When you think of Black cinema in the ’70s, images of XL afros, platform shoes, big guns and even bigger personalities likely come to mind. But beyond the legacy of fun catchphrases and iconic imagery, the Black films of this era had an impact on Hollywood that leave ripple effects to this day.

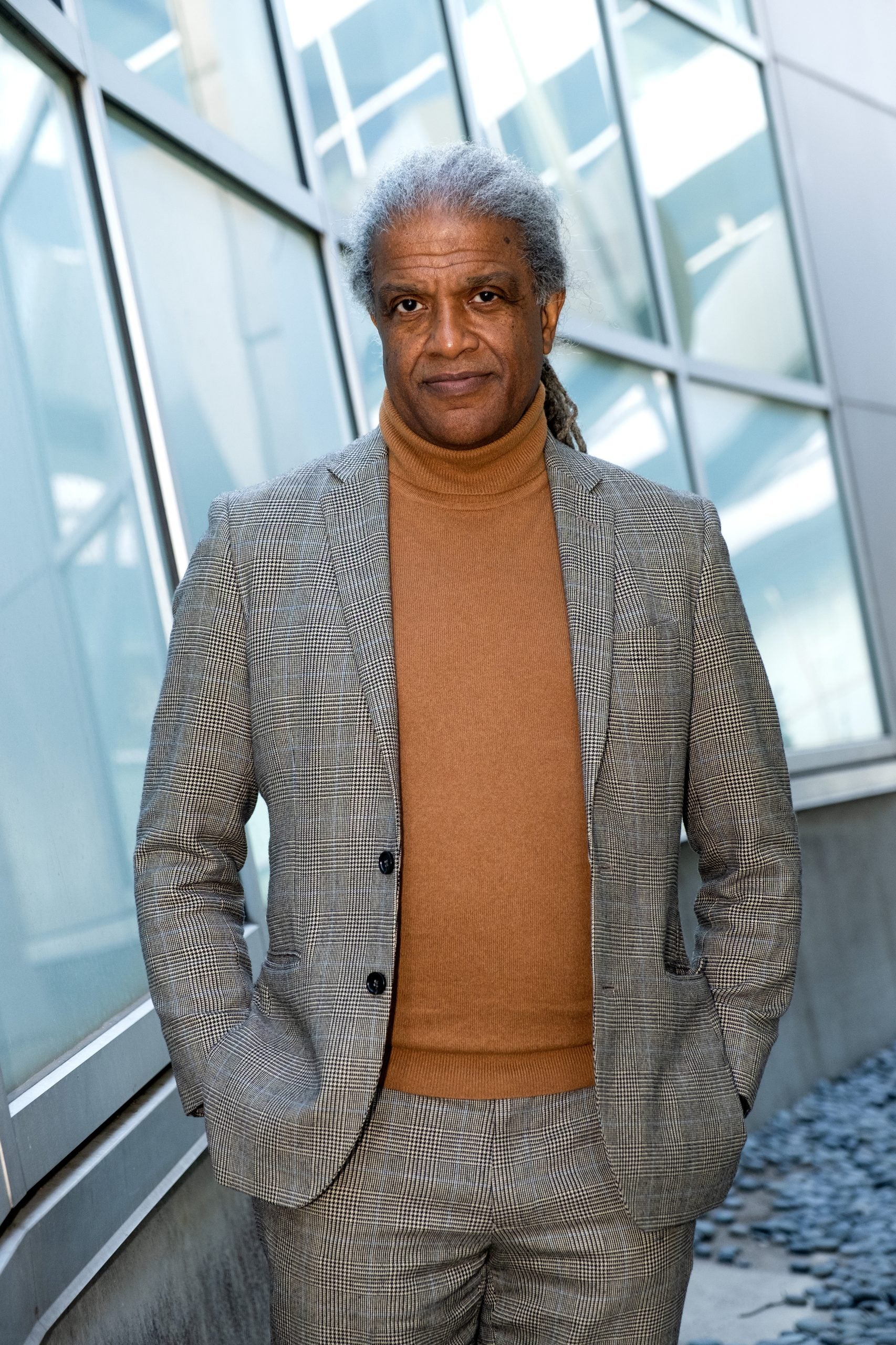

In steps film critic and historian Elvis Mitchell, with his new documentary film Is That Black Enough For You?, premiering on Netflix on November 11. Featuring archival BTS footage, film clips, and testimonials from actors from Zendaya and Samuel L. Jackson, to Whoopi Goldberg and Laurence Fishburne, the film pulls back the curtain on the full impact of the films of the late ’60s to early ‘7os.

