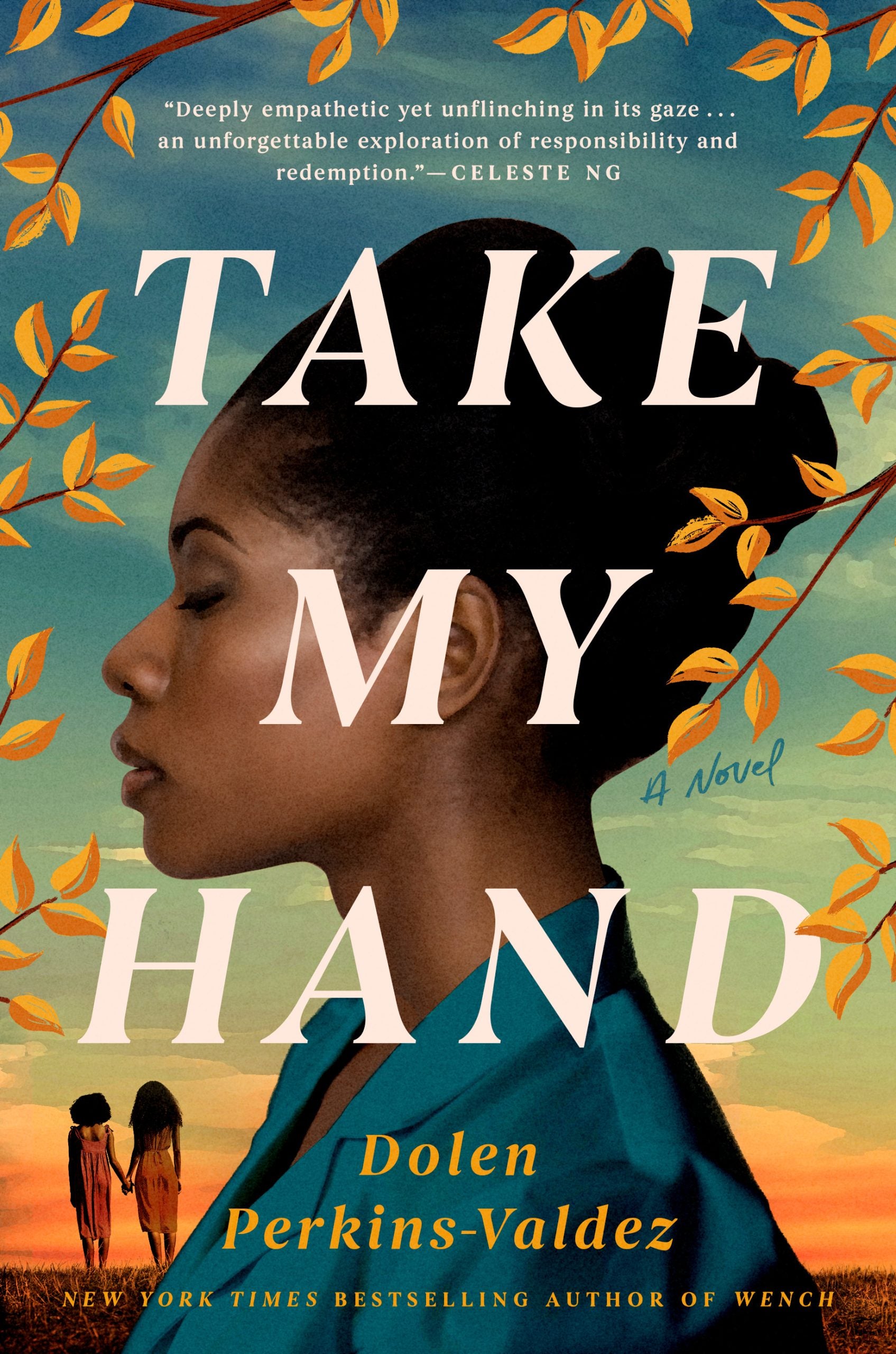

In the New York Times bestselling historical fiction novel Take My Hand, professor Dolen Perkins-Valdez, author of the acclaimed books Wench and Balm, offers a warm, yet honest welcome to revisit an achingly familiar moment in America’s past when Black female bodies weren’t protected.

When Civil Townsend, a nurse and recent Tuskegee University graduate takes a job at a family planning clinic, she soon discovers that two of her patients India, 11, and Erica, 13 are getting the Depo-Provera shot. Yet, one had not even received her first menstrual cycle, nor had they been intimate with anyone. As Civil begins to do more research with the help of the head librarian at Tuskegee University, Miss Pope, she soon begins to ponder the government and medical researchers motives and intentions for providing these family planning services, especially in poor, Black communities.

Civil ponders, “It was entirely possible the federal government was using our patients as if they were the subjects of a live clinical trial, the same thing they’d done to those men at Tuskegee. If the drugs were dangerous, it could be years before we knew if they’d caused cancer. By then it would be too late to connect their illness to Depo. They’d be too old or maybe even dead. Could we trust the government?”

