snow, an African-American jazz musician who was performing in Europe and imprisoned by Nazis in Copenhagen. She came across an article mentioning the other seventeen Black athletes in Berlin. It was the first time she’d learned of the large coterie of African-American jocks, nine of whom medaled, and a few who got screwed over (along with Jewish track and field teammates) by their own White coaches placating Germany’s fascist dictator.

“After reading that first article acknowledging Jesse Owens’s teammates of color, I was curious about who else was a part of this Black athletic cohort competing under the gaze of Hitler,” says Draper, who also directed the fashionista-centric Versailles ‘73. “Of course, mainstream media pushed a dominant narrative, which did not celebrate the intelligence, skill and ability of Black people, instead focusing on the exceptional ‘one’ instead of the exceptional many. A single exceptional Black man is an anomaly, many exceptional Black men and women clearly disproves the theory of Negro inferiority that underpinned race science, Jim Crow laws, and institutional racism and discrimination.”

The sixteen men and two women on the 1936 team triggered a seminal moment in the fight for equality. On the steamship from New York City to Germany, the teammates experienced a level of individual freedom unimaginable just days before, while also still not having the same privileged access like white their counterparts. While in Berlin, the absolute steely-determinism to reach the medal stand from sprinters Ralph Metcalfe and Mack Robinson (Jackie’s older brother, natch), the high jumper duo of Cornelius Johnson and David Albritton, and pugilist Jack Wilson to name a few astounds, which is why the African-American athletes were so popular in Berlin. However, defying the Third Reich on behalf of the Red, White, and Blue didn’t mean much back in their segregated home. The four golds, four silvers, and two bronzes won by Black athletes other than Owens were relegated to the dustbin of history, even though some of them served in World War II, like 400-meter champion Archie Williams of the Tuskegee Airman.

Draper has a special affection for the two women on the team, runners Louise Stokes of Massachusetts and Tidye Pickett of Chicago, who also faced the overt sexism of the times. Both women qualified for the 1932 Olympic 4-X-100 relay team, but were replaced by White runners at the last minute. In Berlin, Pickett competed in the 80-m hurdles, but she crashed in the semi-finals, breaking her ankle in the process. Stokes never got the chance to participate in the Olympiad.

Draper spent time with Stoke’s son and Pickett’s daughters, who had never seen footage of their mother representing the country that didn’t love her back.

“Two Black women marched into the Nazi Stadium, their presence a message and a clear demonstration of activism and Black feminism as we examine it through a current lens and in hindsight. They were pioneers in sport, forty years before Title IX,” says Draper. “Every time I look at the opening ceremony footage, where they walk past Adolf Hitler, I cry.”

Hear filmmaker and author Deborah Riley Draper discuss Olympic Pride, American Prejudice, on Tuesday, August 11 at 7:30pm EST on Squawkin’ Sports, presented by Brooklyn’s great Greenlight Bookstore.