With extensive film knowledge, decades of determination, and pivotal allyship from Hollywood legends, Williams was able to bring this eye-opening and entertaining tale of how the work of Black creators in front of and behind the camera, especially in the years from 1968 – 1978, changed all of Hollywood forever. ESSENCE spoke exclusively with the director/narrator about his take on this pivotal time period in film history and what modern audiences can learn about this overlooked piece of the Hollywood canon.

You delve deeply into Black film history on this project, but focus particularly on the movies produced from the late 1960s to the late 1970s. What do you feel is the significance of the films of this time frame for Black audiences?

WILLIAMS: I think for people at large, it’s certainly an important part of Black History that I think hasn’t been dealt with in this way. I wanted to look at it in a bigger way than just Blaxploitation – which is the way this decade has always been described – to instead look at the important films and cultural shifts that these movies caused. And there are so many. For the most part, when these movies are [discussed], they’re kind of dealt with in dismissive terms.

Agreed. You’re highlighting Black films in a way that is typically reserved for Martin Scorsese or Steven Spielberg films of the time. What do you think this adds to the canon for a generation who may be unaware of the impact and artistic value these films held and still hold?

WILLIAMS: I’m glad you brought that up because much of the documentation about this era is about those films that certainly were important, but also leave out these films that were this kind of defacto cultural movement and underground economy – well, not even underground. Many of these were incredibly big commercial successes that were responsible for financing the films of people such as Martin Scorsese and Robert Altman, who weren’t making many commercial successes in that time period.