The Tuskegee Syphilis project, the phrase Mississippi Appendectomy, systemic oppression of the poor and marginalized, involuntary sterilization, abortion, the legacy of historically Black colleges and universities, and the ill regard for the Black body are all themes that run deep in Take My Hand. Prior to the reversal of Roe v. Wade, ESSENCE had the opportunity to speak with Perkins-Valdez about the timeliness of Take My Hand and the parallels that exist in American society today.

You have a calling to bring others back to remembrance. With Wench, Balm, and now Take My Hand, you invite readers to step into the past.Can you share how the inspiration to write historical fiction books came into your life?

Perkins-Valdez: I’ve only recently realized that the first source of my inspiration to remember is my birthplace, Memphis, TN. It’s a city soaked in history, and I grew up in the arms of a rich Black community that told stories. When I began this journey, I didn’t know historical fiction would become my life’s work. I just wanted to write. Over the years, I kept getting pulled back into the archives. The voices of the past kept calling me, and to this day, I hope that I can do those spirits justice. I know that sounds odd, but I really do believe in the ancestral spirit world.

America has a legacy of having a complicated relationship with the Black body. What was the inspiration for Take My Hand and what was the research process like?

Perkins-Valdez: I highly recommend Harriet Washington’s Medical Apartheid as a source of the history of medical racism in this country. For anyone who is stunned by what happens in my book, Washington will contextualize the problematic history of experimentation on the Black body. I also recommend Killing the Black Body by Dorothy Roberts. I am deeply indebted to the work of Black women scholars who have delved into these histories and inspired my work.

Take My Hand couldn’t be more timely given the conversations around abortion being had in this country. Yet, the characters and plot of the story lend themselves towards diplomacy. How important was it for you to present these narratives in this way?

Perkins-Valdez: Civil rights struggles in this country have always incorporated both violence and diplomacy, and everything in between. It was the brilliance of the Movement–how to utilize all the strategies available to us to attain our goals. I didn’t consciously choose diplomacy here as much as I understood that the legal system was one means through which we worked. As I wrote this book, I was forced to acknowledge that with all the gains of the 1960s, there was still so much more work to be done in the 1970s.

Many historically Black towns that carry clues to this country’s past are mentioned throughout Take My Hand, especially Tuskegee, Alabama. Can you speak to why it’s important for this current generation to research the details of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study?

Perkins-Valdez: It’s now been 25 years since the highly successful TV movie Miss Evers’ Boys starring Alfre Woodard appeared. At the time, the film did a lot to raise awareness of this historical case. I wonder if the current generation knows about it, though. It’s important that we keep teaching these histories so they are not lost. My daddy graduated from Tuskegee in the late 1960s, and I’ve always felt connected to the history of that university. It is such a beautiful campus and the university has educated generations of families like mine.

Fannie Lou Hamer and the Mississippi Appendectomy are referenced in Take My Hand. Can you share what that term means, and how it came to be?

Perkins-Valdez: At one point I thought about titling the book Mississippi Appendectomy because the term has always fascinated me. Fannie Lou Hamer was so sharp and insightful. She was an audacious Black woman from Mississippi who was a legendary civil rights activist and even ran for the U.S. Senate in 1964. But many people do not realize that Hamer was subjected to a hysterectomy without her consent while she was undergoing surgery to remove a uterine tumor. In 1964, Hamer told a newspaper that she believed about “6 out of 10 Negro women that go to the hospital are sterilized with the tubes tied” at the North Carolina Hospital in Mississippi. Unfortunately, it was a common occurrence, and Hamer refused to be quiet about it.

In the book, Ms. Pope serves as the generous gatekeeper so many young scholars desire in this generation. Can you speak to the importance of transferring history from one generation to the next?

Perkins-Valdez: This is such a great question because the structure of the book is framed around Civil telling her daughter this story. And in my mind, her daughter is the reader. I am not necessarily sharing with a younger generation, but I am sharing with a generation of readers. Often Black elders thought they were protecting us when they did not share their stories. In a way, they were protecting us. I try not to transfer my own pain of racism to my children who are blissfully unaware of some of the more insidious incidents that might occur. They deserve their own innocence and experiences. Having said that, there were some things we needed to know. There were some narratives greater than any one individual’s experience that spoke to larger forces and struggles. In those instances, the elders must share. Otherwise, it will continue happening.

I loved Miss Pope because she’s a woman of faith who also lived a non-traditional life for the time period. She traveled the country with a female friend, had her own car, was liberated and balanced. What does this character represent for you? What is your hope that readers, and quite possibly the church, can learn from Miss Pope?

Perkins-Valdez: One of the things I love about Miss Pope is that she is a powerful woman of faith as well as a woman of conscience. These kinds of women have always existed in the church, but they had to be quiet about it because the Black church has historically been led by men. While the church had to publicly preach abstinence, we all know that certain things still happened and the women of the church were often the ones to have to deal with it. Miss Pope is a woman of her time–the students must maintain order in her library and she celebrates their rise into respectable jobs. Her motto is “eat first, then march.” But she is also a woman ahead of her time in that she makes certain unorthodox choices for herself and she feels no regret about that. I love her character, and I would have been one of those students hanging around the library just so I could get to know her.

Learn more about author Dolen Perkins-Valdez here.