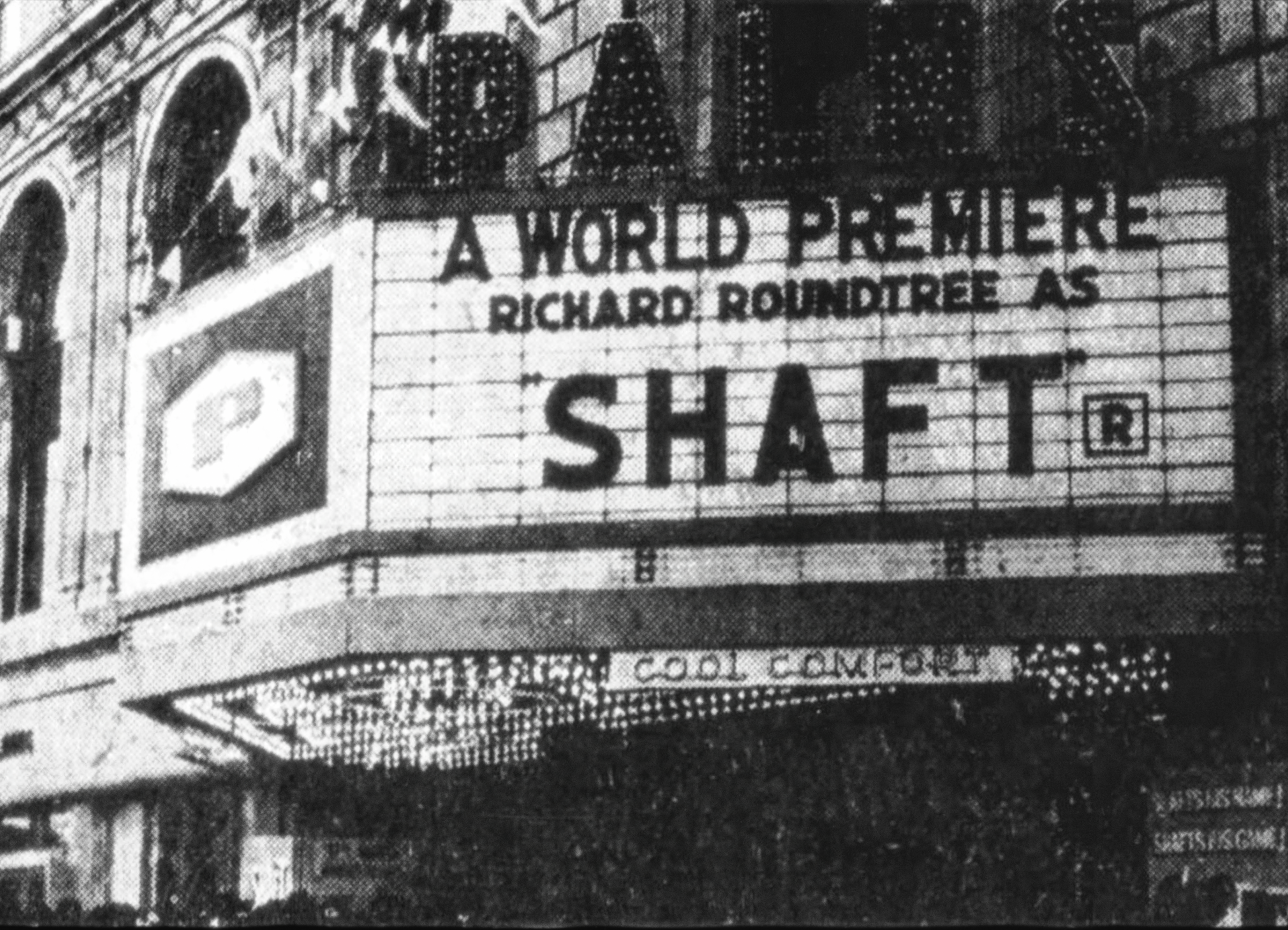

John Calley, who ran Warner Brothers in the 1970s and then was the CEO of Sony Pictures in the early 2000s, said to me that the dirty little secret of American cinema is that Black movies financed much of the mainstream. All we have to do is remember the example of MGM being saved from bankruptcy by the release of Shaft. And, that’s not the only case. Cleopatra Jones was a huge success, Coffy, many of these films.

Do you feel the term “Blaxploitation” is a dismissive categorization for films like these?

WILLIAMS: I don’t really have any issues with [the label], but it’s just one spoke in the wheel of the kinds of Black films being made in that period. And generally, when people say that, it’s a way of sort of saying, “these movies were intentionally campy or silly,” which wasn’t the case. I think a lot of this is a reaction to the size of the personalities in the movies. Maybe a lot of them weren’t particularly well staged. There was a lot of ambition and talent in front of the camera that was finding its own way. And these movies were incredibly successful.

But we also had Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, or Killer of Sheep, or Watermelon Man, or Lady Sings the Blues, or Sounder, or Claudine, all of

which were Oscar nominees in the year 1972, which was such a big year for

African Americans in the Oscars. It never gets talked about in that way.

It just becomes convenient, and it becomes a way of cramming all this stuff into the same box in the same way, that so often I’ve said that even Black film itself becomes its own genre. People tend to not separate out a Black

comedy or a Black romantic melodrama, or a Black western, though there are not many of them. They’re all just ‘Black film.’

You’ve been trying to make this project come to fruition in one way or another for the better part of the last two decades. Why were you finally able to tell this story now?

WILLIAMS: Well, it really started to come into its own to happen about four years ago when I was talking to Steven Soderbergh, and as I’ve mentioned before, he said to me, “Well, so, what exactly is it you’re doing with your career anyway?” And I said, “That’s sweet that you think I have a career. And I’ve been trying to make this project in one way or another for a long time.” And he said, “Well, let’s just go ahead and do it.” That was that. Just to give it some exponential, he brought in David Fincher, who, by the way, just said at one point, “Oh, I know why you couldn’t get this done. It’s about a bunch of Black people. Well, let’s go do it.”

That kind of support was really what it took to free this project from

inertia and keep it moving to its final resting place, which is on Netflix on November 11th. [For years] I would tell people about it, and people would respond and think it sounded interesting, but it wouldn’t go anywhere. And I couldn’t get it published as a book. It was Soderbergh really seeing the value in it and saying, “I want to see this on the screen. Let’s go ahead and make it. This is an important part of film history.”

What is the takeaway from this story? How do you hope learning this untold perspective of film history will reframe American cinema for audiences?

WILLIAMS: I think we tend to forget that every decade or so Black film is treated as if it had gone away and has to be accorded this big notice and big return. And I think we have to avoid that danger of doing that kind of thing, of saying that Black film needs to be treated as if it’s “come back” because it never goes anywhere. It’s just that people lose interest in covering it and dealing with it as this ongoing cultural phenomenon that has to go away like anything else.

That’s what I’m hoping people start to do – not just looking at this as Black

film, but talking about these films within their own genres and what they

achieve or fail rather than just trying to lump everything together. Because once you do that, then you give people an easy way to sweep it into the closet and close the door on it, and I don’t want to see that happen again. And I’m betting you don’t either.